Smedley Darlington Butler stands as one of the most formidable and paradoxical figures in United States military history, a Marine whose career traced the arc of American power abroad from the age of imperial interventions to the disillusionment that followed the First World War. Born on the 30th of July, 1881 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, into a prominent Quaker family, Butler's path to martial life seemed at odds with his upbringing. His father was a U.S. congressman, and the family tradition emphasized public service, but not violence. Yet at the age of sixteen, stirred by the outbreak of the Spanish–American War and driven by a precocious sense of duty and adventure, Butler lied about his age to secure a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps. That impulsive decision began a career that would see him repeatedly at the sharp edge of American foreign policy.

Terry Bailey explains.

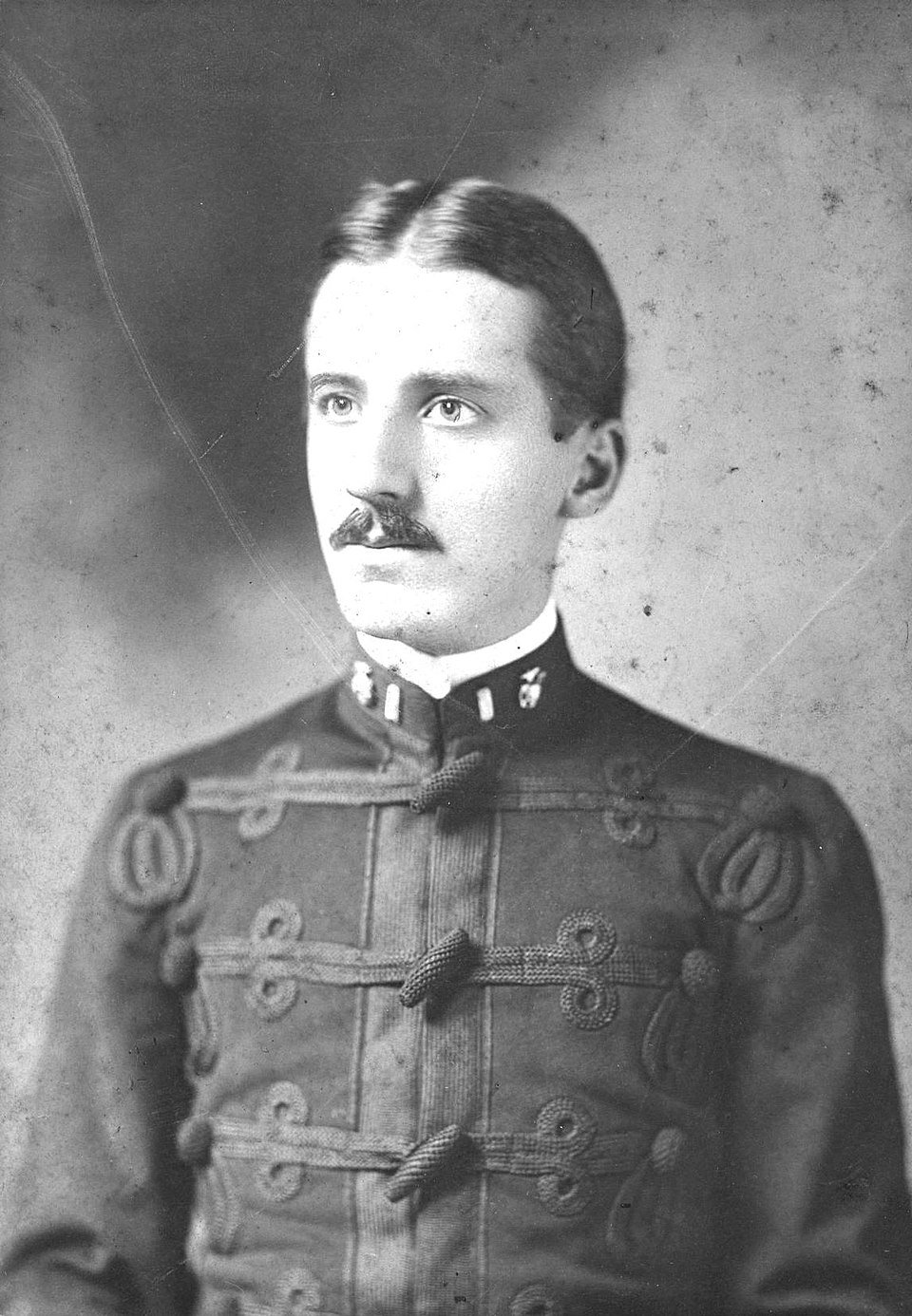

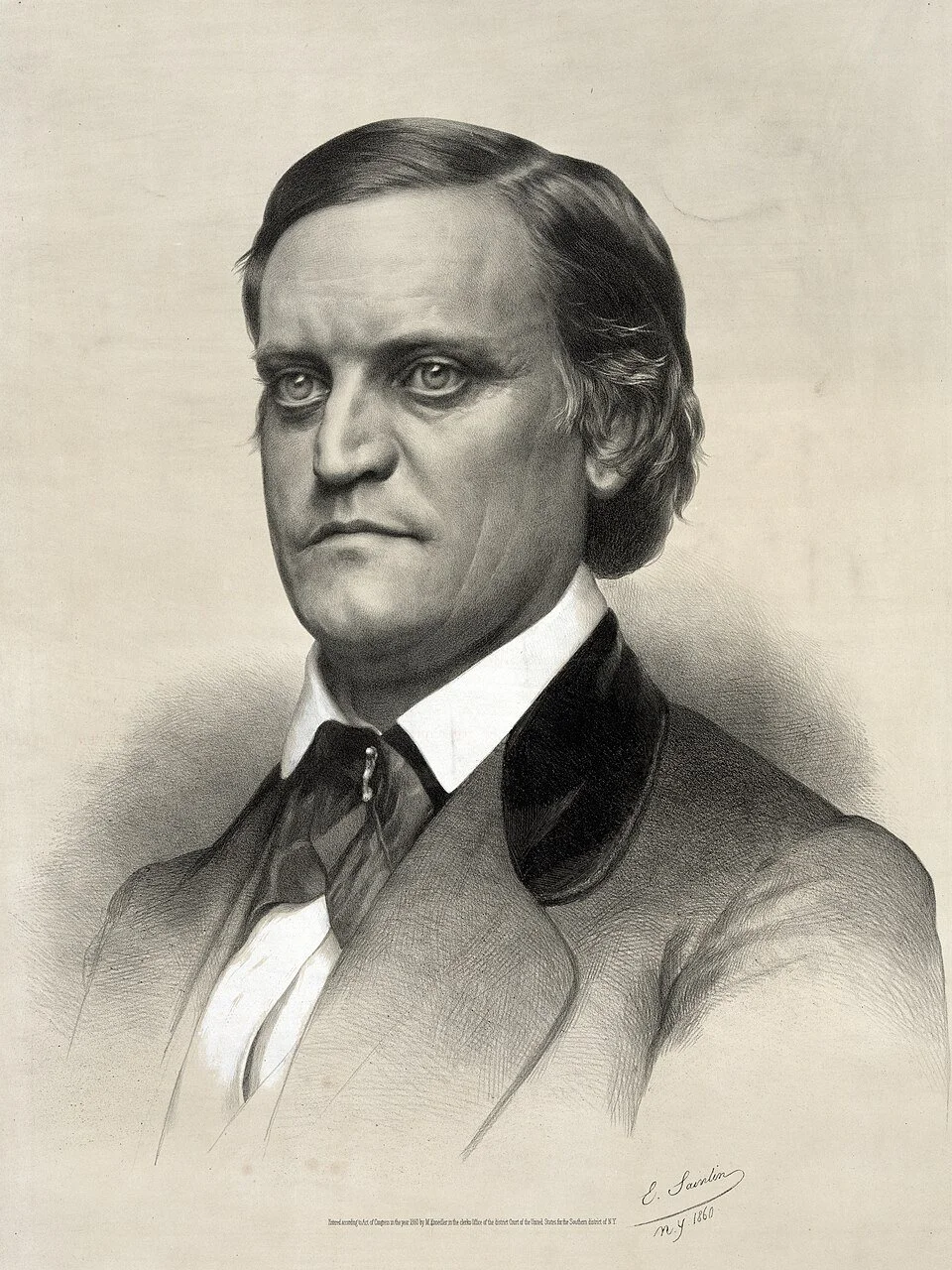

Smedley Butler early in his earlier years - said to be 1898. From the Smedley Butler Collection (COLL/3124), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections, available here.

Butler's early service immersed him in the era's so-called "small wars," interventions designed to protect American interests overseas. He fought in China during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, where multinational forces moved to relieve foreign legations besieged in Beijing. There, Butler was wounded in combat and displayed the aggressive leadership that would become his hallmark. He later returned to China during subsequent interventions, gaining firsthand experience of expeditionary warfare in unstable political environments. These deployments, along with service in the Caribbean and Central America, shaped Butler into a hardened officer who believed that personal example—leading from the front under fire—was the essence of command.

The first of Butler's two Medals of Honor was earned during the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, in April 1914. The intervention arose from the chaotic conditions of the Mexican Revolution and a diplomatic crisis triggered by the Tampico Affair, in which U.S. sailors were briefly detained by Mexican federal forces. Determined to prevent a shipment of arms from reaching the regime of Victoriano Huerta, President Woodrow Wilson ordered the seizure of Veracruz. Butler, then a major, found himself in intense urban combat as Marines and sailors advanced street by street against determined resistance. Over two days of fighting, Butler repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire while directing his men, maintaining momentum amid confusion and danger. His conspicuous bravery, calm leadership, and disregard for his own safety were credited with helping to secure key objectives during the assault. For this conduct, he received the Medal of Honor, recognizing his extraordinary heroism in a complex and politically sensitive operation.

Butler's second Medal of Honor came the following year during the U.S. intervention in Haiti, another campaign rooted in American concerns over political instability and foreign influence in the Caribbean. In November 1915, Butler led an attack on Fort Rivière, a stronghold held by Caco insurgents resisting the occupation. The fort, an old French structure perched atop a steep hill, was considered nearly impregnable. Rather than ordering a prolonged bombardment, Butler personally led a small assault force up the hill under fire. Discovering a narrow entrance, he and his men forced their way inside and engaged the defenders at close quarters. The sudden, aggressive attack collapsed the resistance within minutes. Butler's decision to lead the assault himself, coupled with his audacity and tactical judgement, was deemed decisive. Awarded a second Medal of Honor, he joined a very small group of Americans to have received the nation's highest military decoration twice.

During the years that followed, Butler's career continued to reflect the expanding global reach of the United States. He served on the Mexican border during the 1916 crisis sparked by Pancho Villa's raids, helping to secure frontier regions amid fears of wider conflict. When the United States entered the First World War, Butler was promoted to brigadier general and assigned logistical and training responsibilities rather than frontline combat. Most notably, he commanded the Marine base at Brest in France, where he worked to impose order and efficiency on a massive, chaotic port operation essential to sustaining the American Expeditionary Forces. Though frustrated by bureaucracy and the lack of combat command, his energy and organizational drive earned him respect and further advancement.

After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1931 as a major general, Butler underwent a profound transformation. Drawing on his decades of experience in foreign interventions, he became an outspoken critic of American militarism and corporate influence over foreign policy. His 1935 pamphlet War Is a Racket argued that many of the campaigns he had fought in served economic interests rather than national defense, a striking repudiation from one of the most decorated Marines in history. Butler spent his final years lecturing and writing, admired by some for his candor and criticized by others for his blunt attacks on the establishment. He died in 1940, leaving behind a legacy defined by extraordinary personal courage, relentless leadership in battle, and a rare willingness to question the very system he had served so ferociously.

Smedley Butler's life captures the contradictions of his age: a fearless warrior of America's overseas expansion who later became one of its sharpest internal critics. His two Medals of Honor testify to moments of undeniable heroism under fire, while his later words invite reflection on the costs and purposes of the wars that shaped him. Few American military figures embody both the triumph and the unease of U.S. power abroad as fully as Smedley Darlington Butler.

Smedley Darlington Butler's story ultimately resists any simple verdict, and it is precisely this complexity that secures his enduring significance. As a young Marine officer, he personified the aggressive confidence of a rising power, repeatedly placing himself in harm's way and earning the devotion of the men he led through sheer physical courage and uncompromising example. His two Medals of Honor were not products of chance or symbolism, but of a consistent pattern of behavior: decisive action, personal risk, and an unshakeable belief that a commander's duty was to share the dangers of those he commanded. In this sense, Butler stands comfortably among the most formidable combat leaders in American military history.

Yet it is the second act of his life that elevates him beyond the narrow confines of martial achievement. Butler's post-retirement denunciation of the very interventions that had defined his career did not erase his service; rather, it reframed it. Few figures have possessed both the authority and the moral courage to interrogate their own legacy so publicly. When Butler condemned war as a racket, he did so not as an outsider or a theorist, but as a man who had fought, bled, and commanded in the field. His critique drew its power from lived experience, forcing contemporaries—and later generations—to confront uncomfortable questions about the relationship between military force, national interest, and economic power.

In the end, Butler's legacy lies not only in the battles he fought or the decorations he earned, but in the intellectual honesty with which he confronted the meaning of those experiences. He remains a symbol of both the heights of personal bravery and the capacity for reflection and dissent within the military tradition itself. In embodying the courage to fight and the courage to question, Smedley Darlington Butler occupies a rare and uneasy place in American history—one that continues to challenge how heroism, patriotism, and power are understood.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Notes:

Tampico Affair

The Tampico Affair was a brief but consequential diplomatic incident between the United States and Mexico in April 1914, occurring during the height of the Mexican Revolution. At the time, Mexico was deeply unstable following the overthrow and assassination of President Francisco Madero in 1913, an event that brought General Victoriano Huerta to power. The United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, refused to recognize Huerta's government, viewing it as illegitimate and born of treachery. This tense political backdrop meant that even minor incidents carried the potential for serious international repercussions.

The affair itself began on the 9th of April, 1914, when a small group of U.S. Navy sailors from the gunboat USS Dolphin went ashore at the Mexican port of Tampico to purchase fuel. They were arrested by Mexican federal troops, who suspected them of entering a restricted military area. Although the sailors were quickly released once their identity was established, the local Mexican commander failed to offer a formal apology. Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo, commanding U.S. naval forces in the area, demanded not only an apology but also a 21-gun salute to the American flag as a public gesture of respect.

Huerta's government agreed to issue an apology but refused to authorize the salute, arguing that it would compromise Mexican sovereignty and imply submission to the United States. President Wilson seized upon the refusal as evidence of Huerta's hostility and disrespect, and he used the incident to seek congressional approval to employ armed force. The Tampico Affair thus became less about the arrest itself and more a symbolic confrontation over national honor, legitimacy, and diplomatic recognition.

The immediate consequence of the affair was the U.S. occupation of the port of Veracruz later in April 1914, aimed at preventing a German arms shipment from reaching Huerta's forces. While the occupation was not a direct response to the Tampico incident alone, the affair provided the political justification Wilson needed to escalate U.S. involvement. In the broader context of U.S.–Mexican relations, the Tampico Affair exemplified how revolutionary instability, wounded national pride, and great-power diplomacy could rapidly turn a minor local misunderstanding into an international crisis.