The northernmost land action of the American Civil War did not occur during the Confederacy’s twice ill-fated invasions of the north but rather happened in the small city of St. Albans, Vermont, less than twenty miles from the Canadian border. Perpetrated by a small band of Confederate raiders, this was more reminiscent of a wild west style attack than a tactical cavalry raid.

Brian Hughes explains.

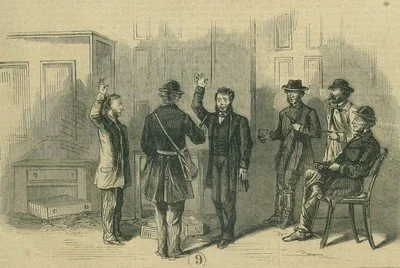

A woodcut illustration of the St. Albans Raid. In the image, at the bank, the raiders forced those present to take an oath to the Confederacy.

Introduction

As 1864 was coming to an end the outlook for the Confederacy appeared bleak. The south was under relentless Union pressure from east and west, on land and at sea. In Georgia, General Sherman was leaving a path of destruction in his wake and had captured Atlanta, the second most important city in the South. Simultaneously in Virginia, General Robert E. Lee was endlessly preoccupied with attempting to stymie Ulysses S. Grant during the Peninsula Campaign, inflicting heavy casualties in cataclysmic battles but unable to effectively achieve any substantial strategic objective. Union forces were also devastating the Shenandoah Valley and tightening the noose around the south with their naval blockade.

The increasing demoralization of southern troops and populace manifested itself politically. Becoming increasingly distressed, certain figures began to think outside the box for solutions, even if they were only short term. Twenty one year old Kentuckian and Confederate soldier Bennet H. Young came forth with an unorthodox yet bold proposal. Having taken part in several battles in and around the Midwest, Young had fled a Union prison camp where reaching Canada and returning home via a Confederate blockade runner operating out of Halifax. Young believed he could mount a series of forays into the meagerly defended northern New England states from Canada. Despite the small scale nature of the raids, any amount of fiscal gains would be sufficient to assist the cash strapped Confederate government and act as a sort of monetary life support, extending the conflict just long enough until a more ideal political outcome could be agreed upon for the Confederacy. Similarly, Confederate operations in the far north could potentially divert Union troops away from more active fronts, relieving pressure on the hard pressed farms and plantations necessary to sustain the southern war effort.

Canada

Although officially neutral in the conflict, Canada, then still a disunited British colony, harbored great sympathy for the Confederate cause. Heavily reliant on southern cotton and historic enmity with neighboring states (mainly New England) contributed to these sentiments. A multitude of Confederate agents, spies, and fundraisers would operate out of cities such as Montreal and St. Johns some of which were aware of the tactical potential Canada offered geographically. Young made extensive use of these contacts which he garnered throughout his time there.

Why St. Albans

St. Albans was selected for a variety of reasons. Located a mere fifteen miles from the border with Canada, St. Albans was home to several banks. The city was easily accessible with several roads leading in and out of the downtown area, being just close enough to Vermont’s largest city, Burlington. In addition, the town was meagerly defended with no substantial military force in and around the region.

Raid, October 19th, 1864

The original date of the operation was scheduled for the 18th of October, but the Franklin County Farmers Market thwarted these plans with the increase in population and presence of authorities. Delaying the attack by a day or two would similarly ensure the banks were more laden with money following market day.

Young had about twenty men at his disposal, which he split up in subunits of five or six each tasked with striking one of three banks. The raiders dressed in plain civilian clothes and initially disguised their southern accents upon making entry into the city for the purpose of reconnaissance. At around three pm, Young stood on the steps of local hotel unsheathed his pistol and with great braggadocio exclaimed “This city is now in the possession of the Confederate States of America!” This was the signal for the attack as the Confederate operatives sprung forth and furiously rode through the streets toward their objectives.

Their three targets were the St. Albans Bank, The Franklin County Bank, and First National Bank were all situated within a block and a half of one another. The rebels took the locals by complete surprise and quickly rampaged through the three banks, robbing them and forcing civilians with their arms raised to “solemnly swear to obey and respect the Constitution of the Confederate States of America.” Treasury notes and bonds were taken in addition to cash, but the banks were intentionally not thoroughly looted the banks of all their contents given the necessity of the rebels to flee the city swiftly.

Some of the southern raiders took advantage of the ensuing pandemonium to steal horses to better facilitate their escape. The raid was over in less than half an hour but not before the southerners shot one local civilian, Elinus Morrison, mortally wounding him. Morrison attempted to confront the raiders who then shot him in the abdomen. One Southern raider had been wounded during the flight as the Confederates unsuccessfully tried to set fire to the town.

Pursuit

The perpetrators set off with stolen horses in addition to their loot from the banks, this incumbered them slightly. A Union army veteran and St. Albans resident Captain George Conger rapidly organized a posse and gave chase. The Confederates again attempted to light fire to several bridges to better ensure their escape but once again the flames were quickly doused by the pursuers. Eventually the marauders parted in to separate groups and continued, northward, Vermont authorities alerted their counter parts in Canada hoping they would apprehend the intruders. The Canadian authorities decided to cooperate with the Vermonters, capturing a handful of the raiders once across the border, they quickly confiscating their weapons and cash, and called on the militia to further patrol the border. The Canadians confiscated eighty seven thousand dollars in money, roughly equivalent to two million in today’s currency. By wars end in April 1865 the banks of St. Albans had been reimbursed and the remaining captives released.

The St. Albans raid was a revealing act of Confederate desperation in the war’s final months. Though militarily insignificant, it displayed how far the southern operatives were willing to go-violating borders and testing neutrality. The raid temporarily shocked the north and exposed geographical vulnerabilities. In the end the raid failed to divert significant resources, thus ensuring the Confederacy’s inevitable collapse.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.