Megasthenes, (Μεγασθένης), remains one of the most fascinating bridges between the classical Mediterranean world and early Imperial India: a Greek diplomat, ethnographer and writer who, as ambassador of Seleucus I Nicator, lived at the Mauryan court of Chandragupta and composed what became the first sustained Western account of the subcontinent. Exact details of his birth and upbringing are slim; later sources and modern scholars conventionally place his life in the fourth–third centuries BCE (often cited as born c. 350 BCE and dying c. 290 BCE), and describe him as an Ionian Greek who had served in the eastern satrapies before being dispatched to Pataliputra (modern Patna) in the decades after Alexander's campaigns.

Terry Bailey explains.

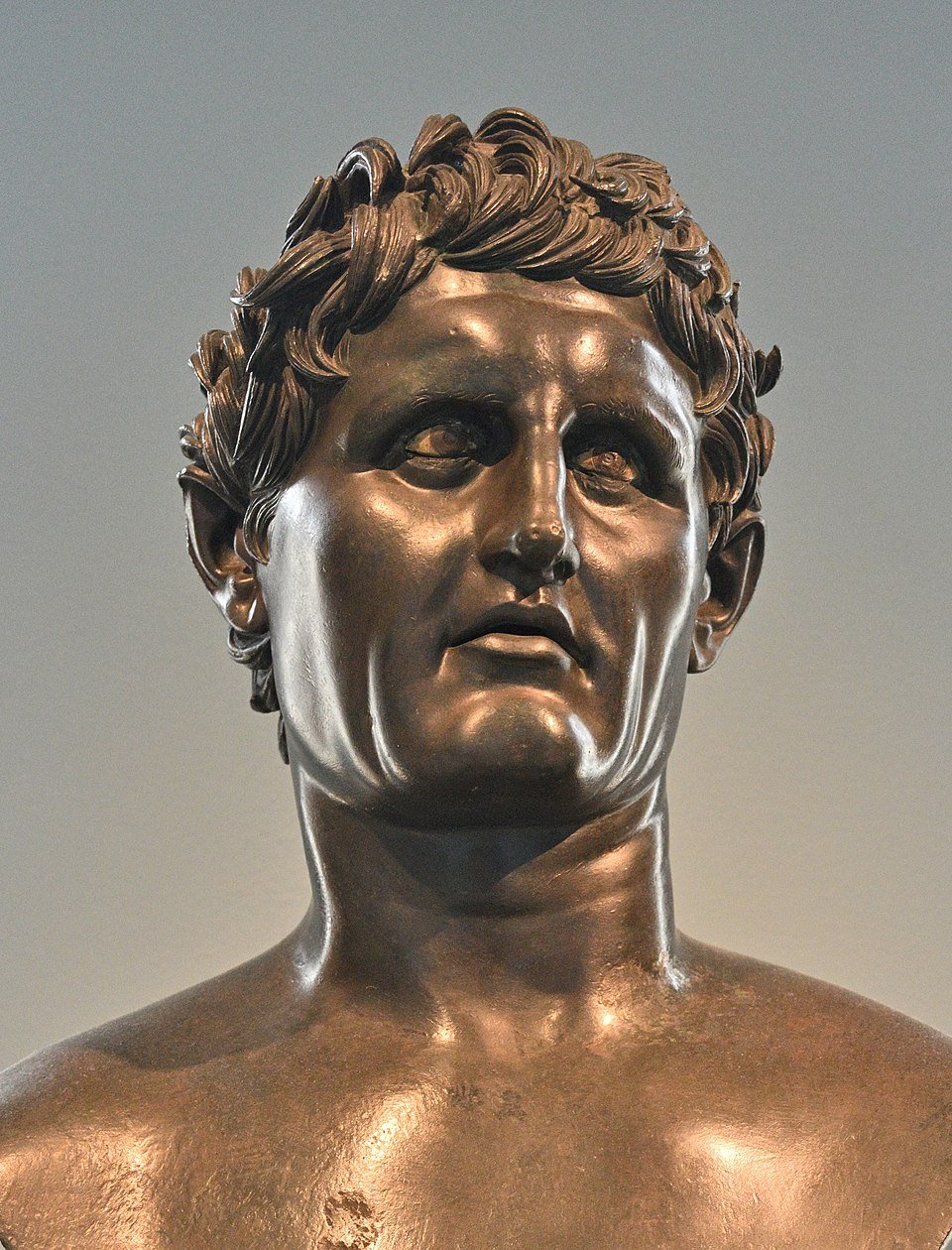

A Bust of Seleukos I Nikator, Bronze, Roman, 100BCE-100CE at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale Naples AN 5590. Source: Allan Gluck, available here.

Megasthenes' embassy must be read against the turbulent political map that emerged after Alexander: in the 320s–300s BCE the Macedonian successor states and the rising Mauryan power negotiated borders, alliances and exchanges. Seleucus I, having consolidated power in the west and east, sent envoys to the new Mauryan ruler; Megasthenes is usually identified as the Greek who represented Seleucus at Chandragupta's court, sometime around the opening years of the third century BCE (classical accounts often place the mission in or near 302–300 BCE). While Greek authors disagree about details and chronology, there is broad agreement that Megasthenes lived for a period in Pataliputra and had access to court circles and local informants.

What secured Megasthenes' long-term reputation was his written work, the Indica (Greek: Ἰνδικά) — a multi-book description of India that combined geography, ethnography, political organization, natural history and curious anecdotes. The original Indica is lost, but substantial fragments and paraphrases survive embedded in later authors such as Arrian, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus and Pliny; from those citations, scholars have been able to reconstruct large portions of his themes and claims. His account ranged from pragmatic observations, fortified layout and wooden palisades of the Mauryan capital, the scale of rivers such as the Ganges, commercial products, and administrative practices, to more exotic reports (stories of ancient invaders rendered as Dionysus or Heracles, fabulous creatures, and social arrangements unfamiliar to Greeks). The composite picture is of a careful observer who also relied on local informants and existing oral traditions, which accounts for a mix of reliable detail and mythic accretion.

Scholars and ancient critics have long debated how much of Megasthenes to trust. Arrian, the second-century CE historian who quotes Megasthenes sympathetically, treats him as an important firsthand source; by contrast, Strabo and Pliny accuse him of exaggeration and fantastical reporting. Modern historians tend to take a middle way: many of Megasthenes' topographical and administrative notes, the scale of Pataliputra, references to markets and ports, the prominence of philosophers in court life, and certain demographic or economic observations, find independent support or at least plausibility, even when his mythic or secondhand claims require skepticism. In short, Indica is invaluable as the earliest sustained ethnographic encounter between Greece and India, but it must be handled critically and compared with other evidence.

One important way Megasthenes' descriptions have been tested is by archaeological work at the site he called Palibothra (Pataliputra). Excavations in the Patna region, notably at Kumhrar, Bulandi Bagh and other spots have revealed extensive Mauryan-age remains: large wooden palisade foundations, signs of monumental timber architecture, and evidence for an unusually large and administratively complex urban center in the third century BCE. Those discoveries do not prove every specific claim in Indica, but they corroborate the broad outline of a heavily fortified, sprawling Mauryan capital whose scale and administrative character impressed foreign visitors. When combined with indigenous literary references (Buddhist and Jain texts that mention Pataliputra) the archaeological record strengthens the view that Megasthenes recorded real, observable features of Mauryan urban life.

Beyond topography and economy, Megasthenes' notes on society, his listing of social groups (sometimes translated later as "seven castes" or "classes"), his statements about the role of philosophers and the presence or absence of slavery, and his remarks about trade routes and commodities have been influential (and controversial) in modern reconstructions of early Indian institutions. Some of these formulations reflect Greek categories forcing themselves onto Indian realities; others appear to preserve local administrative distinctions that match evidence from inscriptions and later Indian sources. Thus Indica functions simultaneously as an ethnographic snapshot shaped by cross-cultural translation and as a repository of useful data that historians weigh against Indian textual traditions and material finds.

The Indica's afterlife in the classical tradition is also part of Megasthenes' achievement: later geographers and historians in the Greco-Roman world even when skeptical used his material as the baseline for European knowledge of India well into late antiquity. That transmission made Megasthenes an intellectual conduit: Mediterranean readers learned about Indian rivers, cities, products, and philosophical schools primarily through his fragments and their later epitomes. At the same time, the fragmentary preservation of Indica has posed chronic editorial problems: nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars produced reconstructions and critical editions, but disagreements persist about which quoted passages genuinely derive from Megasthenes and which were later interpolations.

What we know of Megasthenes' later life is sparse. Classical compilations usually report that he died around 290 BCE and they place his productive period, the embassy and the composition of Indica in the early third century BCE, after which his text circulated among Greek writers. There are no surviving personal letters or an archaeological "archive" that preserves Megasthenes' own voice beyond the Indica fragments; his passport into history is therefore the composite testimony of those later authors and the material traces of the Mauryan world that those fragments describe. Modern scholarship treats him as an essential, if imperfect, eyewitness: a man whose curiosity and court access opened up India to the Mediterranean imagination and whose mixed reliability reminds us how every cross-cultural encounter is a dialogue between observation, report, and interpretation.

In the end Megasthenes matters less as a flawless chronicler than as the first sustained Greek interlocutor to try to comprehend and describe a large part of the Indian subcontinent for a foreign audience. His Indica remains a foundational text for reconstructing Mauryan urbanism, trade networks and aspects of social organization; the archaeology of Pataliputra and the mirrors of indigenous literary traditions have validated many of his broad claims while also exposing the limits of any single ancient eyewitness. For historians of cross-cultural contact, Megasthenes is therefore indispensable: not because every line is true, but because his mixture of careful description, secondhand story and interpretive framing is exactly the kind of source that, when read critically, can illuminate how two great ancient worlds first began to see one another.

Megasthenes' legacy endures because his work represents one of the earliest and most ambitious attempts to translate an unfamiliar civilization into terms accessible to his own. Although filtered through the perceptions of a Greek diplomat shaped by the political tensions and intellectual categories of the Hellenistic world, the Indica remains the earliest extended window onto Mauryan India as viewed by an outsider who sought, however imperfectly, to observe rather than simply imagine. The survival of his account only in fragments and paraphrases has inevitably obscured parts of his original vision, yet what remains is striking in its breadth: geography, economy, administration, philosophy and the daily rhythms of a thriving imperial capital all find a place in Megasthenes' narrative.

Taken together with archaeological discoveries at Pataliputra and the testimony of Buddhist and Jain traditions, his observations gain depth and credibility, allowing modern historians to reconstruct with greater confidence the scale, sophistication and cosmopolitan nature of early Mauryan society. At the same time, the tensions within his work, the blend of sober description with mythic elements, and the temptation to map Greek concepts onto Indian realities serve as a reminder of the challenges inherent in any cross-cultural encounter. Megasthenes was neither a naïve recorder of wonders nor a wholly reliable scientific observer; instead, he was a pioneer navigating the uncertain ground between cultures, translating what he saw and heard into the intellectual language of his own world.

For that reason, Megasthenes stands as a crucial figure in the history of ancient knowledge. His Indica-shaped Greco-Roman conceptions of India for centuries, influenced later geographers and historians, and continues to serve today as an indispensable, if occasionally problematic—foundation for understanding the Mauryan Empire at its height. His work invites individuals to read critically, compare sources, and recognize the interpretive layers that accompany any ancient report. Yet it also invites admiration: for his curiosity, his willingness to engage deeply with a foreign court, and his attempt to make sense of a vibrant society undergoing rapid political and cultural transformation. Ultimately, Megasthenes' significance lies not only in the information he preserves, but in the very act of cultural translation he undertook, a reminder that the earliest bridges between civilizations were built as much by storytellers and observers as by diplomats and kings.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.