The story of rocketry stretches across centuries, blending ancient ingenuity with modern engineering on a scale that once seemed the stuff of myth. Its roots trace back to the earliest experiments in harnessing stored energy for propulsion, long before the word "rocket" existed. Ancient cultures such as the Greeks and Indians experimented with devices that relied on air or steam pressure to move projectiles. One of the earliest known examples is Hero of Alexandria's aeolipile, a steam-powered sphere described in the 1st century CE, which used escaping steam to produce rotation, a primitive but important precursor in the understanding of reactive propulsion.

Terry Bailey explains.

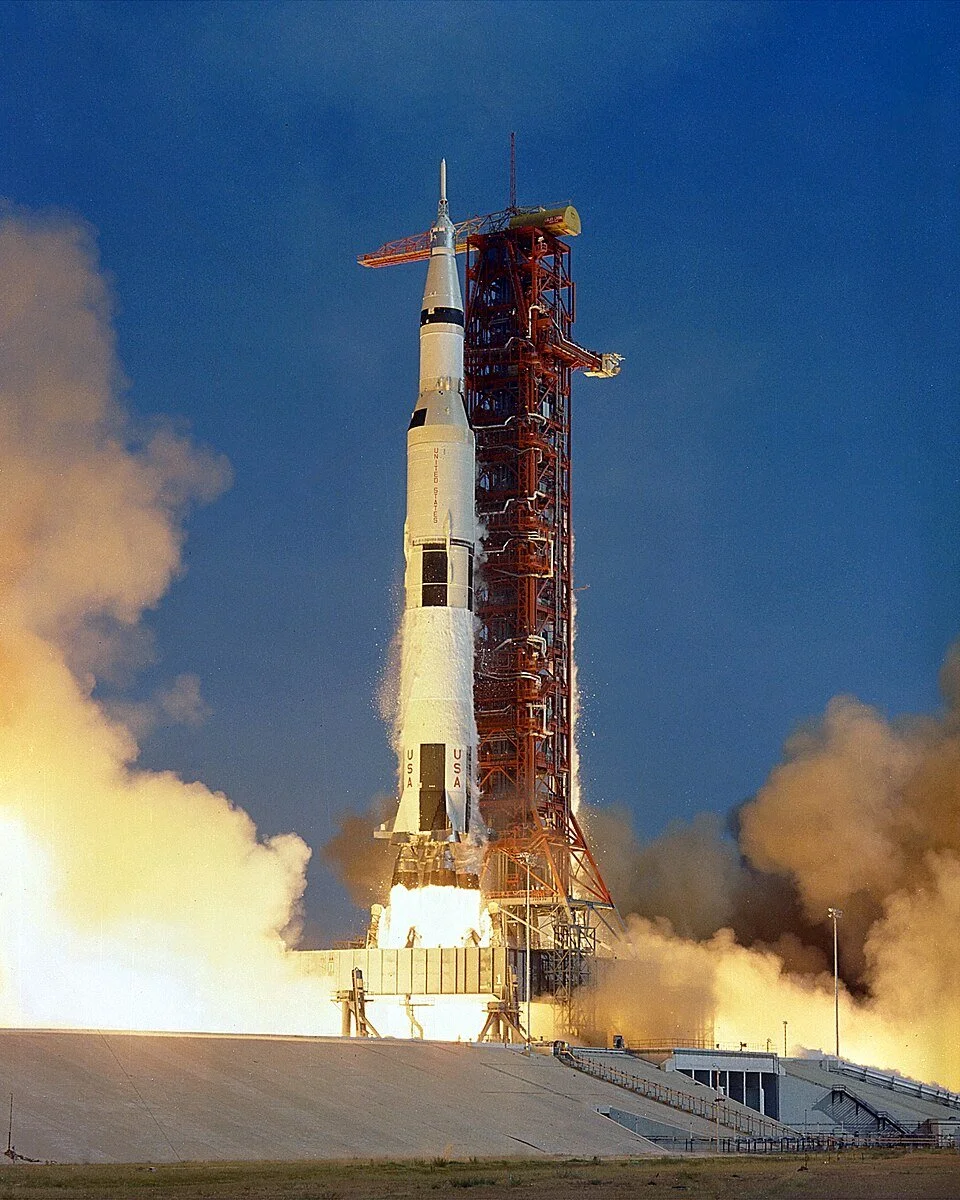

The Apollo 11 Saturn V rocket launch on July 16, 1969. The rocket included astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr.

While such inventions were more scientific curiosities than weapons or vehicles, they demonstrated the principle that would one day send humans beyond Earth's atmosphere: action and reaction. The true dawn of rocketry came in China during the Tang and Song dynasties, between the 9th and 13th centuries, with the development of gunpowder and a steady evolution. Initially used in fireworks and incendiary weapons, Chinese engineers discovered that a bamboo tube filled with black powder could propel itself forward when ignited.

These early gunpowder rockets were used in warfare, most famously by the Song dynasty against Mongol invaders, and quickly spread across Asia and the Middle East. The Mongols carried this technology westward, introducing it to the Islamic world, where it was refined and studied. By the late Middle Ages, rockets had reached Europe, largely as military curiosities, though their accuracy and power remained limited.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, advances in metallurgy, chemistry, and mathematics allowed rockets to become more sophisticated. In India, the Kingdom of Mysore under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan developed iron-cased rockets that were more durable and powerful than earlier designs, capable of longer ranges and more destructive force. These "Mysorean rockets" impressed and alarmed the British, who eventually incorporated the concept into their military technology. William Congreve's adaptation, the Congreve rocket, became a standard in the British arsenal during the Napoleonic Wars and even found use in the War of 1812, immortalized in the line "the rockets' red glare" from the United States' national anthem.

However, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, rocketry began to move from battlefield tools to the realm of scientific exploration. Pioneers such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in Russia developed the theoretical foundations of modern rocketry, introducing the concept of multi-stage rockets and calculating the equations that govern rocket flight. In the United States, Robert H. Goddard leaped from theory to practice, launching the world's first liquid-fuel rocket in 1926. Goddard's work demonstrated that rockets could operate in the vacuum of space, shattering the misconception that propulsion required air. In Germany, Hermann Oberth inspired a generation of engineers with his writings on space travel, which would eventually shape the ambitions of the German rocket program.

It was in Germany during the Second World War that rocket technology made its most dramatic leap forward with the development of the V-2 ballistic missile. Developed under the direction of Wernher von Braun, the V-2 was the first man-made object to reach the edge of space, travelling faster than the speed of sound and carrying a large explosive warhead. While it was designed as a weapon of war, the V-2 represented a technological breakthrough: a fully operational liquid-fueled rocket capable of long-range precision strikes. At the war's end, both the United States and the Soviet Union recognized the strategic and scientific value of Germany's rocket expertise and sought to secure its scientists, blueprints, and hardware.

Saturn V

Through Operation Paperclip, the United States brought von Braun and many of his colleagues to work for the U.S. Army, where they refined the V-2 and developed new rockets. These engineers would later form the backbone of NASA's rocket program, culminating in the mighty Saturn V. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union, under the guidance of chief designer Sergei Korolev and with the help of captured German technology, rapidly developed its rockets, leading to the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit in 1961. The Cold War rivalry between the two superpowers became a race not just for political dominance, but for supremacy in space exploration.

The Saturn V, first launched in 1967, represented the apex of this technological evolution. Standing 110 meters tall and generating 7.5 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, it remains the most powerful rocket ever successfully flown. Built to send astronauts to the Moon as part of NASA's Apollo program, the Saturn V was a three-stage liquid-fuel rocket that combined decades of engineering advances, from ancient Chinese gunpowder tubes to the German V-2, to produce a vehicle capable of sending humans beyond Earth's orbit. It was the ultimate realization of centuries of experimentation, vision, and ambition, marking a turning point where humanity's rockets were no longer weapons or curiosities, but vessels of exploration that could carry humans to new worlds.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Extensive notes:

After Saturn 5

After the towering Saturn V thundered into history by carrying astronauts to the Moon, the story of rocketry entered a new era one shaped less by raw size and more by precision, efficiency, and reusability. The Saturn V was retired in 1973, having flawlessly fulfilled its purpose, but the appetite for space exploration had only grown. NASA and other space agencies began to look for rockets that could serve broader roles than lunar missions, including launching satellites, scientific probes, and crews to low Earth orbit. This period marked the shift from massive single-use launch vehicles to versatile systems designed for repeated flights and cost reduction.

The Space Shuttle program, inaugurated in 1981, embodied this philosophy. Technically a hybrid between a rocket and an airplane, the Shuttle used two solid rocket boosters and an external liquid-fuel tank to reach orbit. Once in space, the orbiter could deploy satellites, service the Hubble Space Telescope, and ferry crews to space stations before gliding back to Earth for refurbishment. While it never achieved the rapid turnaround times envisioned, the Shuttle demonstrated the potential of partially reusable spacecraft and allowed spaceflight to become more routine, if still expensive and risky.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union pursued its heavy-lift capabilities with the Energia rocket, which launched the Buran spaceplane in 1988 on its single uncrewed mission.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, private industry began to take an increasingly prominent role in rocket development. Companies like SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk in 2002, pushed the boundaries of reusability and cost efficiency. The Falcon 9, first launched in 2010, introduced the revolutionary concept of landing its first stage for refurbishment and reuse. This breakthrough not only slashed launch costs but also demonstrated that rockets could be flown repeatedly in rapid succession, much like aircraft. SpaceX's Falcon Heavy, first flown in 2018, became the most powerful operational rocket since the Saturn V, capable of sending heavy payloads to deep space while recovering its boosters for reuse.

The renewed spirit of exploration brought about by these advances coincided with ambitious new goals. NASA's Artemis program aims to return humans to the Moon and eventually establish a permanent presence there, using the Space Launch System (SLS), a direct descendant of Saturn V's engineering lineage. SLS combines modern materials and computing with the brute force necessary to lift crewed Orion spacecraft and lunar landers into deep space.

Similarly, SpaceX is developing Starship, a fully reusable super-heavy rocket designed to carry massive cargo and human crews to Mars. Its stainless-steel body and methane-fueled Raptor engines represent a radical departure from traditional rocket design, optimized for interplanetary travel and rapid turnaround.

Other nations have also stepped into the spotlight. China's Long March series has evolved into powerful heavy-lift variants, supporting its lunar and Mars missions, while India's GSLV Mk III carried the Chandrayaan-2 lunar mission and is preparing for crewed flights. Europe's Ariane rockets, Japan's H-II series, and emerging space programs in countries like South Korea and the UAE all contribute to a growing, competitive, and cooperative global space community.

The next generation of rockets is not only about reaching farther but doing so sustainably, with reusable boosters, cleaner fuels, and in-orbit refueling technology paving the way for deeper exploration. Today's rockets are the culmination of more than two millennia of experimentation, from ancient pressure devices and Chinese gunpowder arrows to the Saturn V's thunderous moonshots and today's sleek, reusable giants.

The path forward promises even greater feats, crewed Mars missions, asteroid mining, and perhaps even interstellar probes. The journey from bamboo tubes to methane-powered spacecraft underscores a truth that has driven rocketry since its inception: the human desire to push beyond the horizon, to transform dreams into machines, and to turn the impossible into reality. The age of exploration that the Saturn V began is far from over, it is simply entering its next stage, one launch at a time.

The development of gunpowder

The development of gunpowder is one of the most transformative moments in human history, marking a turning point in warfare, technology, and even exploration. As outlined in the main text its origins trace back to 9th-century China, during the Tang dynasty, when alchemists experimenting in search of an elixir of immortality stumbled upon a volatile mixture of saltpetre (potassium nitrate), sulphur, and charcoal.

Instead of eternal life, they had discovered a chemical compound with an extraordinary property, it burned rapidly and could generate explosive force when confined. Early records, such as the Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe (c. 850 CE), describe this "fire drug" (huo yao) as dangerous and potentially destructive, a warning that hinted at its future military applications.

Needless to say, by the 10th and 11th centuries, gunpowder's potential as a weapon was being fully explored in China. Military engineers developed fire arrows, essentially arrows with small tubes of gunpowder attached, which could ignite and propel themselves toward enemy formations. This led to more complex devices such as the "flying fire lance," an early gunpowder-propelled spear that evolved into the first true firearms.

The Mongol conquests in the 13th century played a critical role in spreading gunpowder technology westward, introducing it to the Islamic world, India, and eventually Europe. Along the way, each culture adapted the formula and experimented with new applications, from primitive hand cannons to large siege weapons.

In Europe, gunpowder arrived in the late 13th century, likely through trade and warfare contact with the Islamic world. By the early 14th century, it was being used in primitive cannons, fundamentally altering siege warfare. The recipe for gunpowder, once closely guarded, gradually became widely known, with refinements in purity and mixing techniques leading to more powerful and reliable explosives.

These improvements allowed for the development of larger and more accurate artillery pieces, permanently shifting the balance between fortified structures and offensive weapons.

Over the centuries, gunpowder would evolve from a battlefield tool to a foundation for scientific progress. It not only revolutionized military technology but also enabled rocketry, blasting for mining, and eventually the propulsion systems that would send humans into space. Ironically, the same quest for mystical transformation that began in Chinese alchemy led to a discovery that would reshape the world in ways those early experimenters could never have imagined.

The spread of gunpowder

The spread of gunpowder from its birthplace in China to the rest of the world was a gradual but transformative process, driven by trade, conquest, and cultural exchange along the vast network of routes known collectively as the Silk Road. As outlined it was originally discovered/developed during the Tang dynasty in the 9th century, gunpowder was initially a closely guarded secret, known primarily to Chinese alchemists and military engineers.

Early references describe how gunpowder became a standard component of military arsenals, powering fire arrows, exploding bombs, and early rocket-like devices. The Silk Road provided the ideal channels for such knowledge to move westward, carried by merchants, travelers, and most decisively armies.

The Mongol Empire in the 13th century became the major conduit for the transmission of gunpowder technology. As the Mongols expanded across Eurasia, they assimilated technologies from conquered territories, including Chinese gunpowder weapons. Their siege engineers deployed explosive bombs and primitive cannons in campaigns from China to Eastern Europe, and in doing so exposed the Islamic world and the West to the potential of this strange new powder.

Along the Silk Road, not only the finished weapons but also the knowledge of gunpowder's ingredients, saltpetre, sulphur, and charcoal, were transmitted, along with basic methods for their preparation. These ideas blended with local metallurgical and engineering traditions, accelerating the development of more advanced weaponry in Persia, India, and beyond.

By the late 13th century, gunpowder had firmly taken root in the Islamic world, where scholars and artisans refined its composition and adapted it for use in both hand-held and large-scale firearms. Cities like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo became hubs for the study and production of gunpowder-based weapons. At the same time, Indian kingdoms began experimenting with their designs, leading eventually to innovations like the iron-cased rockets of Mysore centuries later. From the Islamic world, the technology moved into Europe, likely through multiple points of contact, including the Crusades and Mediterranean trade. By the early 14th century, European armies were fielding crude cannons, devices whose direct lineage could be traced back to Chinese alchemists' experiments hundreds of years earlier.

The Silk Road was more than a route for silk, spices, and precious metals, it was a pathway for the exchange of ideas and inventions that altered the trajectory of civilizations. Gunpowder's journey along these trade and conquest routes transformed it from an obscure alchemical curiosity in China into one of the most influential technologies in world history, fueling centuries of military innovation and eventually enabling the rocketry that would take humanity into space.