Nearly exhaustive research has been done on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s (FDR’s) four national campaigns, his controversial Presidency, and his leadership in WWII. Surprisingly little, however, has focused on his New York State gubernatorial campaign in 1928. This was the campaign and position in which FDR would prove his fitness for the presidency of the Unites States, a position he held from 1933 to 1945.

In part 3, K.R.T. Quirion tells us about Roosevelt’s opponent, Albert Ottinger, and then how Roosevelt performed on the campaign trail.

You can read part 1 on how Roosevelt overcame a serious illness, polio, to be able to take part in the 1928 campaign here, and part 2 on how Roosevelt accepted the nominarion here.

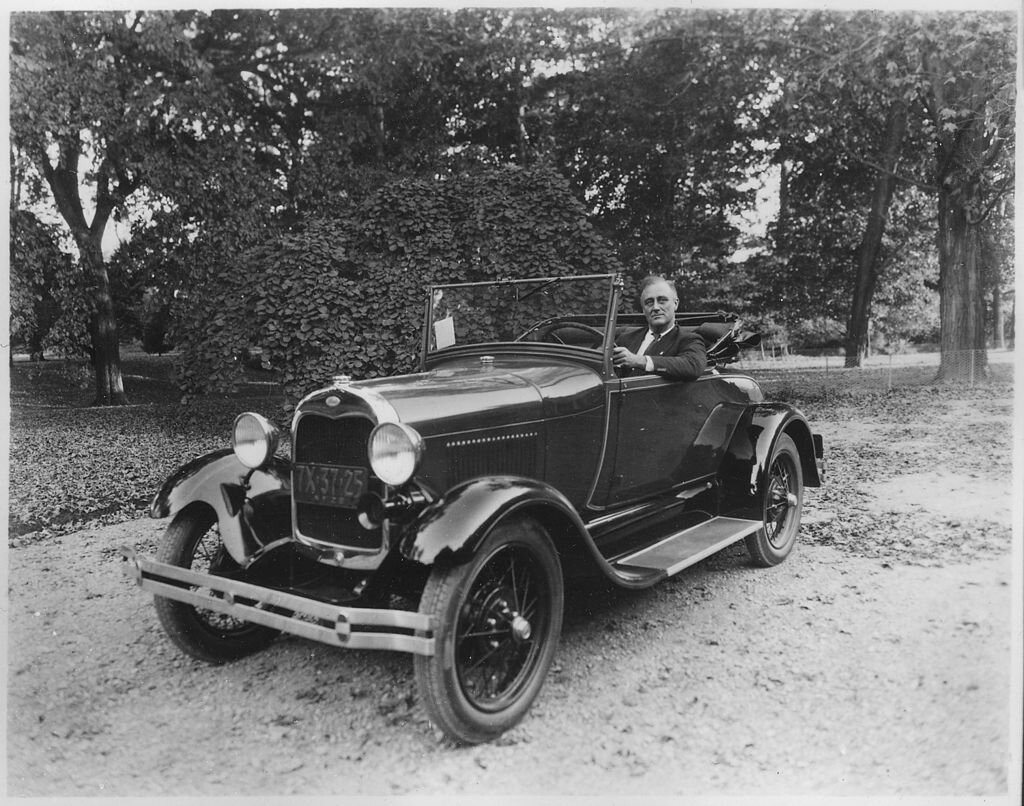

Franklin D. Roosevelt in Hyde Park, New York in 1928.

THE OPPOSITION

Like Roosevelt, Albert Ottinger had an impressive resume. A graduate of New York University School of Law, Ottinger was elected to the State Senate of New York in 1917 and 1918. In 1921 he was appointed Assistant Attorney General of the United States. Three years later he resigned from this position and was elected Attorney General of New York. He was re-elected in 1926 as the sole survivor of a Democratic landslide. That year every other member of the Republican ticket went down in defeat.[1] Roosevelt knew that Ottinger was a “very promising gentleman” as well as a serious political opponent.[2]

In an early interview with S.J. Woolf of the New York Times, Ottinger said that, “[t]he inhibitions, ‘thou shalt not lie’ and ‘thou shalt not steal,’ would perfectly describe the work upon which I have been employed throughout my term of office as Attorney General, and I shall continue to employ them in my future work.”[3] He also took the opportunity to tout his record of fighting for the common man. Ottinger recalled how, when a statute requiring voting machines to be installed throughout New York City was being debated, he had fought for the enforcement and protection of each citizen’s right to vote, and for that vote to “be honestly counted.”[4]

He claimed that he was for the honest enforcement of all State laws, including those deemed harsh, archaic or repressive. Tempering these remarks, he said that there is a humane manner to accomplish the execution of a law. Where a law is humane it must be “humanely interpreted and applied.”[5] As an example, he pointed to his work with the Workmen’s Compensation act.[6] By clearing out backlogged cases as Attorney General, Ottinger claimed to have granted quick relief to the maimed. Furthermore, his fight against loan sharks, grafters, and other types of criminal fraud enabled him to campaign as a “champion of ‘little people.’”[7]

Besides accepting Roosevelt’s challenge to make the water-power policy a primary issue of the race, Ottinger used his nomination speech to reveal other parts of his platform. He focused on minimizing the “extravagant expenditures of Smith’s administration. In its place, he pledged to focus on the economy, revise the taxation system and “abolish the State income tax.”[8] He also announced his intent to establish a state bureau of investigation to “detect crime and discover the criminal.”[9]Finally, he vowed to stamp out corruption in state and local governments.[10] On the prohibition question Ottinger—unlike Roosevelt—decided to stay silent.

Ottinger waged an active campaign throughout the State. Beginning with his acceptance speech in NYC on October 16, Ottinger spoke sixteen times in fourteen up-state cities before returning to Manhattan on the 24th.[11] Early on he associated himself with Herbert Hoover and the wider national election. At his first stop in Elmira, NY, Ottinger told the crowd that he believed the people of New York would “Hooverize [the] election…and…draft the brains of that gigantic genius of organization for…the benefit of all the American people.”[12] Political leaders up-State had assured him that “all those supporting Hoover would support [him].”[13] According to Oliver James, the Chairman of Ottinger’s campaign committee, the plurality of 600,000 up-State votes would decide the election.[14]

FROM BINGHAMTON TO POUGHKEEPSIE

Ottinger’s campaign men could make predictions of a massive up-State vote for their candidate because it was a historically Republican voting bloc. For that very reason, FDR chose to run a hard campaign in the up-State counties; whereas his Democratic predecessors had chosen to rely on their traditional bastions in the major cities. Instead, he had a theory for a new Democratic coalition of labor, agriculture, minorities, and urban voters. Seeking to forge this coalition, Roosevelt carefully crafted his platform with their interests in mind.

In Jamestown—a minor New York city but the heart of one of the States' most prominent agricultural centers, Chautauqua County—Roosevelt delivered his first message to the agricultural interests of the up-Staters’. After affirming the Democratic platform on agriculture, Roosevelt declared that he “aimed to go even further.”[15] He said that he wanted to see “the farmer and his family…put on the same level of earning capacity as their fellow Americans.”[16] Acutely aware that he was speaking in a primarily Republican district, he told the assembled crowd that his fight was “not with the Republican rank and file” but with the leadership.[17] Roosevelt had given a similar speech in Elmira—“the heart of dairy country”—the day before and was greeted by an audience that showed enthusiastically that they “appreciated his effort to deal constructively with their specific problems.”[18]

Roosevelt decided to roll out his labor plank in Buffalo on the 20th. He had originally planned to speak on a different subject but changed his plans when Ottinger “had the nerve to talk about what the Republican Party has done for labor.”[19] In Buffalo, Roosevelt delivered one of his most memorable lines from the campaign. “Somewhere in a pigeon-hole in a desk of the Republican leaders of New York State is a large envelope, soiled, worn, bearing a date that goes back twenty-five or thirty years.”[20] This envelope, he continued, has “Promises to labor” written on the front and is filled with identical sheets of paper dated two years apart.[21] “But nowhere is a single page bearing the title ‘Promises kept.’”[22] He closed by indicting “half-way measure[s]” proposed by a Republican “smoke-screen commission,” and challenged the crowd to compare the two party’s programs.[23]

Roosevelt then listed the Democrats’ promises to labor. First, he pledged to “complete Governor Smith’s labor and welfare program.”[24] Second, he promised to give old-age pensions a fair consideration.[25] He also guaranteed to establish an advisory board on minimum wage for women and children, extend the Workmen’s Compensation Act and liberalize “laws relating to the welfare of mothers and children.” [26] The Roosevelt administration would be committed to the principle that the “labor of human beings is not a commodity.” [27]

Social Programs

The next evening in Rochester, Roosevelt addressed the social programs that were central to the liberal platform of the New York Democratic Party. He began his discussion of these “human function[s]” of government by reminding voters of the great strides in education achieved by Governor Smith.[28] Despite the progress already made, FDR admitted that additional State aid would be needed to continue raising the minimum educational standards throughout the State.

Drawing a parallel between education and healthcare, he said that an expansion of medical service was needed statewide.[29]He lauded the Democratic Senate for passing bills increasing social welfare and government assistance but denouncing the Republican House for ignoring these “pleas” which they had “strangled to death in committee.”[30] If elected, he planned to accelerate the momentum already gained and ask for the money to expand healthcare assistance throughout the State.[31]

Finally, he addressed the issue of old-age pensions. New York’s great need for an old-age pension law was nowhere more apparent than when examining the State’s Poor Laws. In Rochester, he exclaimed that “[I]t just tears my heart to see those old men and women,” going into the County Poorhouse. [32] He concluded that if an adequate old-age law was passed there would be no need to reform the Poor Laws. Instead, they would be repealed “forever and ever.”[33] Roosevelt summarized all that he was trying to accomplish with his campaign by the motto, “Look outward and not in; look forward and not back; look upward and not down, and lend a hand.”[34]

From Water-power to Prohibition

The water-power issue was front and center in Syracuse. On the 23rd, he regaled the audience with the twenty-one-year long struggle between public and private power interests in the use and administration of water resources throughout the State. He weaved a complex narrative which portrayed the Republican Legislature as putting special interests above the good of the public, while the Democrats—and particularly Governor Smith—fought for the people of New York. He claimed that Ottinger’s election would mean the abandonment of the policy supported by the electorate.”[35] Worse still, it would mean the immediate abdication of power resources to “development by private corporations.”[36]

Syracuse turned out to be the most effective speech of the campaign.[37] This intense barrage forced Ottinger to address the issue on a battlefield of Roosevelt’s choosing. Ottinger explained his actions in terms designed to convince the electorate of his “profound devotion to the public interest.”[38] Even while Ottinger scrambled to cover his tracks on the power issue, FDR declared that the people had already made up their minds.

Later that same day in Utica, Roosevelt reiterated his stance against the re-enactment of State Prohibition Laws. Citing his tenure on the National Crime Commission, Roosevelt explained that all across the nation there was an “undoubted increase in crime.”[39] One factor contributing to this drastic crime surge was the bootlegging of liquor.[40] He expressed concern that Prohibition had caused a proliferation of criminal activity and was leading to a general disrespect for the law. In light of this, he appealed to the voters, urging them to fight the enactment of additional prohibition laws at the state level. He believed that state dry laws added to the confusion rather than streamlining enforcement. Instead, he believed that the Federal Volstead Act was sufficient—when properly enforced—to fulfill the needs of New York.

By the 26th, the campaign was seeing massive support from the up-State counties. Recounting his travels to a gathering in Troy, Roosevelt told how his motorcade was “kidnapped” in Fonda by a group of people in forty or fifty cars.[41] His abductors directed the campaign to the town of Gloversville. In past elections, “two Democrats, and sometimes three” went to the Gloversville polls on Election Day.[42] When Roosevelt arrived in the town, he was greeted by some two thousand people who had gathered to hear him speak. Later that same day the campaign made another impromptu stop in Amsterdam to speak before a group of sixteen hundred. “Too bad about this unfortunate sick man isn’t it,” he quipped.[43]

With the up-State tour complete, FDR returned to New York City with one week left of this fateful election.

Now, read the final part in the series, ‘Victory’, here.

What do you think of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s activity on the campaign trail? Let us know below.

[1] S.J Woolf, (1928, Oct 07), “The Two Candidates for the Governorship,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[2] “Roosevelt Demands State Keep Power,” 2.

[3] Woolf, “The Two Candidates for the Governorship,” 1.

[4] Ibid., 1.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ottinger explained that the Workmen’s Compensation act was a “beneficial statute passed in the interest of the injured workman.” Ibid.

[7] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 31.

[8] “Ottinger Accepts Power as Big Issue,” (Oct 16, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[9] Ibid, 2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Ottinger to Visit 14 Up-State Cites,” (Oct 13, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[12] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 3, 1928), “Ottinger Advances Queens Sewer Issue in Opening Campaign,” New York Times (1923-Current file), 1.

[13] “Big Ottinger Vote Predicted Up-State,” (Oct 12, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[14] “Ottinger to Visit 14 Up-State Cites,” 1.

[15] The platform included a “pledge for a careful study” of the farming economy and a pledge for an investigation into the “farm tax situation.” Roosevelt, “Extemporaneous Campaign Address (Excerpts), Jamestown, N.Y., October 19, 1928,” 27.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 29.

[18] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 19 1928), “Roosevelt Scouts Tariff Prosperity” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[19] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Buffalo, N.Y. October 20, 1928,” 30.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 30-31

[22] Ibid., 31.

[23] Ibid., 32.

[24] Ibid., 34-35.

[25] Ibid., 35.

[26] Ibid., 36.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Rochester, N.Y. October 22, 1928,” 38.

[29] Ibid., 41.

[30] Ibid., 42.

[31] Ibid., 41.

[32] Ibid., 43.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid., 44.

[35] Ibid., 50.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Davis, FDR: The New York Years, 42.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Utica, N.Y. October 25, 1928,” 51.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Troy, N.Y. October 26, 1928,” 54.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Big Ottinger Vote Predicted Up-State.” (Oct 12, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104441542?accountid=12085.

“F.D. Roosevelt Back; Sees Leaders Today.” (Oct 08, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104448848?accountid=12085.

F.D. Roosevelt Drive Will Start at Once; To Centre Up-State. (Oct 04, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104470038?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Choice of Roosevelt Elates Gov. Smith.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104308830?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 3, 1928). “Ottinger Advances Queens Sewer Issue in Opening Campaign.” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104425583?accountid=12085

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 18, 1928). “Roosevelt Assails Campaign Bigotry.” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104438214?accountid=12085

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 20, 1928). “Roosevelt Begins Work on Message.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104443997?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 24, 1928). “Roosevelt Confers on Labor Program.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104398916?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 11, 1928). “Roosevelt Hailed by South as Hope of Party in 1932.”New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104416279?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 19, 1928). “Roosevelt Scouts Tariff Prosperity” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104437219?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 22, 1928). “Roosevelt Stands Campaigning Well.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104310663?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 3, 1928), “Roosevelt Yields to Smith and Heads State Ticket; Choice Cheers Democrats,” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104308778?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Accepts Power as Big Issue.” (Oct 16, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104430730?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Concedes Roosevelt Victory.” (Nov 19, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104439338?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Refuses to Concede Defeat.” (Nov 08, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104415539?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger to Visit 14 Up-State Cites.” (Oct 13, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104460248?accountid=12085.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. “Acceptance Speech for the Renomination for the Presidency, Philadelphia, Pa.” June 27, 1936. The American Presidency Project. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15314.

“Roosevelt Attacks Theories of Hoover.” (Nov 02, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104414619?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Confers with Smith to Map Campaign in State.” (Oct 10, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104321497?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Demands State Keep Power.” (Oct 17, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104423627?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Opposes Any Move to Revive New York Dry Law.” (Oct 09, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104367563?accountid=12085.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Vol. 1, The Genesis of the New Deal 1928-1932. New York, NY: Random House. 1938.

“Roosevelt to Make Wide Tour of State.” (Oct 13, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104433007?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (1928, Oct 07). “Bigotry is Receding, Says F.D. Roosevelt.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/104469322?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Nov 27, 1928). “Democrats List Funds at Albany.” New York Times (1923-Current File).Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104304172?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Roosevelt Held Out to the Last Minute.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104326803?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Roosevelt Lauded by Mayor Walker.” New York Times (1923-Current File).Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104326338?accountid=12085.

Woolf., S.J. (1928, Oct 07). “The Two Candidates for the Governorship.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/104433929?accountid=12085.

Secondary Sources

Davis, Kenneth S. FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny 1882-1928. New York, NY: Random House. 1972.

__________. FDR: The New York Years 1928-1933. New York, NY: Random House. 1985.

Goldberg, Richard Thayer. The Making of Franklin D. Roosevelt: Triumph Over Disability. Cambridge, MA: Abt Books. 1971.

Gunther, John. Roosevelt in Retrospect, A Profile in History. New York, NY: Harper. 1950.

Troy, Gil, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and Fred L. Israel. History of American Presidential Elections: 1789-2008, Vol. II, 1872-1940. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2012.

Journal Articles

Carlson, Earland I. “Franklin D. Roosevelt's Post-Mortem of the 1928 Election.” Midwest Journal of Political Science, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Aug., 1964): pp. 298-308.

Goldman, Armond S., Elisabeth J. Schmalstieg, Daniel H. Freeman, Jr, Daniel A. Goldman and Frank C. Schmalstieg, Jr. “What was the cause of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s paralytic illness?” Journal of Medical Biography. (11, 2003): pp. 232–240.

Kiewe, Amos. “A Dress Rehearsal for a Presidential Campaign: FDR's Embodied "Run" for the 1928 Governorship.” The Southern Communication Journal. (Winter, 1999): pp. 154-167.