In the golden age of experimental flight during the Cold War, one aircraft tore through the boundaries of both speed and altitude, becoming a bridge between atmospheric flight and the vast, airless domain of space. That aircraft was the North American X-15. A rocket-powered research vehicle with the appearance of a sleek black dart, the X-15 was not merely a machine, it was a bold hypothesis in motion, testing the very limits of aeronautics, human endurance, and engineering. In many ways, it was the spiritual forefather of the Space Shuttle program and an unsung hero in the early narrative of American space exploration.

Terry Bailey explains.

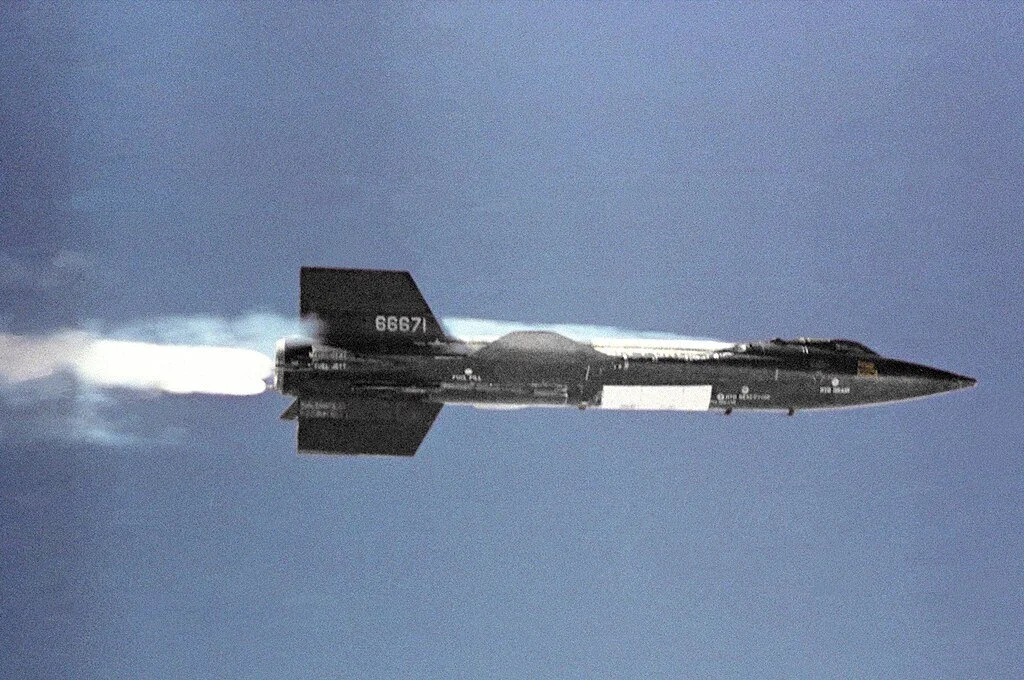

The X-15 #2 on September 17, 1959 as it launches away from the B-52 mothership and has its rocket engine ignited.

The X-15 was born of a collaboration between NASA's predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the United States Air Force, and the Navy. With Cold War tensions fueling aerospace rivalry and technological innovation, the goal was clear: to develop an aircraft capable of flight at hypersonic speeds and extreme altitudes, realms where conventional aerodynamics gave way to the unknown. Built by North American Aviation, the X-15 made its first unpowered glide flight in 1959 and quickly entered the history books as one of the most important experimental aircraft ever constructed.

At its heart, the X-15 was an engineering marvel. Its airframe was constructed from a heat-resistant nickel alloy called Inconel X, designed to withstand the immense frictional heat generated at speeds above Mach 5. Unlike typical jet aircraft, the X-15 was carried aloft under the wing of a modified B-52 Stratofortress and then released mid-air before firing its rocket engine, the Reaction Motors XLR99, capable of producing 57,000 pounds of thrust. With this power, the X-15 reached altitudes beyond 80 kilometers, (50 miles), and speeds exceeding Mach 6.7 (over 7242 KM/h, (4,500 MP/h)), achievements that placed it at the cusp of space and earned several of its pilots astronaut wings.

Among those pilots was a young Neil Armstrong. Before he became a household name for his historic moonwalk, Armstrong was a civilian test pilot with NASA and a central figure in the X-15 program. He flew the X-15 seven times between 1960 and 1962, pushing the envelope in both altitude and velocity. One of his most notable flights was on the 20th of April, 1962, which ended with an unintended high-altitude "skip-glide" re-entry that took him far off course. This event showcased both the perils of high-speed reentry and the need for advanced control systems in near-spaceflight conditions. Armstrong's calm response under pressure during this incident earned him admiration from peers and superiors, and further solidified his credentials as a top-tier test pilot.

Setbacks

The program was not without setbacks. The most tragic moment occurred on the 15th of November, 1967, when Air Force Major Michael J. Adams was killed during flight 191. The X-15 entered a spin at over 80 Kilometers, (50 miles), in altitude, and due to a combination of disorientation and structural stress, the aircraft broke apart during re-entry. Adams was posthumously awarded astronaut wings, and the accident triggered intense analysis of high-speed flight dynamics and control. It also underscored the razor-thin margins of safety at the frontiers of human flight.

Despite the dangers, the X-15 program accumulated a trove of invaluable data. Throughout 199 flights, pilots and engineers learned critical lessons about thermal protection, control at hypersonic velocities, pilot workload, and reaction to low-atmosphere aerodynamic conditions. Much of this information would later prove crucial in designing vehicles capable of surviving re-entry from space, including the Space Shuttle. While the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs relied on vertical rocket launches and capsule splashdowns, the Space Shuttle envisioned a reusable spacecraft that could land on a runway like an aircraft. That concept had its conceptual roots in the flight profiles and engineering solutions first tested with the X-15.

The transition from aircraft-like spacecraft to traditional rockets during the height of the space race had more to do with political urgency than technological preference. After the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik in 1957 and Yuri Gagarin's orbit in 1961, the United States found itself in a heated contest for national prestige. Rockets could deliver astronauts into orbit more quickly and more reliably than any air-launched spaceplane. Capsules like those used in the Mercury and Apollo programs were simpler to design for orbital flight and could survive the rigors of re-entry without complex lifting surfaces or pilot guidance. Speed, not elegance or reusability, became the watchword of the race to the Moon.

Groundwork

Nevertheless, the X-15 quietly laid the groundwork for what would eventually become NASA's Space Transportation System (STS)—the official name for the Space Shuttle program. Many of the aerodynamic and thermal protection system designs, including tiles and wing shapes, were informed by the high-speed test data gathered during the X-15's decade-long tenure. Perhaps most importantly, the X-15 proved that pilots could operate effectively at the edge of space, with partial or total computer control, a vital step in bridging the gap between conventional flying and orbital spaceflight.

By the time the X-15 made its final flight in 1968, the world's attention had turned to the Moon. The Apollo missions would soon deliver humans to the lunar surface, eclipsing earlier programs in public imagination. But engineers, planners, and astronauts alike never forgot the lessons learned from the X-15. It wasn't just a fast plane; it was a testbed for humanity's first real stabs into the boundary of space, a keystone project whose legacy can be traced from the chalk lines of the Mojave Desert to the launchpads of Cape Canaveral.

Today, the X-15 holds a unique place in aerospace history. While it never reached orbit, it crossed the arbitrary border of space multiple times and tested conditions no other aircraft had faced before. It provided the scientific community with data that could not have been obtained any other way in that era. And it trained a generation of pilots, like Neil Armstrong who would go on to make giant leaps for mankind. In the lineage of spaceflight, the X-15 was not a detour, but a vital artery, one that connected the dream of spaceplanes to the reality of reusable spaceflight. Without it, the Space Shuttle might never have left the drawing board.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the legacy of the X-15 is far more profound than its sleek, black silhouette suggests. It was not just an aircraft, but a crucible in which the future of human spaceflight was forged. Operating at the outermost edges of Earth's atmosphere and at speeds that tested the boundaries of physics and material science, the X-15 program served as a proving ground for the principles that would underpin future missions beyond Earth. Every flight, successful or tragic, added a critical piece to the puzzle of how humans might one day travel regularly to space and return safely. It demonstrated that reusable, winged vehicles could operate at the edge of space and land on runways, a notion that would become central to the Space Shuttle program.

Though overshadowed by the spectacle of the Moon landings and the urgency of Cold War politics, the X-15's contributions quietly endured, embedded in the technologies and methodologies of later programs. Its pilots were not only test flyers but pioneers navigating an uncharted realm, and its engineers laid the groundwork for spacecraft that would carry humans into orbit and, eventually, toward the stars. In many ways, the X-15 marked the beginning of the transition from reaching space as a singular feat to treating it as an operational frontier.

As we look ahead to a new era of space exploration, where reusable rockets, spaceplanes, and even crewed missions to Mars are no longer science fiction, the lessons of the X-15 remain deeply relevant. It stands as a testament to what is possible when ambition, courage, and engineering excellence converge. In the story of how we reached space, the X-15 was not merely a stepping stone, it was a launchpad.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Notes:

Neil Armstrong

Neil Armstrong was an American astronaut, aeronautical engineer, and naval aviator best known for being the first human to set foot on the Moon. Born on the 5th of August, 1930, in Wapakoneta, Ohio, Armstrong developed a fascination with flight at an early age and earned his pilot's license before he could drive a car. After serving as a U.S. Navy pilot during the Korean War, he studied aerospace engineering at Purdue University and later joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor of NASA. His work as a test pilot, especially flying high-speed experimental aircraft like the X-15, showcases his calm demeanor and technical skill.

Armstrong joined NASA's astronaut corps in 1962 and first flew into space in 1966 as commander of Gemini 8, where he successfully managed a life-threatening emergency. His most famous mission came on the 20th of July, 1969, when he commanded Apollo 11 and made history by stepping onto the lunar surface. His iconic words, "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind," marked a defining moment in human exploration.

Alongside fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin, Armstrong spent about two and a half hours outside the lunar module, collecting samples and conducting experiments, while Michael Collins orbited above in the command module.

After the Apollo 11 mission, Armstrong chose to step away from public life and never returned to space. He taught aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati and later served on various boards and commissions, contributing his expertise to space policy and safety.

Known for his humility and preference for privacy, Armstrong remained a symbol of exploration and achievement until his death on the 25th of August, 2012. His legacy endures not only in the history books but also in the inspiration he continues to provide to generations of scientists, engineers, and dreamers.