Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain stands as one of the most compelling figures of the American Civil War, not because he was a professional soldier forged in a lifetime of military service, but because he was an intellectual and educator who rose to extraordinary leadership when history demanded it. Born on the 8th of September, 1828 in Brewer, Maine, Chamberlain grew up in a deeply religious and disciplined household. His father, a stern militia officer and shipbuilder, instilled in him a sense of duty and moral responsibility, while his mother encouraged learning and faith. Chamberlain excelled academically, displaying a gift for languages and scholarship that would define his early life. He attended Bowdoin College, where he studied theology and the classics, eventually becoming fluent in multiple ancient and modern languages. By the late 1850s, he was a professor of rhetoric at Bowdoin, seemingly destined for a quiet life of scholarship rather than war.

Terry Bailey explains.

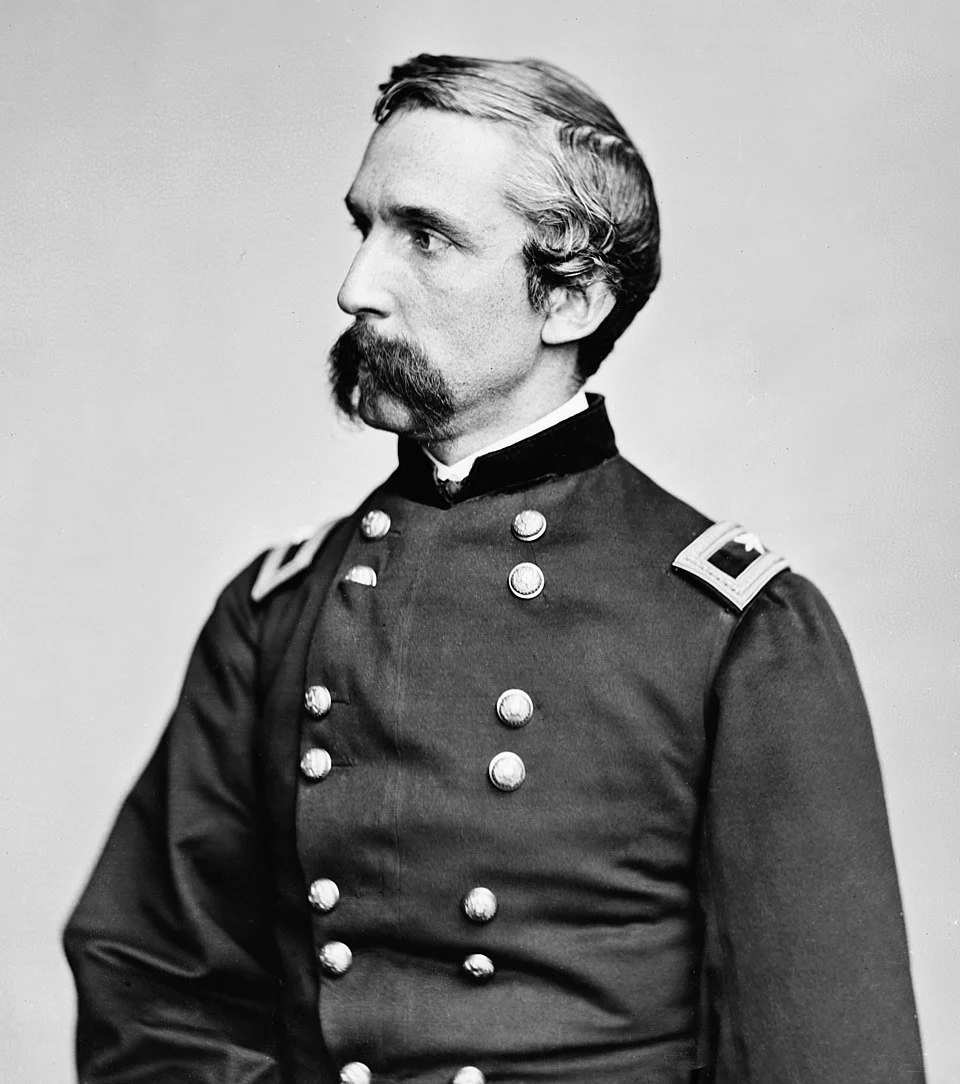

Joshua Chamberlain.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 profoundly unsettled Chamberlain. Though opposed to slavery and deeply committed to the Union, he initially remained at Bowdoin, torn between his academic responsibilities and what he saw as a moral obligation to serve. In 1862, he resolved the conflict decisively. Despite lacking formal military training, he requested a leave of absence to join the army, telling Bowdoin's president that the war represented a struggle for the soul of the nation. He was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry, a regiment composed largely of lumbermen and farmers, many of whom were older and physically tougher than their scholarly officer. Chamberlain won their respect not through bluster or harsh discipline, but through fairness, shared hardship, and a willingness to listen, qualities that would later prove critical under fire.

By the summer of 1863, Chamberlain had risen to command the 20th Maine, and his regiment found itself marching into history at Gettysburg. On the 2nd of July, 1863, the second day of the battle, the Union Army hastily extended its left flank to anchor on a rocky hill known as Little Round Top. The position was vital; if Confederate forces seized it, they could roll up the Union line and potentially decide the battle in their favor. The 20th Maine was placed at the extreme left of the Union position, with orders that could not have been clearer or more ominous: "Hold this ground at all hazards." There would be no reinforcements. If the regiment broke, the Union flank would collapse.

Throughout the afternoon, Chamberlain's men endured repeated assaults by the 15th Alabama and other Confederate units under Colonel William C. Oates. The fighting was close, chaotic, and brutal, conducted over boulders and through dense woods in sweltering heat. Each Confederate attack pushed closer to breaking the Union line, and Chamberlain was forced to stretch his regiment dangerously thin, bending his line back like a door hinge to prevent being flanked. Ammunition ran dangerously low. Men collapsed from exhaustion and heat. Chamberlain himself was everywhere along the line, steadying his soldiers, issuing calm orders, and absorbing the terror of combat without losing command of the situation.

As the final Confederate assault loomed, Chamberlain faced a grim reality. His regiment was nearly out of ammunition, and another attack would almost certainly overwhelm them. In that moment, he made one of the most audacious tactical decisions of the war. Rather than waiting passively to be overrun, Chamberlain ordered a bayonet charge. With a sweeping wheel to the left, the 20th Maine surged downhill, shouting and driving their bayonets into stunned Confederate troops who expected no such move from an exhausted and depleted enemy. The sudden offensive shattered the momentum of the Confederate attack. Many Southern soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured, and the rest fled. Little Round Top was held, the Union flank was saved, and the outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg and arguably the war itself tilted decisively in favor of the Union.

Chamberlain's actions at Gettysburg would later earn him the Congressional Medal of Honor, awarded in 1893. The citation recognized his "daring heroism and great tenacity" in holding Little Round Top against overwhelming odds. Yet the significance of his conduct lay not only in bravery, but in leadership and judgment under extreme pressure. Chamberlain demonstrated an intuitive understanding of morale, terrain, and timing, proving that decisive leadership could compensate for material disadvantage. His conduct became a textbook example of initiative at the tactical level, studied by soldiers long after the war. Chamberlain's wartime service did not end at Gettysburg, and the war would exact a terrible physical toll on him. He was promoted to brigadier general and continued to serve with distinction in the Overland Campaign of 1864. At the Battle of Petersburg, he was shot through the hip and groin, a wound so severe that he was expected to die. Grant promoted him on the battlefield as a final honor, but Chamberlain survived after months of agony and recovery. He returned to duty despite chronic pain and lasting disability, embodying the same determination that had defined his stand on Little Round Top.

In one of the war's most symbolic moments, Chamberlain played a prominent role at its conclusion. On the 12th of April, 1865, he was selected to command the Union troops receiving the formal surrender of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. In a gesture of reconciliation rather than triumph, Chamberlain ordered his men to salute the defeated Confederates as they laid down their arms. The act reflected his belief that the war had been fought to preserve the Union, not to humiliate the South, and it earned respect from former enemies, including Confederate General John B. Gordon.

After the war, Chamberlain returned to civilian life but never escaped the shadow of his service. He became president of Bowdoin College, guiding the institution through a period of reform and expansion, and later served four terms as governor of Maine. His postwar years were marked by public service, writing, and continued reflection on the meaning of the war. He authored several books and essays, offering thoughtful and often philosophical interpretations of the conflict and its moral dimensions. Though plagued by pain from his wartime wounds for the rest of his life, he remained active and engaged well into old age. Joshua Chamberlain died in 1914, one of the last prominent Civil War generals, and was the final veteran to die from wounds received in that conflict. His legacy endures not merely because of a single dramatic charge, but because his life embodied the idea of citizen-soldiership at its finest. A scholar who became a warrior, a leader who combined compassion with resolve, Chamberlain's stand at Little Round Top remains a powerful reminder of how individual courage and judgment can shape the course of history at its most critical moments.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain's life and legacy ultimately transcend the dramatic moments for which he is most famous. His story is not merely one of battlefield heroism, but of moral conviction carried into action, of intellect fused with courage, and of leadership rooted in principle rather than ambition. At Little Round Top, Chamberlain did more than save a tactical position; he exemplified the capacity of an ordinary citizen to rise to extraordinary responsibility when the fate of a nation hung in the balance. His decisions were shaped not by rigid military doctrine, but by empathy for his men, clarity of purpose, and a profound sense of duty to something larger than himself.

What distinguishes Chamberlain from many of his contemporaries is the continuity between his wartime conduct and his postwar life. The values that guided him in combat—discipline tempered by humanity, firmness balanced with reconciliation—were the same values he carried into education, politics, and public service. His salute to the defeated Confederates at Appomattox symbolized his belief that the war's true victory lay not in vengeance, but in the restoration of a fractured nation. This act, quiet yet powerful, reflected a deeper understanding of what lasting peace required and underscored his lifelong commitment to unity and moral responsibility.

Chamberlain's enduring significance lies in the way his life challenges simple definitions of heroism. He was not born a soldier, nor did he seek glory, yet he became one of the war's most respected leaders through resolve, adaptability, and an unwavering ethical compass. His physical suffering after the war, borne without bitterness, further reinforces the depth of his character. Even as his wounds shaped his final decades, he continued to serve, teach, write, and reflect, determined that the sacrifices of the Civil War should be understood and remembered with honesty and purpose.

In the final measure, Joshua Chamberlain represents the highest ideals of citizen leadership. His stand at Little Round Top remains a defining moment in American history, but it gains its full meaning only when viewed within the broader arc of his life, a life devoted to learning, service, reconciliation, and moral courage. Through his actions in war and peace alike, Chamberlain left a legacy that speaks not only to the past, but to the enduring power of individual conscience and leadership in shaping the course of history.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Notes:

The wounds Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain received during the Civil War had a profound and lasting impact on his health, shaping the remainder of his life and ultimately contributing to his death. On the 18th of June 1864, during the Battle of Petersburg, Chamberlain was struck by a Minie ball that passed through his right hip and groin, exiting near the bladder and urethra. The injury was considered mortal at the time; blood loss was severe, infection was likely, and the medical practices of the era offered little hope of recovery. He survived only through extraordinary resilience and prolonged medical care, but the damage inflicted by the wound could never be fully healed.

In the years that followed, Chamberlain endured chronic pain, recurring infections, and serious urological complications as a direct result of the injury. The wound left him with long-term damage to his urinary system, including fistulas and strictures that caused frequent obstruction, inflammation, and bleeding. These conditions required repeated medical interventions throughout his life and often left him weak, feverish, and exhausted. Periods of relative health were frequently interrupted by painful relapses, making daily activity unpredictable and physically taxing. Despite this, Chamberlain persisted in public life, masking the severity of his condition behind an outward appearance of energy and resolve.

As he aged, the cumulative effects of the wound worsened. Recurrent infections increasingly taxed his immune system, while chronic inflammation and impaired urinary function led to progressive organ stress. By the early twentieth century, his body was less able to recover from the complications that had plagued him since the war. In 1914, nearly fifty years after being wounded, Chamberlain succumbed to complications directly linked to his Petersburg injury, making him the last Civil War veteran to die from wounds sustained in that conflict. His death served as a stark reminder that the suffering of war often extends far beyond the battlefield, lingering silently for decades after the guns have fallen silent.

Chamberlain's long struggle with his wounds adds a deeper dimension to his legacy. His postwar achievements in education, governance, and public life were accomplished not in spite of discomfort, but in the midst of persistent physical suffering. That he continued to serve with dignity and determination, even as his health steadily declined, underscores the extraordinary endurance that defined him as both a soldier and a citizen. His life stands as a testament to the hidden, lifelong costs of war and the resilience required to bear them.