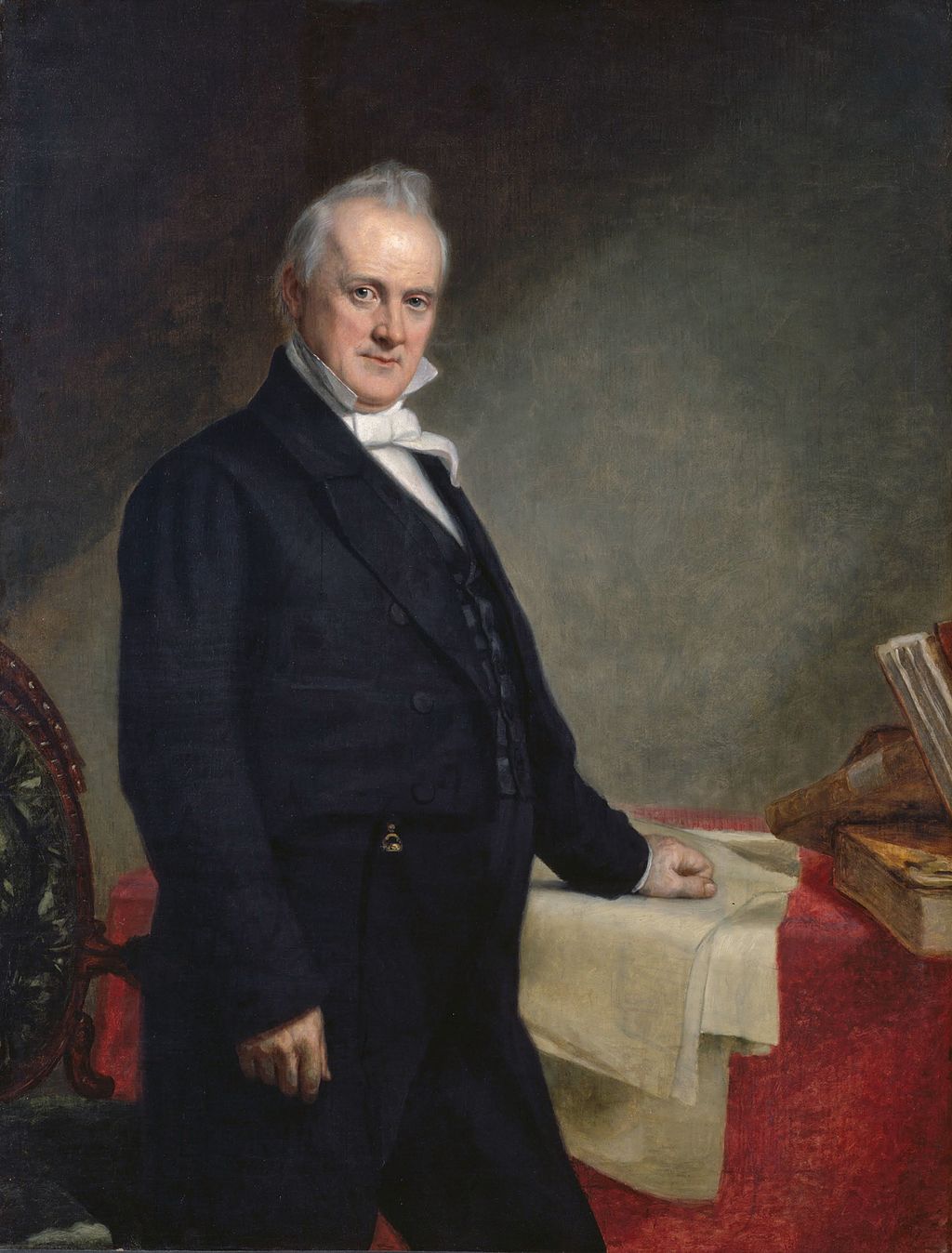

“Good Queen Bess,” “Gloriana,” or most controversial of all, “The Virgin Queen,” was the last of the five monarchs of the House of Tudor but also one of the most famous and influential. Her 44-year reign oversaw a glorious transformation of a politically and religiously unstable nation into one of the Great Powers in Europe and was subsequently referred to as England’s Golden Age.

Yet, behind her achievements and beneath her façade, Elizabeth Tudor is a woman we still know little of in personal regards. One of the greatest questions pertaining to her personal life is why this great queen never married. Historians have debated and speculated the reasons why this is with conflicting answers.

The closest reasons lay most clearly in her early life from her ill-fated mother, her quick-tempered father, and a predatory stepfather. Reasons both personal and political may have disenchanted Elizabeth from a tender age to defy centuries of English history’s expectation of a married monarch, even more so of a female monarch.

The unwelcome birth

The birth of a girl, Elizabeth, in September 1533 was a disappointment to her father, King Henry VIII of England, possibly the “worst” disappointment of his life according to Tudor historian Heather Sharnette of Elizbabethi.org. Henry had done the unthinkable in contemporary times by breaking from the Church of Rome and defying the Pope that had refused to annul his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry his mistress, the dazzling Anne Boleyn. In his defiance, he had destroyed monasteries and abbeys and put to death loyal friends for defending their faith, only to be given what he already had, a daughter. There was little celebration for her birth and the magnificent Christening that had been planned for the longed for baby prince went ahead anyway.

As long as Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, was Queen of England, Elizabeth was treated as the most important person in England, only second to her father and was even proclaimed “princess,” the title to the heiress to the throne. However, this was only short-lived as Queen Anne could not produce any more surviving children. Henry’s passionate love for her had died down. Her sharp tongue, fiery intelligence, and stubbornness that had initially appealed to him began to irritate him. After Catherine of Aragon’s death in January 1536 and the subsequent miscarriage of a boy, Henry was free to dispose of Anne without facing petitions to return to Catherine. Only four months later, Anne was arrested and faced trumped up charges of witchcraft, adultery, and incest. Not surprisingly, she was found guilty and sent to the Tower of London where she was to await her penalty: death.

The decision to die via burning or decapitation was up to Henry who chose the latter and showed a single streak of mercy towards the woman he once loved by granting her request to be executed by sword instead of the customary axe. Anne was beheaded on May 19, 1536 on Tower Green. Elizabeth was only two and a half years old.

After her mother’s death

The death and disgrace of her mother left little Elizabeth’s lifestyle greatly changed. She was probably far too young to be emotionally affected by her mother’s execution. The marriage between her father and mother was annulled and Elizabeth was declared a bastard with her title of Princess stripped from her. From a young age, Elizabeth took after her mother’s shrewd intelligence and remarked on the change upon her: “How haps it governor, yesterday my Lady Princess, today but my Lady Elizabeth?”

Just eleven days after her mother’s execution, Henry married her lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. With Elizabeth’s new status, her governess found that the little girl’s needs were being ignored even writing to the king to ask him to send for more clothes as Elizabeth had grown out of everything.

In October of 1537, after twenty-eight years and two wives, Henry finally sired the longed for son, Prince Edward VI. Only a few days later, Jane Seymour died and the king was crushed at her loss. Now Edward, like Elizabeth, would grow up motherless and the two would share a close bond grounded on age proximity, religion, and their mutual passion for learning. Though Elizabeth was on friendly terms with her half-sister, Mary, the sisters were never close. This relationship would dangerously sour for Elizabeth in later years.

Following the death of Jane Seymour and Henry’s emergence from seclusion, marriage negotiations began once again on behalf of the king’s fiercely Protestant advisors, Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer, who maneuvered Henry to marry the mildly Protestant Duke of Cleves’ sister, Anne. They were married in January 1540 after an awkward, disastrous first meeting. Elizabeth now had a second stepmother and according to Italian historian, Gregorio Leti, who wrote the following account two centuries after the event occurred of Elizabeth writing to her father for permission to meet her new stepmother, Anne of Cleves. Anne, upon giving the letter to her husband, Henry “took the letter and gave it to Cromwell” ordering him to write a reply: “Tell her,” he remarked. “that she had a mother so different from this woman that she ought not to wish to see her.” There is controversy as to whether this is true but Elizabeth was eventually brought to Court from Herford Castle to meet Anne.

Anne, in turn, was reportedly “charmed by her beauty, wit and… that she conceived the most tender affection for her,” and to have Elizabeth “for her daughter would have been greater happiness to her than being queen.” Henry, on the other hand, was not sharing the sentimental atmosphere; as soon as he endured a wedding he could not evade, he become resolute on obtaining a divorce. Six months later, he finally achieved this upon the discovery of a previous marriage contract (but no marriage) to the Duke of Lorraine and on the grounds of non-consummation (the reason being her cruelly remarked appearance).

King Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne of Cleves was his shortest and least influential marriage but no doubt it may have had the most profound impact on young Elizabeth by this time. She was probably too young to be deeply affected by the deaths of her mother and first stepmother, but by the time Anne of Cleves appeared into her life, she was almost seven years old and better able to comprehend the functions of Court life and her father’s effect on them. Anne was the first stepmother Elizabeth had formed a notable bond with and upon the king’s second divorce, Anne had requested of the king permission to still see Elizabeth which the king agreed to. This bond would remain strong between the two ladies until Anne’s death in 1557. Anne of Cleves was considered the luckiest of Henry VIII’s wives. Anne’s influence of her stepdaughter’s unmarried state was once supposedly referenced by Queen Elizabeth herself to Count Feria, the Spanish Ambassador, who said that she had “taken a vow to marry no man whom she has not seen, and will not trust portrait painters.”

Catherine Howard becomes Queen

Almost immediately upon her father’s second divorce, he wed the dazzling and witty Catherine Howard. Historians debate on how old she was when she wed the 49-year old Henry. Most calculate that she was about 15 years old and according to Charles de Marillac was “rather graceful than beautiful, of short stature, etc.” Personality-wise, Catherine was described as charming, sensual, and obedient which proved a welcoming contrast to her first cousin, Anne Boleyn. Many observers noted that he showed the most generosity and affection to her than his other wives. De Marillac noted, the “King is so amorous of her that he cannot treat her well enough and caresses her more than he did the others.”

Once Henry acknowledged her as queen, “she directed that the princess Elizabeth should be placed opposite to her at table, because she was of her own blood and lineage.” At marriage festivities, Catherine “gave the lady Elizabeth the place of honour nearest to her own person.” Elizabeth’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Boleyn was a sister to Edmund Howard, Catherine’s father. The young new queen reached out to Elizabeth to formulate a bond with her kinswoman by arranging for her to be taken from Suffolk Place to Chelsea where Catherine joined her. As of November 1541, Catherine presented the eight-year old Elizabeth with a jewel as a kind gesture.

The fall of Henry VIII’s fifth wife came after John Lascelles revealed to Archbishop Cranmer the Queen’s promiscuity during her years at the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk’s estate, her step-grandmother. Many young women residing there “entertained” men after hours and Catherine was among them. When she was 13, Catherine engaged in physical relations with Francis Dereham after being earlier involved with her music teacher, Henry Manox.

Cranmer and Lascelles were both ardent Protestants while Catherine came from a conservative Catholic and undoubtedly powerful and influential English noble family. Cranmer launched a full-scale investigation that resulted in allegations of Catherine’s intimacy with Thomas Culpeper, a member of the king’s privy chamber, after her marriage to Henry.

Under interrogation (possibly torture), Culpeper admitted being in love with Catherine and “persisted in denying his guilt and said it was the Queen who, through Lady Rocheford, solicited him to meet her in private in Lincolnshire, when she herself told him that she was dying for his love.” Culpeper rebuffed claims that they had committed adultery despite their secluded time together.

Regardless, the Council felt there was enough evidence because Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, Catherine’s lady-in-waiting, confessed to helping them arrange their meetings and implied there was a physical relationship between them. The most damning evidence against the queen was a letter from Catherine found in Culpeper’s belongings.

When the King was informed of the accusations by a document left for him in his church pew, his quick temper exploded. Supposedly, he demanded a sword to slay her himself as she would never have “such delight in her inconstancy as she would have torture in her death.” Catherine was arrested and taken to the Tower of London. On the night before her execution, Catherine asked for a block to be brought to her so that she could practice placing her head on it.

On February 13, 1542, the fifth teenage Queen of Henry VIII was executed, “in the same spot where Anne Boleyn had been executed. Her body was then covered [with a black cloak] and her ladies took it away,” recounted Ambassador Chapuys to Charles V. No records survive of Elizabeth’s reactions to the execution of her stepmother and cousin or the loss of any of her stepmothers for that matter. We can, though, infer her reaction through the text of Larissa J. Taylor-Smither’s article, “Elizabeth I: A Psychological Profile” that states that the “shock of Catherine Howard’s execution (at the impressionable age of eight) would have been more immediate, for even if Elizabeth had not been especially close to her young stepmother, Catherine’s sudden extinction must at the very least have had a powerful effect on her subconscious.”

Henry VIII’s sixth wife

Following the execution, Henry VIII passed a law requiring all future queens of England to disclose any ‘indiscretions’ and possess chaste pasts. That certainly narrowed the list for Henry’s next selected wife. A notable candidate by the name of Katherine Parr seemed ideal; she was charming and cordial, pleasant to both nobles and servants and possessed sensibility and was a skilled conversationalist. She was also experienced with stepchildren through her two previous husbands.

It is certainly remarkable that she was the only one of Henry’s brides that did not want to marry him. Historians surmise that reasons range from her competence to see the pattern of dangers in marrying him to falling in love with Thomas Seymour, Lord High Admiral. Despite her reluctance to enter a marriage she couldn’t back out of, this was her chance, she believed, to promote the Protestant Reformation in England and the promotion of her family. As Queen, Katherine used her influence with the King to bring his children to Court to see their father more. Katherine was already well acquainted with Henry’s eldest child, Mary, as Katherine’s mother was a lady-in-waiting to Mary’s mother. Katherine “greatly admired her [Elizabeth’s] wit and manners.” A letter survives of the 10-year old Elizabeth writing with gratitude and praise at Katherine’s gesture to bring them to court. An excerpt from the letter reveals Elizabeth’s warmness towards her new and fourth stepmother: “…So great a mark of your tenderness for me obliges me to examine myself a little, to see if I can find anything in me that can merit it, but I can find nothing but a great zeal and devotion to the service of your Majesty.”

Between the summers of 1543 and 1544, historians speculate that Elizabeth offended her father in some way that led to her banishment to Ashridge near the Hertfordshire-Buckinghamshire border. Katherine still kept in contact with her stepdaughter and Elizabeth conveyed her belief that the young girl was “not only bound to serve but also to revere you with daughterly love…” Henry was abroad fighting against France and left Katherine as Regent in his absence. This was the first time Elizabeth witnessed firsthand a woman’s ability to rule on her own and revealed Henry’s confidence in his wife. Katherine successfully convinced the King to let Elizabeth join her at Hampton Court again, signifying their mother-daughter bond.

However, Katherine’s place and life was almost stripped from her upon two men attempting to arrest the Queen on the King’s orders. They were Thomas Wriothesley, 1stEarl of Southampton, Lord Chancellor and Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, who convinced Henry that she concealed radical religious leanings and increased his irritation with her recently expressed views. Wriothesley arranged for forty yeomen of the guard to accompany him with the arrest warrant and crept upon the Queen while she was in Henry’s company at Whitehall gardens.

Unbeknownst to Wriothesley, Katherine had been warned and hurried to her husband to explain herself and apologize. She assured him that she had not discussed theological meanings to lecture him but to learn from him and to distract him from the pain in his leg. Henry forgave her and upon Wriothesley’s arrival to arrest her, the King severely reprimanded him and sent him off. Barely escaping Henry’s wrath that claimed his previous wife, Katherine never again spoke out against the religious establishment. Katherine’s deep love of learning was shared with Elizabeth and she took charge of her education, employing Protestant and humanist tutors.

After Henry VIII

Following the King’s death in 1547, Katherine married the love of her life, Thomas Seymour. Thomas Seymour was shrewdly ambitious and the new king’s uncle and set his sights on Elizabeth as a possible wife and closer step to the throne. Finally catching onto her husband’s inappropriate advances on the 14-year old Elizabeth, Katherine removed her from her household at Chelsea in 1548 to the household of Anthony Denny and his wife at Cheshunt. Katherine was to go into confinement as the time for giving birth drew near, which would have allowed Seymour unlimited access to the vulnerable girl. It is likely Katherine removed Elizabeth for her own safety rather than to punish her. Katherine gave birth to a baby girl, Mary, in August 1548 and died eight days later of puerperal fever.

With Katherine now dead, Thomas Seymour’s attempts at wooing Elizabeth became more aggressive. Thomas, envious of his brother’s title as Lord Protector of the 9-year old Edward VI, also grew more serious in his quest for power. In 1549, Thomas was caught attempting to break into the King’s apartments at Hampton Court Palace and was arrested and sent to the Tower of London. His associates were arrested, including Elizabeth and her governess, Kat Ashley. She was interrogated for weeks and the flirtatious incidents between Elizabeth and Thomas Seymour were revealed but there was no evidence of Elizabeth conspiring with Thomas against the King. Thomas was convicted of treason and beheaded on March 20, 1549. Elizabeth narrowly escaped conviction.

From the time of her mother’s execution to the death of her most influential stepmother from childbirth, Elizabeth had witnessed the disposal and unstable position of her father’s many queens. The seventeen-year old Henry had begun his reign in 1509 as a popular, pleasant and seemingly sensible monarch. His later years however were marked by violence and tyranny with a formidable quick temper, with theories behind this sudden change in personality ranging from a jousting accident in 1536 to mental deterioration at his wives’ repeatedly failed pregnancies. Henry’s constant mood swings no doubt had an effect on the position of the young Elizabeth and like her half-sister Mary; her illegitimate status had prevented a marriage negotiation as long as her father lived.

From Edward to Mary

In 1553, King Edward VI was fifteen years old and, despite a relatively healthy childhood, had contracted a form of consumption, possibly tuberculosis. When it became clear that the boy would not survive, the new Lord Protector, John Dudley, schemed with the dying king to name a Protestant successor instead of his half-sister, Mary who was an ardent Catholic and would have reversed Edward’s Protestant reforms. An heir(ess) was named – his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, an equally committed Protestant. To John Dudley’s advantage, Jane was also his daughter-in-law. Edward died on July 6 1553, just six years into his reign. Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen three days later. However, just nine days into Jane’s “reign,” she was deposed by Mary and her army of supporters. Mary was proclaimed Queen of England on July 19, 1553 in London. John Dudley was arrested and later executed along with Jane Grey and her husband. At first, Mary I viewed Jane as a mere pawn of her husband’s and father-in-law’s treasonous ambition, but after the Protestant Wyatt’s Rebellion, Mary was left with no choice but to put her cousin to death lest she become a figurehead of the Protestant movement that Mary had means to crush.

Upon Mary I’s start as Queen of England, relations between the two half-sisters remained cordial despite their religious differences. It would only sour after Wyatt’s Rebellion which was in reaction to Mary’s planned marriage to Philip II, the son of her cousin Charles V, and heir to the Spanish throne. Aside from opposing the marriage, the plans were not known in great detail, but one scheme was to have Elizabeth marry Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon, to ensure a native born succession to the throne. Elizabeth was once again under suspicion of treason. She denied any involvement or knowledge of Wyatt’s plans though several of Mary’s Councilors were determined to be rid of her. She was taken as prisoner to the Tower of London on Mary’s orders. Many had never returned from this place, including Elizabeth’s mother, and Elizabeth desperately declared her innocence.

Elizabeth was in a delicate and dangerous situation, where her life depended on the Queen’s orders. Her existence was a threat to her Catholic realm and Mary’s advisors urged her execution. The queen was reluctant, although this was not enough, as she had already succumbed to pressure to execute Lady Jane Grey against her will. Powerful persuasion would have led Mary to sign her sister’s death warrant, but multiple factors led to Elizabeth’s survival: lack of evidence against Elizabeth, Wyatt’s assurance that Elizabeth was innocent, and Elizabeth’s increasing popularity in the country. Instead of execution, Elizabeth was taken to the manor of Woodstock, near Oxfordshire, still as prisoner. Soon after Mary’s marriage to Philip, the queen believed she was pregnant, much to the joy of her Catholic supporters. A Catholic heir to the throne of England diminished hopes of a Protestant England and Elizabeth succeeding to the throne. A discouraged Elizabeth even reputedly considered escaping to France to avoid an imprisoned life.

Queen Elizabeth I

As the months passed, however, Mary’s pregnancy turned out to be nothing more than a phantom pregnancy and no baby would arrive. Philip left England for Flanders to attend to other political matters, leaving his devastated wife behind. The marriage of Philip and Mary was intended as a political match though Mary was reputed to have fallen in love with her husband. It was once again an opportunity for Elizabeth to observe a husband’s unloving treatment of his wife. Philip had departed in the summer of 1555 upon the abdication of his father’s throne and did not return until the spring of 1557, undertaking and flaunting his extramarital affairs before English diplomats in the meantime. At one point, Mary had removed one of her husband’s portraits from her sight and publicly declared “God sent oft times to good women evil husbands.” King Henry II of France even remarked from across the Channel, “I am of the opinion that ere long the king of England [as Philip was styled during their marriage] will endeavor to dissolve his marriage with the queen.”

Within months of his return, Mary believed herself to be pregnant again. However, no baby appeared a second time and this time, Mary was seriously ill. Without a natural heir, Elizabeth was still next in line for the English throne. Though she was Protestant, Philip was concerned that the next claimant after Elizabeth was the Queen of Scots, who was betrothed to the Dauphin of France, and so would fall into French hands. He even persuaded his wife that Elizabeth should marry his cousin to secure the Catholic succession, but Elizabeth refused to be a pawn for political gain.

Mary died on November 17, 1558, either of ovarian cancer or the influenza epidemic that plagued England at the time. Philip was already away when he heard of his wife’s passing and wrote, “I felt a reasonable regret for her death.”

No marriage

Elizabeth was now twenty-five years old and Queen of England. She was the last of the Tudor dynasty and therefore the pressure to marry and produce an heir was focused on from the moment of her succession. If Elizabeth died without a natural heir, many feared rival claims of Henry VII’s distant relatives would propel the nation into bitter civil war that had only ended upon the accession of the first Tudor monarch. The court was abuzz with suitors eager for her hand. European ambassadors busied themselves with marriage negotiations. Queen Elizabeth received offers from the King of Spain, Prince Erik of Sweden, The Archduke Charles, the son of John Frederic Duke of Saxony, The Earl of Arran, and Earl of Arundel, and Sir William Pickering. Only Elizabeth seemed uninterested in the subject of marriage. Over the years it was clear that the queen would never marry, instead “calling England her husband and her subjects her children.”

Political reasons begin with the complicated matter of a married female ruler as opposed to a male ruler. With the risk of childbirth that had already claimed the lives of two of Elizabeth’s stepmothers, the potential danger of a husband wanting to rule the country rather than being content with consort, a bitter struggle would ensue against various claimants. If Elizabeth married the heir to Spain or France, as already offered, England could have been absorbed into the Spanish Empire for example, losing English identity in the process. Her close relationship with the only man she ever loved, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was immersed in controversy and prevented a marriage from ever taking place. Protestant nations were generally poorer than Catholic ones at the time and alliances with other Catholic nations would have been a conflict of religion and very unpopular with her subjects and Council. Under English common law, a woman who married was the property of her husband and the possibility of sacrificing power to him must have appalled her.

From an early age and into her reign as Queen of England, Elizabeth had witnessed the subservience of women expected in Tudor times and the established pattern of bad marriages that plagued her family. By the time of her death in 1603, Elizabeth had ruled for 44 years and proved that a woman could rule as well as any man. Because of her, England started to become one of the most affluent and powerful countries in the world - and would remain so for centuries.