Ethics are moral principles that govern a person’s behavior in a society. In very simple terms, they constitute the rights and wrongs that guide people’s conduct. The Indian ethics are generally connected to the principle of anekantavada or many-sidedness, emphasizing that there is “no absolute truth” and no neatly defined binaries of right and wrong. They are based on factors such as the person practicing them, the situation, and the time at which they are practised. Indian ethics focus on accepting and encouraging diverse thoughts and beliefs, hence propagating “unity in diversity” and “diversity in unity.”

Apeksha Srivastava explains.

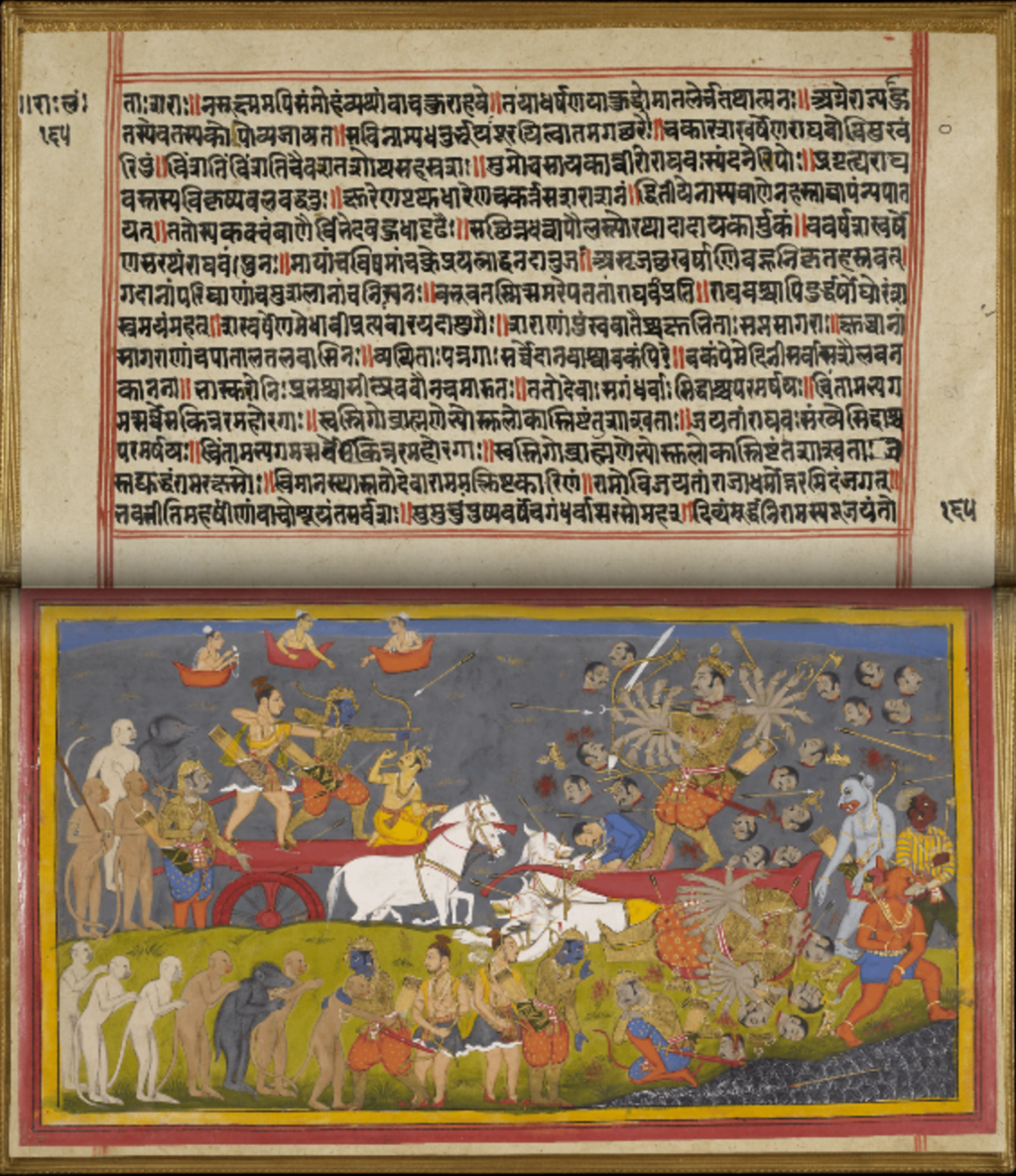

A manuscript from the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa. This shows Rāma slaying Rāvaṇa.

“It is surely extremely strange that whenever, either in Greek, or in Chinese, or in Persian, or in Arab writings, we meet with any attempts at describing the distinguishing features in the national character of the Indians, regard for truth and justice should always be mentioned first.” — F. Max Müller, Sanskritist and philologist (1882)

The Rig Veda and Upanishads

Composed between 1500–1000 BCE, the Rig Veda mentions the concept of Ritam (cosmic order) through which the physical and the social worlds are sustained. Ritam can be understood as the sense of righteousness. It later developed into the concept of Satyam (truth), with strong ethical implications. Dharma, the building block of Indian ethics, has been translated from the Rig Veda to refer to words such as justice, duty, righteousness, and order, among others. It is important to note that dharma is a multifaceted concept and does not denote a single idea or meaning.

Composed between 800 and 500 BCE, the Upanishads reveal further developments in Indian ethical thought. For example, Aham Brahma asmi (1.4.10; Brihadaranyaka Upanishad) translates to “I am Brahman (the Absolute)” and can be understood as: A person is a part of God (and not separate from this universal consciousness). It is essential to grow cognizant of this identity. Further, the Upanishads highlight that every person has a distinct nature (svabhava), function, truth, and path (svadharma), echoing the concept of anekantavada. The Puranas also propagate notions like all creation is interconnected and that one can be happy when all are happy.

Beyond Binaries

The Ramayana and Mahabharata stories underline the idea that ethics are complex. Several dilemmas shape the events of these epics and put forth the question: How to decide what is dharma in different situations? The central message of the Bhagavad Gita, part of the Mahabharata, is Nishkama Karma, meaning desireless action. It propagates the concept that people should work without any expectation of results. What matters ultimately is the inner growth of the individual, which can be achieved when one’s actions align with one’s dharma. Nishkama Karma forms the basis of Karma Yoga, a spiritual practice of selfless action that can lead a person to liberation (moksha). Lord Krishna emphasized that dharmacannot be practiced in passivity; several situations arise when a person needs to take a particular side in life. Some examples showcasing the sophisticated nature of dharma include the following:

Dronacharya: In the Mahabharata, Drona was a master of advanced military arts, including divine weapons. The Pandavas decided to use Drona’s only weakness, his son Ashwatthama, to save many lives in the war. The Pandava Bhima killed an elephant named Ashwatthama and spread the news of his death. Drona asked the Pandava Yudhishthira (known for always speaking the truth), who clearly said that Ashwatthama was killed. It is said that Krishna suppressed the word ‘elephant’ by blowing the conch. The news of the death of his son eventually led to the slaying of Drona. This story emphasizes that if an untruth saves lives, then perhaps ethics is not about always telling the truth.

Vibhishana and Kumbhakarana: Ravana’s brothers Vibhishana and Kumbhakarana in the Ramayana skillfully demonstrated that there is no single path to dharma and no single way of solving an ethical dilemma. Kumbhakarna adhered to the dharma of loyalty to his kin. At the same time, Vibhishana chose to follow the dharma of saving the people from the evil of his brother Ravana by opposing his kin and supporting Rama.

Buddhism’s Eightfold Path

Buddhism originated in the Indian subcontinent and mentions a noble eightfold path encompassing the ‘right’ vision, intention/aspiration, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. Once Buddha preached, “... whenever someone abuses us, we can either choose to accept or decline that anger. Our response will decide who owns and keeps the bad and negative feelings.” This story beautifully encourages the practice of the right speech, action, and mindfulness. Buddhism also talks about having compassion for others. Aligning with this idea, Buddhist economics studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods/services by changing the focus from self-interest to no-self (generosity), with ‘right’ livelihood and sustainability. While traditional economics emphasizes maximizing profits, Buddhist economics aims to minimize suffering (losses) for all.

Morals in Jainism

Jainism also originated in the Indian subcontinent and mentions the Triratna (three jewels) as the ‘right’ faith, knowledge, and walk. Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity), and aparigraha (Non-possession) are its five ethical codes. Detachment (non-attachment or non-possession) is one of its main morals. It can serve as the means to attain the realization of one’s self. Jainism’s concept of violence, acceptable only when absolutely necessary for self-defense, appears to echo with Lord Krishna’s advice from the Mahabharata that dharma cannot be practiced in passivity (at least, in certain situations according to Jainism).

The Timeless Classic

Composed around the 5th century CE by Thiruvallur and consisting of 1,330 short couplets, the Kural is a classic Tamil language text. It is considered a great work on morality, known for its secular nature. Some examples from this work include (a) In prosperity, bend low [be humble], (and) in adversity, stand straight [be strong], and (b) Always aim high—failure then is as good as success. This text provides worldly wisdom and guidance to make ethical decisions.

Some Case Studies on Different Aspects of Dharma

Din-i-Ilahi: The Divine Faith was propounded by the Mughal emperor Akbar (1582), who wanted to unite his people so that all of humankind could worship God according to their faith. Its writer, Abu’l-Fazl, expressed, “every sect can assert its doctrine without apprehension, and everyone can worship God after his own fashion.” Discriminations among the different religions of the realm were prohibited. Here, religious harmony emerges as a critical component of dharma.

The Story of Panna Dhai: I remember a story my mother told me during childhood. It is the tale of Panna Dhai, a 16th-century maid to Rani Karnavati, who helped her in political matters and the upbringing of the prince, Udai Singh II, along with her own son, Chandan. During the attack on Chittor, Panna sent Udai out to a river while putting her son in Udai’s place on the bed. When Bhanvir, the enemy, came and asked for Udai, Panna pointed at the bed occupied by her son and watched as Banvir murdered him. An epitome of courage and sacrifice, Panna adhered to the dharma of loyalty to her kingdom, where she lived. Saving the prince was more important to her than her child. This incident reflects anekantavada (“no absolute truth”) and dharma that depends on the person, situation, and time of practice. Panna chose her duty as a nursemaid over being a mother. Had she not done so, India might not have known the ancient hero Maharana Pratap, who was later born as the eldest son of Udai Singh II.

The Bishnoi Sacrifice: In the year 1730 at Khejadli (Rajasthan), 363 Bishnoi women, children, and men, led by Amrita Devi, sacrificed their lives to protect Khejadli trees while chanting their Guru’s teaching: “If a tree is saved even at the cost of one’s head, it is worth it.” It led the Maharaja of Jodhpur to prohibit tree cutting and animal hunting in all Bishnoi villages, attaching a sense of sacredness to these forms of nature. Such traditions from India are based on the dharmaof non-hurting and simple living.

Beyond One’s Life: Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856–1920) was a mathematics teacher, social reformer, and freedom fighter. He encouraged people to fight for India’s freedom so future generations could enjoy the fruit. It can be equated with thedharma of having no relaxation (in one’s efforts) so that one does not incur the curse of one’s children and descendants.

Guest is God: Indians have believed since ancient times in the spiritual tradition of guests being considered divine. Adhering to this principle as their dharma, many Taj Hotel employees died saving the lives of the hotel guests during the 26/11 Mumbai terrorist attacks. Although many knew all the back exits that could have safely led them out of the hotel, they stayed back to save the guests selflessly.

In conclusion, India’s ethics system is based on diverse philosophies, religious teachings, and cultural traditions spanning thousands of years. It is important to note that the information provided in this article is not exhaustive in nature. The complexity associated with ethics reflects India’s pluralistic society, offering insights into living a meaningful life. Understanding the anekantavada aspect of these ethics not only highlights India’s glorious past but also inspires discussions about morality in a rapidly changing world.

Apeksha Srivastava is pursuing her Ph.D. at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India. She was a visiting researcher at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs (USA) from April to July 2024.

References

Danino, M. (2020). System of ethics in India: Lecture and discussions. Perspectives on Indian Civilization course at IIT Gandhinagar.

Nadkarni, M.V. (2011). Ethics in Hinduism (Book – Ethics For Our Times: Essays in Gandhian Perspective). Oxford Scholarship Online.

Ganguli, K.M. (1883–1896). The fifteenth day at Kurukshetra – The fall of the preceptor, Drona (Mahabharata). Retrieved from wisdomlib.org.

Mahatthanadull, S. (2018). The noble eightfold path: The Buddhist middle way for mankind. International Buddhist Studies College, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University.

BBC. (2009). The three jewels of Jainism. BBC Religions.

Tiruvaḷḷuvar (around the 5th century CE). Tirukkural. Retrieved from wisdomlib.org.

Rajasthan Heritage Protection & Promotion Authority. (n.d.). Panna Dhai panorama, Kameri, Rajsamand. Rajasthan Government.

Spiegel, A. (2011, December 23). Heroes of Mumbai’s Taj Hotel: Why they risked their lives. NPR.