When conjuring up images of the First World War one may visualize the iconic and murderous trenches of the Western Front. Or perhaps the epic dogfights fought between intrepid pilots in rickety machines when aircraft was only in its infancy. But the global nature of the war witnessed fighting on a massive scale from the frigid waters of the North Sea to the scorching deserts of the Middle East and the mountains of the Alps where. In the Alps close to 700,000 Italians and half as many Austro-Hungarian (Habsburg) combatants would ultimately lose their lives in a brutal meat grinder in which combat was at times the not even the most dangerous contender.

Brian Hughes explains.

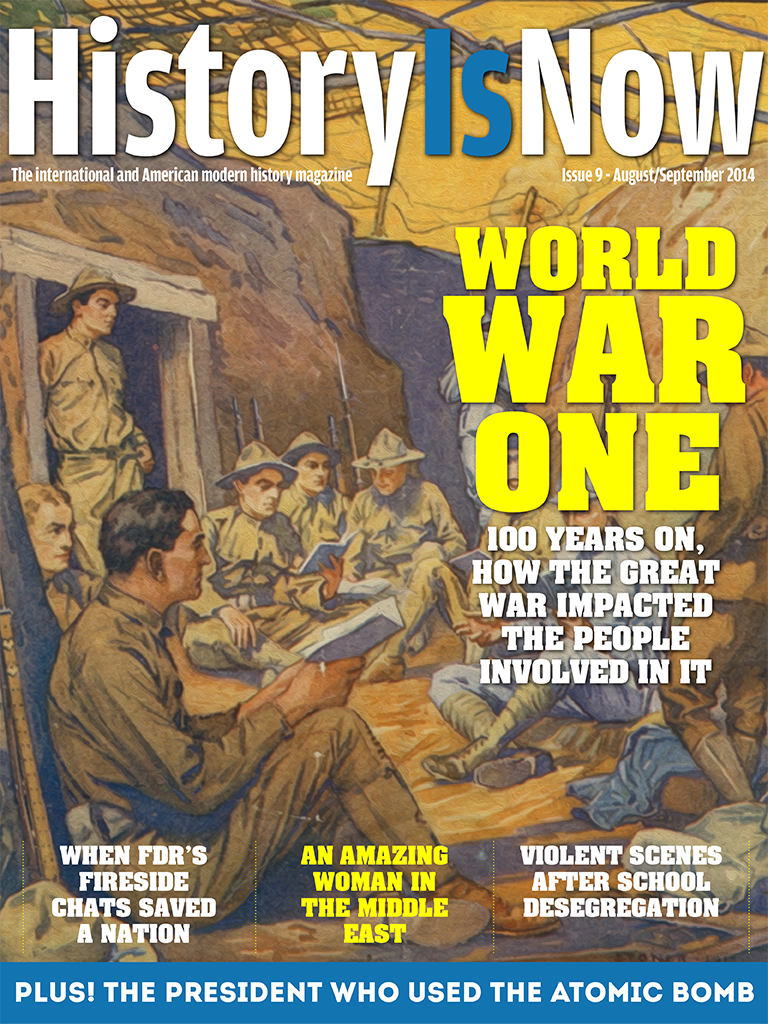

An trench of the Austro-Hungarian Army at the peak of the Ortler in 1917.

On May 23, 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary thus abandoning her initial neutrality. It had been nine months since the largest war in European history had begun, starting in August of 1914 when the other Great Powers of Europe, Great Britain, France, and Russia (The Entente) went to war against Germany and her ally Austria-Hungary (The Central Powers) in a complicated yet lethal system of alliances with one of the main aims of the Entente being to check the rising power of Germany on the continent. Italy, like the other belligerent nations, entered the war with the goal of “reclaiming” regions inhabited by Italian speaking peoples such as the Trentino in the Alps and Trieste on the Adriatic Coast, then in the possession of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Italy had only been unified as a cohesive nation in 1861, the first time in which they entire peninsula had coalesced under one government since the Roman Empire. The Entente hoped that by opening a brand-new front especially one so close to the heartland of Austria-Hungary would significantly relive the immense pressure in which the Central Powers had been administering to their foes in the Eastern and Western Fronts respectively.

Italy’s initial plan at the start of war was to begin a major offensive through the mountains of the Trentino in the Alps. Their objective was simple. Utilizing an overwhelming advantage in manpower the massive army would slice through the undermanned and poorly equipped Austro-Hungarian defenses like a hot knife through butter. Exploiting the gaps created by the enormous offensive thrust, the Italians would not only quickly retrieve the much sought-after Trentino region but simultaneously open roads to Ljubljana in present day Slovenia and Vienna, the Imperial Capital. But not everything went according to plan.

For starters, the Italian Peninsula is not ideally poised for offensive military operations to her northeast given that the mountain ranges of this region are amongst the highest in Europe. This gave the Austro-Hungarian defenders a significant advantage in that they could subsequently negate the numerically superior adversaries. Another factor was the lack of combat experience in the Italian Armed Forces. Prior to the outbreak of World War One Italy had fought a series of colonial wars in Africa against the Ottoman Empire. These engagements were comparatively small and drastically differed in men, material, and terrain now present on the Italian Front. This, combined with the outdated and draconian leadership within the Italian Army embodied especially by Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna would yield disastrous results. It seemed that the Italian High Command did not seem to notice or comprehend the brutality in which industrialized warfare enabled horrific carnage in France, Belgium, and the Eastern Front throughout the first year of the war. In addition to this, recent Central Power successes in Galicia enabled additional troops with valuable combat experience to be moved to the new front.

War at altitude

Prior to the 1984 Siachen dispute between Indian and Pakistani troops battles had for the most part never been waged in as high of altitudes such as in places like the Julian Alps of the Italian Front where peaks rise to an average height of 1300 meters. When fighting in these conditions an enemy’s bullet or stray shell could sometimes be less deadly than the environment itself. Soldiers had to contend with avalanches, rockslides, frostbite, freezing temperatures, and razor-sharp rocks to name just a few of the appalling hazards do not present in other theatres of the Great War. In order to tactically operate under these harsh conditions both Italian and Austro-Hungarian armies fielded units of specially trained Mountain soldiers who maintained the proper skills for conducting warfare in the mountains. The Alpini, on the Italian side were formed in 1872 and were the oldest “mountain corps” in the world. Recruited from the towns and villages along the Italian Alps, the Alpini were adept climbers, skiers, and hunters who were familiar with the latest innovations in mountaineering equipment and could sustain themselves for prolonged periods of time in hazardous mountainous surrounding as often they found themselves perched upon dangerous precipes and slopes in which they had to bivouac. The Habsburg Army confronted the Alpini with their own specially trained mountain corps knowns as the Alpen Kaiserjager. Like the Alpini, these men were recruited from mountainous regions throughout the Empire such as the Carpathians, Tatras, and Balkans. Heroic clashes and counter attacks between these elite units would become a trademark of the war.

The Isonzo (Soca) River Valley would become the major geographical focal point of the conflict, witnessing twelve major Italian Offensives all of which yielded horrific casualty rates. Once again, the Italian High Command did not seem to notice or even care about the difficulties exasperated by the terrain and poor quality of their troops. These murderous offensives would eventually culminate in October 1917 at the Battle of Caporetto, one of the deadliest battles of the Great War in which a combined Habsburg-German army valiantly resisted and ultimately routed a major offensive push by the newly equipped and colossal Italian Army. Caporetto would ultimately be the worst defeat suffered by the Italian Army throughout the war. Roughly 280,000 prisoners were taken in addition to the mass desertions of near 350,000 and some 40,000 killed or wounded.

Recovery

Despite these detrimental setbacks the Italians remarkably recovered. Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna would ultimately be sacked and was replaced with General Armando Diaz. The war would continue for another year until eventually the Habsburg Army who had held out for years undergoing unimaginable stress and demoralization from near constant shelling, hunger, cold, and the despair of losing friends and comrades would lay down their war weary arms. The last major chapter of the Italian Front occurred on October 23, 1918, in which finally a massive Italian artillery barrage accompanied by an equally formidable offensive finally routed the Austro-Hungarian army forcing an armistice on November 3rd, 1918.

World War One displayed loss of life and unimaginable suffering not yet seen in the course of human history. Despite the inconceivable numbers of men, animals, and materials lost the Italian theatre remains to this day one of the more obscure fronts as ultimately it became yet another stalemate in which old fashioned commanders ordered suicidal charges indifferent to the casualty rates just as on the more famous Western Front. The major difference being the terrain in which the soldiers fought. Instead of the mud in Flanders tit was the snows of the Alps where countless numbers of young men from all over Europe fought, died, and now rest under the placid valleys and dazzling peaks of one of the most beautiful corners of the continent.

What do you think of the Italian front in World War One? Let us know below.

Sources

Websites

Siachen dispute: India and Pakistan’s glacial fight - BBC News

Books

Gooch, John: The Italian Army and The First World War Cambridge University Press

Macdonald John: Caporetto And The Isonzo Campaign and Sword Military

Thompson Mark The White War Life and Death on The Italian Front 1915-1919 Basic Books