Major General Daniel Sickles was one of the most colorful and controversial figures of the Civil War era, known as much for his flamboyant personality and scandals as for his political and military actions. He can be viewed as either an American war hero or an infamous murderer and insubordinate military commander, and it's not easy to decide which categorization is more accurate. Sickles was an unscrupulous swindler who led a life that no writer of fiction could have invented. A brief synopsis: Lawyer, Tammany Hall politician, US Congressman from New York, he married a 15 year old woman and became a serial adulterer, brought an infamous prostitute to London to meet the Queen, murdered his wife’s lover (Francis Scott Key’s son Philip, the US District Attorney for the District of Columbia) in broad daylight across the street from the White House, pleaded temporary insanity (invented for him by Edwin Stanton) and won acquittal by smearing her in the press. And that was just before the war!

Then, he recruited the Excelsior Brigade, lost his leg at Gettysburg, testified against Meade at Congressional hearings, was appointed to evaluate the impact of occupation on the south, appointed diplomat to Colombia, had an affair with the Queen of Spain, received the Medal of Honor, and championed saving the battlefield at Gettysburg as a park.

In short, he was a diplomat, playboy, lousy husband, beloved general, congressman, murderer, and good old boy. This was a man who looked out for himself and got other people killed with no qualms. He had zero training as a soldier. He was self-aggrandizing, selfish, corrupt, and unprincipled, but he was also brave, patriotic, and extremely enterprising. He got away with all of it because he was colorful, resourceful, and charming. Thomas Keneally, the author of Schindler’s List, wrote an outstanding biography of General Sickles, entitled American Scoundrel, and that sobriquet fits perfectly.

Lloyd W Klein explains.

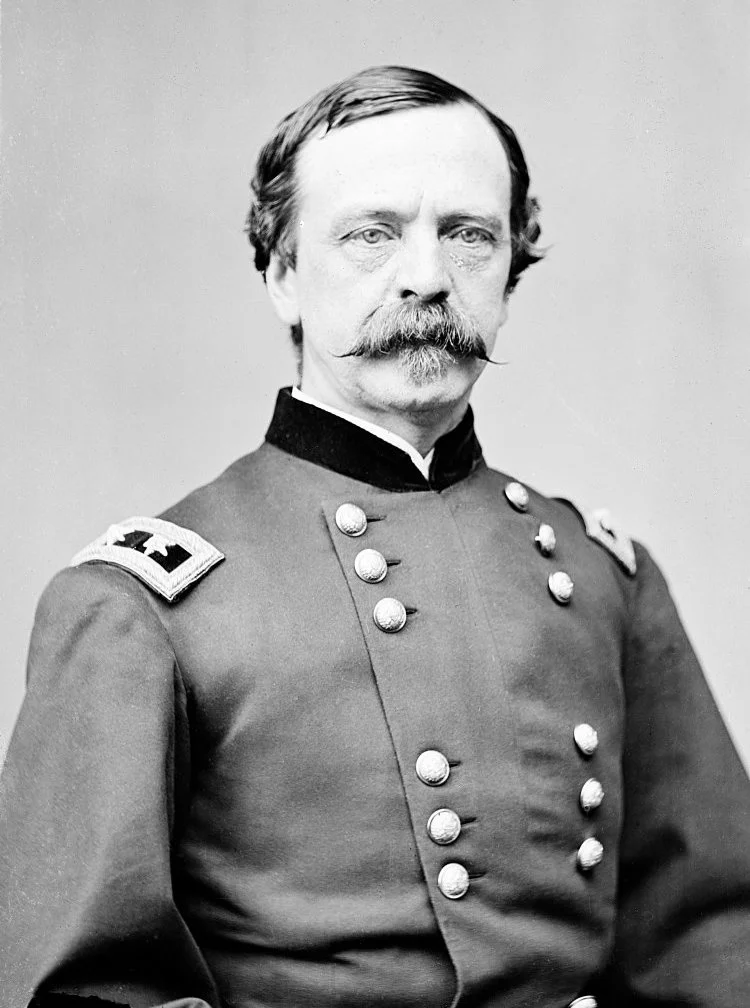

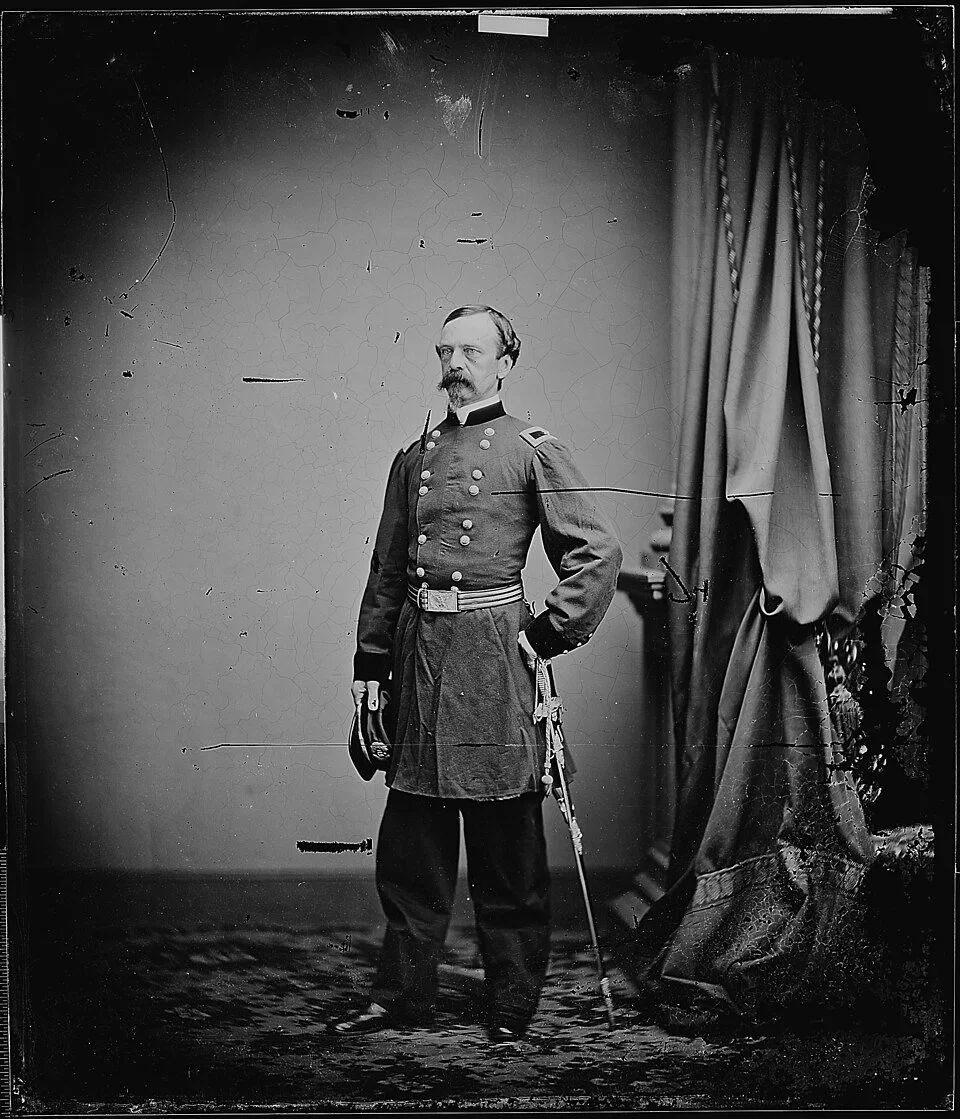

Major General Daniel Sickles.

Early Life

Sickles was born to a wealthy New York family and trained as a lawyer. He soon became involved in Democratic Party politics. He was closely aligned with the Tammany Hall political machine, which helped his rise despite his checkered personal life. He served in the New York State Senate and was then elected to the U.S. Congress as a Democrat from New York in 1856.

The Murder in Lafayette Square (1859)

Sickles discovered that his wife, Teresa, was having an affair with Philip Barton Key, the handsome U.S. Attorney and son of Francis Scott Key, author of The Star-Spangled Banner. Sickles shot and killed Key in broad daylight in Lafayette Park, across the street from the White House. This led to his greatest notoriety before the war. Key had been signaling Teresa with a white handkerchief outside her window to arrange secret meetings. When Sickles found out, he confronted Key in public, shouted, “You must die!”—and shot him multiple times with witnesses present.

The trial was sensational. Sickles’ defense team—including Edwin Stanton, future Lincoln war secretary—argued that Sickles was driven temporarily insane by betrayal. The public mostly sided with Sickles, seeing him as a wronged husband defending his honor, even though he himself had a long track record of infidelity. Verdict: Not guilty. Sickles was acquitted after arguing he was temporarily insane. Sickles' claim to Infamy is that he was the first person in U.S. history to use the temporary insanity defense—and it worked.

Despite his notoriety, Sickles was politically well-connected and knew his way around the intricacies of Congress and New York State politics. He was not a natural Lincoln ally. Lincoln, a Republican, ran against the very sort of people Sickles called friends. However, once the Civil War began, Sickles became a vocal pro-Union Democrat, which made him useful to Lincoln, who desperately needed Democratic support to prevent border states and northern cities from turning against the war.

Lincoln rewarded Sickles with a commission as a brigadier general, despite his scandalous past. He had no military experience, just political clout, becoming one of the few political generals. But Lincoln understood that having a Democrat representing New York and Tammany on his side was good politics..

Army Experience Before Chancellorsville

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Sickles used his connections to raise troops despite having no formal military training. Sickles organized the Excelsior Brigade (composed mostly of New York volunteers) and was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers in September 1861. He commanded with flair, although he had no prior military experience.

In early 1862, Sickles temporarily lost his commission due to political wrangling and issues with his official confirmation. He spent several months lobbying in Washington and was reinstated later in 1862, thanks to his political influence. Sickles commanded the Excelsior Brigade, a New York volunteer unit he had personally recruited and organized. The brigade was part of Major General Joseph Hooker’s division in III Corps under the command of Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman.

Seven Days

At the outset of the Peninsula Campaign in spring 1862, Sickles was not present with his brigade. He had returned to Washington, D.C., to lobby for confirmation of his military commission, which was being held up in the Senate due to concerns over his checkered past and political appointment. Sickles’ commission was finally confirmed in May 1862, and he rejoined the Army of the Potomac shortly before the Seven Days Battles. By the time of the actual fighting, his Excelsior Brigade had already seen action without him at battles such as Williamsburg and Fair Oaks/Seven Pines.

During the Seven Days Battles, Sickles’ brigade participated in some of the fighting, particularly in the Battle of Oak Grove (June 25) and Glendale (June 30), though the records are somewhat unclear on the exact extent of Sickles’ personal involvement.

By the end of 1862, Sickles was commanding a division in the III Corps, Army of the Potomac. He served under General Joseph Hooker and participated in the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 1862), although his division was held in reserve and saw limited action.

Chancellorsville (May 3-4, 1863)

By the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville, Sickles was a major general in command of the III Corps. He was a political general with limited battlefield experience but significant ambition and personal charisma.

On May 2, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson launched the famous flanking attack that shattered the Union XI Corps on the Union right. Jackson devised a daring plan that divided the numerically inferior southern army and then marched his Corps far around the Union army to strike unsuspecting northern troops on their extreme right flank. Meanwhile, Sickles, with the III Corps in the center-left, was ordered to make a probing advance and moved forward to Hazel Grove, a clearing with commanding artillery potential. We know today that numerous Union forces had detected Jackson’s movement, and Colonel Sharpe of the Military Intelligence Unit had warned Hooker. But Hooker believed that Jackson was in retreat, not advancing on his flank. Scouts on Hazel Grove from Sickles’ Corps informed Hooker that they saw and heard Jackson’s men to their west. Sharpe had even deployed aerial balloons and spotted the movement.

As the morning progressed though, Hooker grew to believe that Lee was withdrawing. He ordered III Corps to harass the tail end of Lee's "retreating" army. General Sickles advanced from Hazel Grove towards Catharine Furnace and attacked Jackson’s men in the rear guard. Jackson’s main force continued onto Brock Road, where it meets the Orange Plank Road, directly into the Union right flank. Sickles informed Hooker, to no avail, that Jackson wasn’t retreating but was on the move.

By the morning of May 3, Howard's XI Corps had been defeated, but the Army of the Potomac remained a potent force, and Reynolds's I Corps had arrived overnight, which replaced Howard's losses. About 76,000 Union men faced 43,000 Confederates at the Chancellorsville front. The two halves of Lee's army at Chancellorsville were separated by Sickles' III Corps, which occupied a strong position on high ground at Hazel Grove. Sickles’ troops at Hazel Grove were right in between. Hooker could have attacked either part and destroyed it. JEB Stuart was completely aware of this predicament. He was not in a position for a defensive battle. Instead, he prepared an attack at dawn on Hazel Grove rather than await what seemed to be the obvious move.

But Hooker ordered Sickles to withdraw from Hazel Grove and fall back closer to the main Union line—a serious tactical error. Hooker ordered Sickles off the high ground and instead to another area much lower called Fairview. Hooker felt he was losing and he couldn’t see the advantage of his position so he retreated to what he erroneously thought was a safe fallback position. JEB Stuart had been ready to fight for that ground, and now it had been given to him. Hazel Grove was then occupied by the Confederates, who used it to devastating effect. He took control of the high ground and blasted Sickles at Fairview, where he was a sitting duck for Stuart’s artillery.

Sickles would remember this moment 5 weeks later at the Peach Orchard. He wouldn’t make the mistake again of following orders he knew to be wrong, and especially he would not again let the high ground in his front be captured by the enemy without a fight.

Daniel Sickles, estimated to be 1861.

Gettysburg & the “Peach Orchard Gamble” (July 2, 1863)

Sickels’ most controversial moment came at the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), where he disobeyed orders and advanced his corps into a dangerously exposed position.

The move led to severe casualties but arguably disrupted the Confederate attack. On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Sickles did something extraordinary—and reckless. His orders were to hold the left flank of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. But Sickles disobeyed, moving his III Corps forward nearly a mile to a rise near the Peach Orchard, creating a salient (a bulge) in the line. The decision to abandon the line General Meade assigned him to defend between Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge, but rather to advance to the Peach Orchard, must count as one of the most fateful decisions of the entire war. General Sickles decided entirely on his own to defend the Sherfy Peach Orchard, adjacent to the Emmittsburg Pike, not the position assigned to him. This not only created a huge, undefendable salient, but it also left his flanks uncovered. The left flank, of course, was Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, and the Wheatfield. All of these killing fields had to be covered on the fly as troops entering the battle were immediately sent to desperate locations to save Sickles’ III Corps and the entire front. Day 2 of Gettysburg therefore depended on the heroism and courage of many men and their regiments now honored as heroes, including William Colville, Joshua Chamberlain, Patrick O’Rorke, and many others.

Sickles and his III Corps were assigned on the early morning of July 2 to be in line south of Cemetery Ridge and cover the low area and the Round Tops. Sickles perceived, correctly, that the ground his position was about 10 to 15 feet higher than the ground he was supposed to defend. He believed this ground would be perfect for artillery to destroy him. A very similar situation had happened at Chancellorsville when he was ordered by General Hooker to give up Hazel Crest, which then became the key to confederate artillery destroying the army on day 2 of that battle. Sickles hadn’t forgotten that experience, so he asked Meade for permission to move up at least twice. Meade thought that area was not a good position for artillery but was rather a no-man’s land, and on Day 3, he was proven to be correct. But Sickles made the decision to move up to the Sherfy Peach Orchard anyway. He showed his position to General Warren and to Captain Meade, the general’s son, neither of whom thought this was a good idea. Famously, when General Meade saw this right before the battle opened, he told Sickles that he was out of position and knew a disaster was in store.

III Corps was hammered by Confederate attacks. He was blasted in the leg by a cannonball (said to have kept smoking as he lay on the ground). His line collapsed, but his move arguably disrupted Longstreet’s attack and may have helped buy time for Union reinforcements. He lost his right leg, which had to be amputated, and sent the limb to the Army Medical Museum, where it’s still on display. Sickles visited it regularly in later years. He’d bring guests along, saying, “Let’s go see my leg.”

As Sickles recuperated, Lincoln visited him in the hospital. Sickles spun his wild maneuver as a kind of accidental genius: “Yes, I moved without orders, but look how it saved the Union line!” Lincoln, who knew politics as well as war, didn’t publicly criticize Sickles, even though most generals thought he’d nearly ruined the battle. Lincoln needed popular heroes, and Sickles was selling himself as one. There’s no record of Lincoln outright endorsing Sickles’ version of events—but he never denounced him, either. Lincoln tolerated Sickles because he was politically useful, loyal to the Union, and wildly effective at self-promotion. Sickles respected Lincoln, perhaps because Lincoln didn’t judge him for the things others never forgot—like adultery, murder, or insubordination. It was a pragmatic, oddly warm relationship—the honorable statesman and the rogue with a cannonball scar and a murder rap.

One of the great debates of the Sickles’ movement is whether it was a smart move or a dumb move. There is no doubt that not following orders isn’t a sign of working well with others, but Sickles wasn’t the kind of man to let that bother him. Given the fact that III Corps was crushed in this maneuver, one could say, rightfully, that it was a dumb move from that perspective. This decision led to the destruction of his III Corps; it threatened the entire left flank of the Union defense. By uncovering both of his flanks, including Little Round Top, and not telling anyone what he was up to, he put Meade at a serious disadvantage. The prosaic truth, though, is that it might have saved the battle. Longstreet arrived with the intent of attacking north but found III Corps waiting; this forced the attack eastward. Longstreet’s attack was supposed to go north, up the Emmitsburg Turnpike, landing on Cemetery Ridge. Instead, the attack direction was east, across the turnpike, landing further south than Lee had intended. The original idea was for an attack on the Union center, not its left flank. When Longstreet and Hood saw the position Sickles had taken, they knew that Lee’s plan was no longer viable; they couldn’t attack northwards while the Peach Orchard was in Union lines.

The argument that it was a really smart move that saved the battle does not deny that Sickles had no idea what he was doing, that he was insubordinate, that he threatened the whole union line, and that many soldiers died that day because of his decision.

Congressional Investigation

After the war, Sickles spent years smearing General George Meade, the commander at Gettysburg. Sickles claimed he had saved the day, not Meade. After Gettysburg, while other generals returned to quiet retirement or relative obscurity, Daniel Sickles launched a political campaign to rewrite the history of the battle—and to bury General George Meade/ Sickles hated Meade because Meade didn’t praise him for his “bold” (unauthorized) move into the Peach Orchard and blamed him for nearly unraveling the Union line. So Sickles went to Congress and began whispering, testifying, and maneuvering.

He gave testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, a highly politicized Congressional body led by radical Republicans who distrusted West Point generals like Meade. Sickles portrayed Meade as timid, indecisive, and nearly incompetent, suggesting that the Union could’ve destroyed Lee’s army if only Meade had pursued him more aggressively. Sickles took advantage of Meade’s lack of popularity and quiet demeanor to shape the narrative to his own benefit.

Sickles claimed that his unauthorized advance drew the Confederates into a trap. His sacrifice (losing his corps and his leg) helped the Union win the battle. Meade was ready to retreat from Gettysburg, and Sickles and others persuaded him to stay. Much of this was self-serving or false, but it stuck.

And Meade—an actual West Point general who won the most important battle of the war—found that his reputation never fully recovered from Sickles’ campaign. Meade was reserved, disliked political games, and didn’t defend himself well in public. Sickles, by contrast, was a master of spin. He leaked to newspapers, charmed Congressmen, and turned Gettysburg into his victory. Even decades later, monuments popped up at the Peach Orchard and the line Sickles had created—many due to his efforts and fundraising.

Sickles used his role as a former congressman and war hero to full effect. He testified multiple times, always angling to elevate his role. He stayed close with key members of Congress, many of whom distrusted Meade and the Army’s high command. He helped shape early public memory of Gettysburg—not by rank or fact, but by force of personality. Sickles weaponized testimony to smear Meade and polish his legacy. He turned a near-disaster into a story of heroism and sacrifice. He influenced how the war and Gettysburg would be remembered. In short, Sickles lost a leg, nearly lost a battle, and then won the credit for the victory in Congress. Sickles received the Medal of Honor in 1897 (largely due to his own lobbying) for the winning the battle at Gettysburg.

Post-War Life

Lincoln’s assassination hit Sickles hard. Though politically and personally different, the two shared a strange kinship: both were outsiders, both survived enormous personal loss, and both were men who navigated immense scandal and contradiction. After the war, Sickles helped memorialize Lincoln, attending events and praising him as the savior of the Union—even as he continued pushing his own battlefield legend. Sickles knew a political stalking horse when he saw one, and he tied himself closely to Lincoln.

Daniel Sickles’ postwar life was as colorful, scandalous, and self-serving as his wartime career—maybe more so. Once the fighting stopped, he turned his full energy toward politics, diplomacy, monument-building, and intrigue, always placing himself at the center of the action (or at least the story).

U.S. Minister to Spain – A Scandal in Madrid

In 1869, President Grant appointed Sickles as Minister to Spain, a plum diplomatic post. And, true to form, Sickles created headlines: he reportedly had an affair with Queen Isabella II (already deposed but still influential).

He tried to negotiate the annexation of Cuba—a long-held American dream—but was far too erratic to be effective. He made diplomatic waves by openly supporting Cuban rebels against Spain, which caused confusion and tension. His time in Spain was glamorous, chaotic, and utterly Sickles. After a few years, Grant recalled him—he had outlived his usefulness and outworn his welcome.

Political Operator & Congressional Drama

Sickles returned to the U.S. and ran for Congress again in the 1880s. He won—because he still had political clout. His legend (and storytelling) still played well with veterans and the press. He positioned himself as the defender of Union veterans, advocating for pensions and memorials. He used his seat to promote Gettysburg preservation, always to highlight his own role. He remained a master of the behind-the-scenes political game, buttering up allies and undermining rivals.

Founding the Gettysburg National Military Park

Sickles played a central role in the creation of what would become the Gettysburg National Military Park. He was a founding member of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), created in 1864 to preserve the battlefield.

He used his political connections to secure funding, land purchases, and publicity, all while making sure his old positions were commemorated. He lobbied for national control of the battlefield, which Congress approved in 1895. The War Department took over the site, making it one of the earliest national military parks.

In the 1890s, Sickles was appointed chairman of the New York Monuments Commission, responsible for erecting state monuments at Gettysburg. Sickles had monuments built along the line he occupied on Day 2 of the battle—including the Peach Orchard, Wheatfield, and Devil’s Den area—even though that line had been a disaster militarily. He ensured his III Corps got prominent recognition. He blocked or delayed monuments to commanders and units that had criticized him. He boosted his image as a martyr who had saved the Union line—his missing leg became part of the mythos.

Sickles never got a monument of his own at Gettysburg—at least not an official one.. The monument on the field at Gettysburg to his brigade was supposed to include a bust of him. What happened to it? He allegedly stole the money given by charitable donations and kept it for himself. His later years were dogged by embezzlement accusations related to the New York Monuments Commission. In 1912, a bombshell dropped: $27,000 in funds had mysteriously disappeared. That’s nearly a million dollars in today’s money. Sickles was accused of misappropriating the funds, but he claimed he didn’t know where the money went. He never admitted guilt. He was removed from the commission, but never prosecuted—likely due to his fame, age, and connections. The scandal derailed efforts to give him an equestrian statue at Gettysburg. To this day, he’s the only corps commander at Gettysburg without a monument.

His reputation was so tainted by that point that even his allies backed away from a monument. But Sickles didn’t care—he had already built his legend into the park’s landscape. He argued that the entire battlefield was a monument to him. This isn’t surprising given the size of his ego. He may have lost a leg and almost a battle, but he won the memory war. He influenced how the battlefield was memorialized, ensuring his Peach Orchard line was heavily commemorated. Some say he preserved Gettysburg not for history’s sake, but to rewrite his role in it. He played a major role in the preservation of the Gettysburg battlefield, helping turn it into a national park.

American Scoundrel is truly the right description for this man, who demonstrated no evidence of a moral compass. He helped create the battlefield park. He influenced which sites were preserved and emphasized. He used monuments to reshape public understanding of his role. He made sure Gettysburg was about legacy, not just tactics, and very much his legacy.

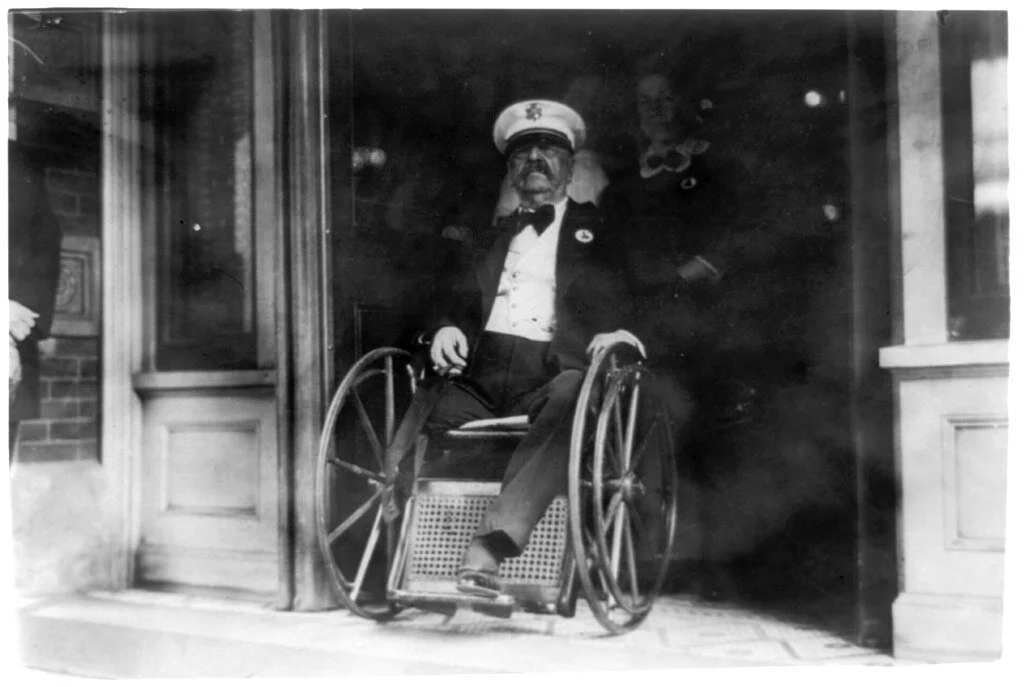

Daniel Sickles in 1911.

Legacy

Daniel Sickles remains a deeply divisive figure: Some see him as a self-promoting rogue and reckless commander. Others credit him with playing a pivotal role at Gettysburg. Historians often present both sides: bold, flawed, fascinating. If you like historical drama with real-life consequences, Sickles is your guy.

Historians, Civil War buffs, and battlefield guides have spent over a century arguing about how to rank, remember, and judge this uniquely outrageous figure. In the decades right after his death (1914, age 94), Sickles was remembered mostly as a scandalous but lovable rogue. Veterans who served under him remembered his charisma and bravery. He was still widely considered a hero of Gettysburg, thanks to his relentless mythmaking and the monuments his friends placed on the battlefield. He was seen as flawed—but entertaining, and above all, American in his contradictions.

But in the mid-20th Century, there was a backlash. As historical analysis became more rigorous, especially post-WWII, historians began to sharply reassess Sickles. He was criticized as a glory-hound, incompetent field commander, and blatant self-promoter. His decision to move his corps forward at Gettysburg was labeled insubordinate and disastrous, weakening the Union left and costing thousands of lives. He was accused of poisoning Meade’s legacy and distorting the historical record to elevate himself. By the 1950s and 60s, serious Civil War scholars often treated Sickles as a cautionary tale of political generals run amok.

Today, modern historians fall into two main camps: Villain or Disruptor. His decision at Gettysburg was irresponsible and disrespectful to the chain of command.

sleazy in politics and postwar behavior. No question, too, that he was self-serving—a saboteur of Meade’s legacy and battlefield truth, but his advance to the Peach Orchard disrupted Lee’s plan, despite disobeying orders. Historians like Garry Adelman and James Hessler have produced recent work that’s more nuanced, arguing that while Sickles was reckless, his maneuver may have inadvertently helped, and that his impact on battlefield preservation was immense.

Sickles was flamboyant, scandal-prone, and unrepentant. He can be remembered as: a heroic general, an ostentatious rogue; a man who lived a dozen lives (in one body, minus one leg). And perhaps most fittingly, a man who never stopped campaigning—even when the war was long over. He was:

· A murderer turned war hero

· A wounded general with a public skeleton (literally)

· A womanizer and political operator

· A man who could charm, offend, or politically outmaneuver almost anyone

He lived to age 94, never expressed regret, got away with all of it, and managed to ensure that we are still talking about him more than a century later. And there is no doubt that that is exactly the legacy that he wanted.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.