San Francisco is often considered to have a large homosexual community, something that statistics back up. But how long has there been a homosexual community in San Francisco? Here, Alison McLafferty tells us the history of the male homosexual community in San Francisco - and that it goes back a very long way.

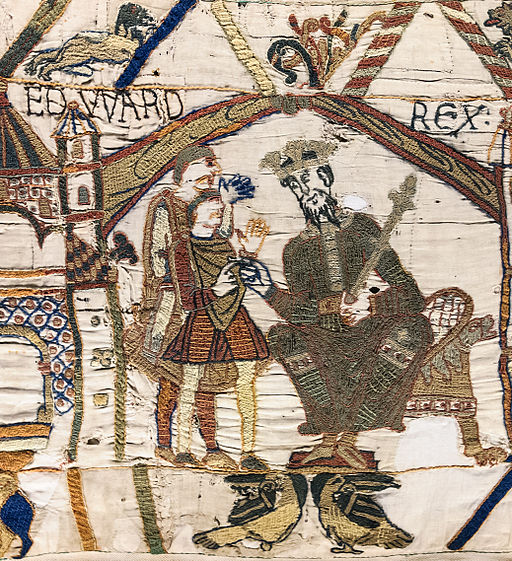

“The Miner’s Ball,” by Andre Castaigne, depicting a dance among during the 1849 California Gold Rush.

Ask almost anyone in the United States to list the first things that come to mind when they think of that glorious “City by the Bay,” San Francisco, and--along with exorbitant rent, candy-colored Victorian houses, and aging hippies-- they will invariably mention: “gay or homosexual men.”

The LGBT community in the Bay Area makes up 6.2% of the population, which is almost twice the national average of 3.6%. Homosexual men are also more numerous than homosexual women. The Castro neighborhood, the historic center of homosexual activity since the 1970s, is now one of the hubs of tourist activity. The streets are strewn with rainbow flags, and storefronts revel in double-entendres: “The Sausage Factory” is a restaurant and pizzeria, and “Hot Cookie” sells famously delicious cookies as well as--why not?--men’s underwear.

The city became a hub for homosexual activity in World War II, when men from all over the country found themselves in an all-male environment far from the families and small towns who knew and watched them closely. Facing an uncertain future and shrouded with the relative anonymity provided by a bustling urban hub, many sought to satiate previously hidden desires, finding solace in same-sex relationships. “I think the war has caused a great change,” one of the homosexual “Queens” in Gore Vidal’s 1948 novel, The City and the Pillar, mused while admiring a collection of marines and sailors at an all-male party. “Inhibitions have broken down. All sorts of young men are trying out all sorts of new things, away from home and familiar taboos.”

After the war, many men stayed in the city where they’d finally found a community that made them feel safe and welcome. When the “Summer of Love” bloomed in the Haight Ashbury district in 1967, wreathed in a haze of marijuana smoke and set to the rhythm of Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, and the Beatles, homosexual men joined in the general celebration of “free love.” The Castro Neighborhood right next-door to Haight Ashbury, with its cleaner streets, its large Victorian houses, and its cheap rent, became a mecca for homosexual men seeking to build their own community and culture.

So goes the usual history of homosexual men in San Francisco, but few people know that this story goes back much farther than this--back to the old Gold Rush days, back ever further to the days when the Miwok, the Ohlone, and the other Native American tribes hunted and fished in the wild coastlands of the Bay far before any foreigners arrived.

The Berdache

When French fur trappers, Spanish missionaries, and American explorers first encountered the Indian tribes of the Great Plains and the Pacific Coast, they were shocked to note the presence--in a wide variety of tribes--of Native American men who wore female clothing, performed female duties, and appeared to be the “wives” of prominent Native American men.

The generic term for such individuals became “berdache,” though different tribes had their own terms. The Hidatsa, for example (the tribe with whom Sacajawea was living when Lewis and Clark met her), called them“miáti.”The Lakota (the tribe led by Crazy Horse in the Battle of Little Bighorn against General Custer) called them “winkta.” Crazy Horse himself had a berdachein his harem. Such individuals existed in tribes from the Pacific Coast to the Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes-- but it was in California that the berdache were particularly ubiquitous.

Berdache were not considered “homosexual” by their tribes--Native Americans did not consider sexuality as binary as westerners came to do, nor did they consider it something biological. Instead, gender was considered an aspect of a person’s spirit, and berdache possessed both male and female spirits. They were not, however, intersex--or, to use the 19th century term, “hermaphrodites,” who possess both male and female biological characteristics. Berdache were biologically male, but often performed the roles of both men and women--for example, dressing as women but joining male war parties--in their daily lives, and generally had sexual relations and marriages with men.

Berdache were generally greatly respected by their tribes, as they were considered to be endowed with immense spiritual power: many were healers, medicine men, seers, and priests. But to the western missionaries and federal agents who encountered them, they were an abomination: something to be prayed over, forcefully dressed in men’s clothing, put to men’s work, and strictly punished.

The California Gold Rush

Such a severe crack-down was somewhat ironic: the same Europeans and Americans who exacted harsh punishments on the Native American berdache were quite blind to similar activities among their own people during the gold fever of the 1850s. As men of all ages, all races, and all nationalities flooded San Francisco’s harbor in their head-long rush for the gold fields of California, they found the city--and the newly minted state in general--a hotbed of homosexual activity.

Few men came to San Francisco specifically to seek out other men as sexual partners: the journey was long and arduous, fortunes were fickle, and the city itself was a hastily-built, slap-up affair that burned down every few years and featured, as one young man wrote in his diary, “Far too many drunken men lying in gutters.”

It also featured far too few women: gold digging was a male sport, something to be undertaken by the sex considered more adventurous, hardy, courageous and aggressive. Most men headed to San Francisco for the sole purpose of using it as a gateway to the gold fields: a place to grab some mining equipment, hitch a ride to the gold, strike it rich as soon as possible, and bring the fortune home to lure a lovely bride.

But the dearth of women-- the U.S. Census of 1850 set the population of non-Native women in the entire state of California at just 4.5%-- also provided opportunities for those who did have homosexual inclinations, who struggled with secret desires and new opportunities, or who claimed simple loneliness and the desire for any kind of company. Men who spent their days with their feet in the ice-cold waters of the American River and their backs bent double in the scorching sun sometimes spent their nights in camp with other men, sharing food, tents, and blankets. Starved for some fun and entertainment after long days in a stark, empty landscape, many headed to San Francisco in their free time, carefully hoarding the few flakes of gold they had managed to sift from the churning river waters.

Because there were never enough women to partner with all the men at dances, it was common practice for a man to tie a handkerchief to his upper arm to signify that he was willing to take the women’s role. Visitors to San Francisco remarked in bemusement on the spinning couples on dance floors-- shaggy, bearded men with faces scrubbed for the occasion, holding each other daintily about the waists, swaying gracefully, and dancing cheek to cheek. Some men even went so far as to don full gowns--often lent by amused prostitutes, who made up the majority of the population--and the practice was generally accepted.

The West, after all, was a space without the usual constraints of civilization: without the laws, taboos, and enforcement agencies that kept Victorian society tightly laced on the East Coast. It was a trans space in many ways--a space for crossing boundaries, lands, identities and sexualities. One Western gentleman (the records just name him “M”) who took several bullets fighting in the Indian Wars, explained that he dressed in women’s clothing because the petticoats covered the holes: “Then I forget all about them, as well as all other troubles,” he explained serenely.

The Third Sex

M, as well as other men of the West in general and San Francisco in particular, were tolerated in part because of the relative dearth of enforcement agencies, and in part because the people of that era understood homosexuality differently than people of the 20th or 21st century. The binary of “homosexuality” and “heterosexuality” did not exist until the 20th century, particularly with the rise ofFreud and his psychosexual theory of development. Freud claimed that humans are born innately bisexual, and that influences in early childhood determined whether or not they will follow a “straight” course of sexual development (heterosexual) or a “perverted” course (homosexual). Prior to the popularization of these ideas in the early twentieth century, society generally accepted the existence of a third group of people, commonly termed the “third sex.” This “third sex” was made up of men who identified themselves as women: they dressed as women, did women’s work, and had sexual relations with men. Colloquially, they were often termed “fairies.”

Although not fully accepted by society--and certainly not by religious institutions or law enforcement agencies--members of the “third sex” were usually tolerated, and even the police tended to leave them alone as long as they didn’t create too much trouble. This was due, in part, to the fact that they played an important role: in Victorian society, white women were considered to be chaste and even asexual, frightened and even repulsed by sex. In many urban centers such as New York City or San Francisco, then, women were not only sparse--as urban centers were considered public spaces where men congregated to work and play, keeping the women at home--but also sexually unavailable. This is one of the primary reasons prostitution was so rampant in the 19th century: prostitutes, themselves either perversions of womanhood or tragic “fallen” women, provided sexual outlets for men whose wives or girlfriends could not satiate their appetites.

Yet in some cases, such as in predominantly male working-class New York neighborhoods, or in Gold Rush San Francisco, even prostitutes were hard to find or too expensive. In those cases, many men sought out members of the “third sex. Because men in this era were thought to be inherently sexual (the constant production of sperm was cited as biological proof), a man who sought out sex was often considered “manly” no matter his choice in sexual partner. Manliness was therefore defined in part by sexual appetite--if no woman existed to slake it, a man might indeed seek out another man, particularly a member of the “third sex,” and no one would question either his manliness or his sexual orientation.

San Francisco, then, has almost always been a haven for homosexual men, in one way or another--and, contrary to popular belief, homosexuality has been historically tolerated across racial and geographic divides. The history of San Francisco’s homosexual community has often been presented as one of recent visibility and recent triumph--and it is true that the gains made since the Gay Liberation Movement of the 1960s-1980s have been momentous. Yet much of this history forgets the long tradition of men whose identities transcended the tenuous binary that 20th and 21st century society has imposed on both contemporary and past societies of different races. Understanding that the standards and codes by which we measure modern society are often of modern, western invention will help us to better understand the actions and experiences of historical subjects.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

Sources

U.S. Seventh Census 1850: California. [Accessed November 2018]: https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1850a-01.pdf

Gore Vidal, The City and the Pillar, (E.P Dutton & Co: New York, 1948).

Charles Callender, Lee M Kochens, “The North American Berdache,” Current Anthropology,Vol 24: No 4 (August-October 1983).

David Wishard, “Encyclopedia of the Great Plants,” Univeristy of Nebraska, Lincoln, 2011 [Accessed November 2018]: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.gen.004

Timothy C Osborne’s Diary, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

Albert Hurtado, Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California(University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 1999).

Susan Johnson, Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush(W. W. Norton & Company: New York, 2000).

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (Basic Books: New Yorkm 1995).

Barbara Weltman, “The Cult of True Womanhood,”American Quarterly, Vol. 18: No. 2, Part 1 (Summer, 1966).

Timothy Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 1994).

Frank Newport and Gary Gates, “San Francisco Metro Area Rates Highest in LGBT Percentage,” Gallup, March 20, 2015 [Accessed November 2018]: https://news.gallup.com/poll/182051/san-francisco-metro-area-ranks-highest-lgbt-percentage.aspx.

Peter Boag, Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past (University of California Press: Berkeley, 2011).

Brandon Ambrosino, “The Invention of Heterosexuality,” BBC, March 16, 2017 [Accessed November 2018]: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170315-the-invention-of-heterosexuality.