Politicians have a history of using fear to gain votes and win elections. Here, Jonathan Hennika (his site here), follows on from his first article on Scared America (here) and considers recent events in the US in the context of 19th century America. He explains how Chinese immigration to America, particularly to California, led to hostility and the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which would significantly reduce Chinese immigration.

A sketch on the ship Alaska, bound for San Francisco, with many Chinese people aboard. Sketch from Harper’s Weekly in 1876. Available here.

Something unexpected happened as an outcome of the Watergate Scandal: Americans realized their leaders were merely human. When transcripts from the Oval Office tape recording system utilized by Nixon became available, the populace was shocked to hear their President say to his Chief of Staff: “You know, it's a funny thing. Every one of the bastards that are out for legalizing marijuana is Jewish. Whatthe Christ isthe matter with the Jews, Bob? What is the matter with them? I suppose it is because most of them are psychiatrists.”[i]

President Donald Trump has further demystified and possibly demoralized the Office of the President. In an Oval Office meeting with Congressional leaders, discussing protecting immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador, and some African nations, the President asked, "Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?"[ii]

Immediately upon taking office in January 2017, President Trump signed an Executive Order[1]banning immigration from certain Middle East countries. The purpose of the Order was laid out in the first paragraph:

The visa-issuance process plays a crucial role in detecting individuals with terrorist ties and stopping them from entering the United States. Perhaps in no instance was that more apparent than the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when State Department policy prevented consular officers from adequately scrutinizing the visa applications of several of the 19 foreign nationals who went on to murder nearly 3,000 Americans. And while the visa-issuance process was reviewed and amended after the September 11 attacks to better detect would-be terrorists from receiving visas, these measures did not stop attacks by foreign nationals who were admittedto the United States.[iii]

According to a Fact Sheet issued by the State Department, “For the next 90 days, nearly all travelers, except U.S. citizens, traveling on passports from Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Iran, Somalia, Libya, and Yemen will be temporarily suspended from entry to the United States.”[iv]

Despite many legal challenges and additional Executive Orders issued by President Trump, some form of this travel ban remains in effect. Numerous raids by the aptly acronymic ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) have stormed businesses and stalked illegal immigrants at non-immigration related court hearings. No one is safe from deportation, including military veterans.

These actions are just part and parcel of the American experience. Nor is this the first timethat our leaders enacted laws barring the immigrant population from becoming part of the American Narrative.

RISE OF THE ‘YELLOW PERIL’

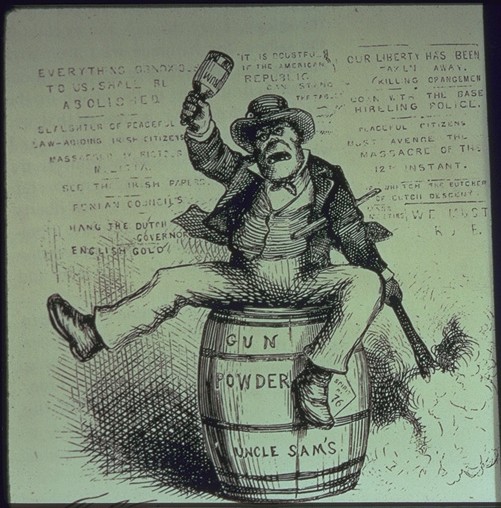

`They are coming to take our jobs,’ is an oft-repeated refrain when speaking of any significant numbers of want-to-be immigrants. From the Irish of the 1850s to the Latinos of the 1980s, and somewhere in between, there is the Chinese. The 47thUnited States Congress has the ignominious distinction of being the first to codify discrimination based upon national origin. The signature piece of legislation: The Immigration Act of 1882, historically referred to as the Chinese Exclusion Act.

In similar fashion to the Know Nothing Party, decades later in California,there was a political party with nativist roots. Founded in 1877, the California Workingman’s Party took control of the state legislature in 1878. In their session in Sacramento, they rewrote the State’s Constitution, disenfranchising the Chinese. In an address that same year, Denis Kearney, founder of the CWP, declared, the Chinese “are imported by companies, controlled as serfs, worked like slaves, and at last go back to China with all their earnings. They are in every place; theyseem to have no sex. Boys work, girls work; it is all aliketo them.” Kearney used inflammatory rhetoric, stating that “we shall arm” and “we are men, and propose to live like men in this free land, without the contamination of slave labor, or die like men, if need be, in asserting the rights of our race, our country, and our families.[v]

The Chinese first began emigrating to the western coast of the American continent after the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1849. In the decade of the 1850s, over 40,000 Chinese immigrants entered the United States. In the next decade,that number increased to close to 65,000.[vi]A majority of that population settled in California.

The Chinese Exclusion Act

When discussing the motivation of any group of immigrants, there are two factors: pull and push. Pull factors are the concepts, ideas,ormonetary reward for moving to a new nation. In this example, the California Gold Rush was the first pull factor for the Chinese. An additional pull factor was the plentiful jobs working on the construction of the first transcontinental railroad. By the early 1860s, in response to the rise of the Chinese immigrants, the State of California enacted legislation heavily taxing these cheap "coolie" laborers, the "Anti-Coolie” tax.

Push factors, on the other hand, are intolerable conditions in the native homeland of the immigrant group. The potato famine of the 1840s drove many Irish and Germans away from their ancestral homes. In the 1850s China was engulfed in the Taipei Rebellion, a quasi-religious Civil War that raged from 1850 until 1864. There are estimates that 20 to 30 million Chinese lost their lives during the Rebellion, not counting those that died due to disease and famine in the aftermath. The Taipei Rebellion served as a significant push factor in the Chinese immigration to the United States.

Political pressure mounted on Congress to act on the immigration issue. California continued to place prohibitions on Chinese immigration, but it was not enough, a national solution was required. On August 3, 1882, President Chester Arthur signed the Immigration Act into law. In bowing to the California pressure groups and the national labor movement, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred any additional skilled or unskilled labor from entering the country. There were exceptions for professional Chinese immigrants such as doctors and lawyers though. The Immigration Act of 1882 was modified in 1888 by the Scott Act, which stated any Chinese in the United States who returned toChina were no longer permitted re-entry intothe United States. Set to expire in 1892, Congress enacted the Geary Act, re-authorizing the Immigration Act of 1882, for ten years. In 1902 the Geary Act was renewed but did not set an expiration date.

Judicial Discretion: Chae Chan Ping v United States, 130 US 581 (1889)

The judicial branch must make any test of law enacted by the legislative branch, in accordance withthe wishes of the Founders when they created the conceptual idea of a separation of powers. In a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court declared the Chinese Exclusion Act constitutional. The Plaintiffin the case was Chae Chan Ping, who challenged the validity of the Chinese Exclusion Act on the ground it violated the Treaty of Wangxia. Signed in 1844, the Treaty of Wangxia was the American equivalent of the Anglo-Chinese Treaty of Nanjing, which ended the First Opium War in China. The relevant section of the treaty guaranteed unlimited entry of Chinese to America. Writing for the majority, Justice Horace Grey stated, “The power of the government to exclude foreigners from the country whenever, in its judgment, the public interests require such exclusion, has been asserted in repeated instances, and never denied by the executive or legislative departments.” The justice questioned the legal standing of the Plaintiff. Concluding that “If there be any just ground of complaint on the part of China, it must be madeto the political department of our government, which is alone competent to act upon the subject.” [vii]

An analogy: The majority of the Supreme Court told Mr. Chae, “Sorry, sir, that’s not my department, let me see if I can find someone for you.” The Legislative Branch passed a law based upon the "threat" represented by the incoming Chinese. The Executive Branch, in all its 19thCentury feckless glory, signed the Bill into Law. The Judicial Branch, eight white men (Stephen J. Field, Joseph P. Bradley, John Harlan, Horace Gray, Samuel Blatchford, Melvin Fuller, David Brewer, Henry Brown, andLucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II), ratified the law. The Chinese Exclusion Act finally ended in 1943, when the United States and China became wartime allies.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

You can read more of Jonathan’s work at Portable Historian: www.portablehistorian.com.

[1]An Executive Order is a rule or order issued by the President to the Executive Branch, bypassing the legislative branch, and having the full force and effect of law.

[i]https://www.thoughtco.com/richard-nixon-quotes-2733879

[ii]Josh Dawsey. “Trump Derides Protections for Immigrants From ‘Shithole’ Countries.” The Washington Post(January 2018) https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-attacks-protections-for-immigrants-from-shithole-countries-in-oval-office-meeting/2018/01/11/bfc0725c-f711-11e7-91af-31ac729add94_story.html?utm_term=.0abfecb37af0

[iii]President Trump. “Executive Order: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States.” (2017) https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/27/donald-trump-executive-order-immigration-full-text

[iv]Homeland Security. “Fact Sheet: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry to the United States.” (January 29, 2017) https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/01/29/protecting-nation-foreign-terrorist-entry-united-states

[v]Dennis Kearney, President, and H. L. Knight, Secretary, “Appeal from California. The

Chinese Invasion. Workingmen’s Address,” Indianapolis Times, (28 February 1878).

[vi]Immigration to the United States, “History of Immigration, 1783-1891,” http://www.immigrationtounitedstates.org/549-history-of-immigration-1783-1891.html

[vii]CHAE CHAN PING v. the UNITED STATES 130 U.S. 581(9 S.Ct. 623, 32 L.Ed. 1068)https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/130/581