The Victoria Cross stands as one of the most revered and instantly recognizable military decorations in the world. Awarded "for most conspicuous bravery … in the presence of the enemy," it has come to symbolize the highest ideal of personal courage across the British and Commonwealth armed forces. Yet its creation was not inevitable. The medal was born out of a moment of national self-reflection, forged during a war that exposed the deficiencies of Britain's honors system and the heroism of ordinary soldiers in equal measure. Its conception, minting, and enduring legacy form one of the most compelling stories in military history.

Terry Bailey explains.

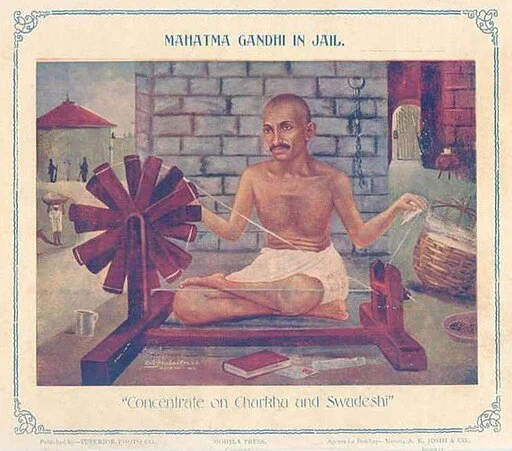

The front and back of Edward James Gibson Holland's Victoria Cross. Source: Royal Canadian Dragoons Archives and Collection, available here.

The Crimean War of 1853–1856 fundamentally reshaped Britain's approach to honoring gallantry. Prior to this conflict, no universal British award existed to recognize personal bravery on the battlefield. Instead, recognition tended to be tied to rank or social position, leaving countless acts of courage by common soldiers formally unacknowledged. The Crimean War changed this. Journalists, for the first time reporting directly from the front lines, brought stories of extraordinary heroism into Victorian homes. Reports of the Charge of the Light Brigade, the defense of the Alma, and the brutal conditions at Sevastopol stirred the public and embarrassed the government, highlighting the lack of a decoration that transcended class.

The idea for a new medal quickly took hold. Prince Albert, the Prince Consort, became one of the strongest advocates for the creation of a simple, egalitarian award. He envisioned a decoration that could be bestowed upon any serviceman—private or general—solely based on merit and bravery. Queen Victoria herself approved his vision, favoring a design that was dignified yet unpretentious. The result was a Royal Warrant issued on the 29th of January 1856, instituting a new honor: the Victoria Cross. It would be awarded sparingly and only for the most exceptional acts of valor performed in the presence of the enemy, making it a truly rare and exceptional distinction.

The first Victoria Crosses were minted in 1856, and the story of their material origin has become a key part of the medal's mystique. Tradition holds that they were made from the bronze of two Russian cannon captured during the Siege of Sevastopol. These heavy guns, relics of one of the fiercest battles of the war were transported to Woolwich, where they were broken down and melted to provide the raw material for the decoration. While later metallurgical examinations have raised questions about whether all the metal truly came from Russian guns, the symbolism of forging gallantry from captured weaponry has endured. The bronze was cast into small ingots, each used to create the distinctive cross pattée that has become synonymous with supreme bravery.

The raw material for the Victoria Cross remains a subject of fascination. A small supply of bronze, approximately 358 kilograms, has been safeguarded for more than a century and a half at the Ministry of Defence's base at Donnington. This stock is used exclusively for the casting of new medals, ensuring that each Victoria Cross shares a tangible connection to its Crimean War origins. Only a few ounces of bronze are needed for each medal, meaning the reserve is expected to last for many more generations of awards. The process of casting, finishing, and engraving each medal remains highly specialized and is carried out with deep respect for its historical lineage, preserving the continuity of tradition that began in the 1850s.

One particularly unusual feature of the first Victoria Crosses lies in their retrospective nature. Although the medal was formally instituted in 1856, the first awards recognized acts of bravery performed as far back as 1854. This meant that the earliest medals minted were created to honor deeds predating the very existence of the decoration. The inaugural investiture took place on the 26th of June 1857 in London's Hyde Park. Before a crowd of thousands, Queen Victoria herself presented sixty-two medals, many of which commemorated actions that had already become legendary in popular imagination. These first recipients set the tone for a decoration defined by humility, sacrifice, and the recognition of courage wherever it was found.

Throughout its history, the Victoria Cross has been awarded a total of 1,358 times since the medal's inception in 1856. This includes 1,355 individual recipients and three bars (second awards) for an additional act of valor. These three men, were Arthur Martin-Leake, Noel Chavasse, and Charles Upham, who all received the medal twice, earning a rare Bar for a second act of extraordinary valor. Their stories represent the pinnacle of human courage, each a testament to unwavering resolve in the face of overwhelming danger. From the trenches of the First World War, to the skies of the Second World War, to modern conflicts in the Falklands, Iraq, and Afghanistan, the medal has remained a constant, awarded sparingly to ensure its prestige and significance remain undiminished.

Today, the Victoria Cross occupies a unique place in the military culture of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth nations. Its design has remained almost unchanged since the first medal was cast. The obverse features a lion standing on the royal crown, above a scroll bearing the simple yet powerful inscription "For Valour." The crimson ribbon was selected by Queen Victoria herself, and its deep color has become iconic in its own right. The reverse of each medal is engraved with the name, rank, and unit of the recipient, as well as the date of the action for which it was awarded, personalizing each decoration as a permanent reminder of individual sacrifice.

The significance of the Victoria Cross extends far beyond its material form. It stands as a monument to the idea that bravery is not confined to rank, status, or background. Conceived at a time when society was rigidly hierarchical, the medal offered unprecedented recognition to ordinary soldiers whose courage would otherwise have gone unrecorded. Its survival into the twenty-first century speaks to the enduring relevance of its core principle: that exceptional valor deserves the highest honor a nation can bestow.

In tracing the history and conception of the Victoria Cross, from the battlefields of Crimea to the secure vaults of Donnington, a story is uncovered, not only of military decoration but of evolving national values. The medal remains a powerful symbol of courage, integrity, and humanity. It is a reminder that in the most desperate moments of conflict, individuals continue to demonstrate a level of bravery that transcends time, forging their place in history and inspiring generations to come.

The Victoria Cross endures because it represents far more than an award for bravery; it embodies a moral ideal that has remained remarkably constant despite profound changes in warfare, society, and the nature of conflict itself. From its origins in the aftermath of the Crimean War to its continued presence in modern campaigns, the medal has consistently affirmed that courage under fire is a universal human quality, worthy of the highest recognition regardless of rank, background, or circumstance. Its careful design, its symbolic material origins, and its deliberately restrictive criteria have ensured that the Victoria Cross has never been diminished by overuse or ceremony, but instead retains an almost sacred authority.

What ultimately distinguishes the Victoria Cross is its unbroken continuity. Each new award draws a direct line back to the first acts of valor recognized in the mid-nineteenth century, both materially through the bronze from which it is cast and philosophically through the values it represents. In an age where military technology and doctrine have evolved beyond anything its founders could have imagined, the essence of the medal remains unchanged: the recognition of selfless courage in the face of mortal danger. This continuity reinforces the Victoria Cross not as a relic of imperial history, but as a living tradition that continues to define the very highest standard of service and sacrifice.

In this sense, the Victoria Cross serves as a bridge between generations. It links the soldiers of Crimea with those of the world wars and the conflicts of the present day, uniting them in a shared narrative of extraordinary human resolve. Each recipient adds a new chapter to this story, yet none diminishes those that came before. Instead, the collective weight of these individual acts strengthens the medal's meaning, ensuring that it remains both a personal honor and a national symbol.

As long as courage is demanded in the service of others, the Victoria Cross will continue to hold its unique place in history. It stands as a quiet yet enduring testament to the capacity for bravery under the most extreme conditions, reminding society that while the circumstances of war may change, the values of courage, sacrifice, and integrity remain timeless.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Note:

The ribbon of the Victoria Cross varies by service branch, with dark crimson traditionally used for the British Army and Royal Marines, (today Royal Marine Commandos, while a deep blue ribbon was originally designated for awards to the Royal Navy. In practice, the crimson ribbon has become standard across all branches since the First World War, reflecting the unification of service distinctions while preserving the medal's historic origins.