The pre-Enlightenment world was simultaneously both fascinating and frightening. People often ad no choice but to rely on their imaginations to make sense of the myriad phenomena around them. The result was a world where everything seemed magical; a place teeming with angels, demons, fairies, and witches. Only through uncanny and sometimes ‘ridiculous’ superstitions did many people of the Dark Ages (or Middle Ages or Medieval Period) in Europe try to make sense of their world. Jamil Bakhtawar explains.

The devil swapping a baby. Artist: Martino di Bartolomeo, 15th century.

The Lucky Horseshoe

There are reasons why people of the Medieval period believed that horseshoes were lucky. The first was that they were made of iron, a metal that was believed to ward off evil spirits. Another comes from the legend of Saint Dunstan in the 10th century. It was said that that Dunstan worked as a blacksmith and one day the Devil came into his shop. Dunstan pretended not to recognize him and went about getting horseshoes for the Devil’s horse.

However, instead of nailing the horseshoes to the horse, Dunstan nailed them to the Devil instead. The horseshoes caused the Devil immense pain but Dunstan said that he would only discard them if the Devil promised never to enter a home with a horseshoe on the door. The horseshoe was also believed to ward off witches and that is why it was believed that they rode on brooms. Therefore, it was said that a witch would be reluctant to enter any home with a horseshoe over the door. There were also rules regarding the horseshoe. The first was that it had to be iron, and the second was that it had to come off the horse on its own and not be taken off by any man. And then, the horseshoe would need to be nailed over the door with iron nails. There is some debate about the orientation of the horseshoe. Some believe that the horseshoe should point up so as to prevent the luck from spilling out of the horseshoe. Others believe that it should point down so that the luck can be poured upon those who enter the home.

The Royal Touch

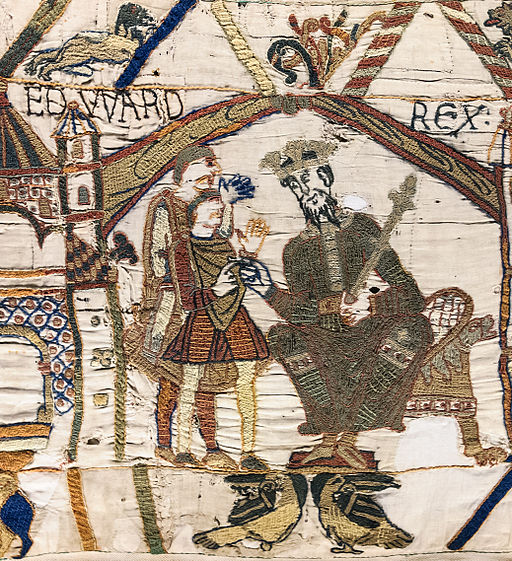

People often accepted that kings and queens, by virtue of their divine right to rule, had the power to heal disease by their touch. One particular malady called scrofula, a tubercular inflammation of the lymph glands in the neck, was believed to be healed when touched by a sovereign. This healing was seen as validation of the monarch’s appointment from God. It was claimed that the first to practice the healing touch was Edward the Confessor, ruler of England from 1042 to 1066.

In medieval times, grand ceremonies were held in which the ruler touched hundreds of people afflicted with scrofula, or the “King’s Evil.” These people then received special gold coins called “touchpieces” that they regarded as amulets.

Edward the Confessor as shown on the Bayeux Tapestry.

God Blesses After a Sneeze

One of the most well-known superstitions that is believed to come from the Middle Ages is the need to say, “bless you” after someone sneezes. There was a belief that sneezing gave Satan the opportunity to enter the body and the person who sneezed needed the help of God to exorcise the devil. Saying “God bless you” was believed to be a way to keep the Devil from entering the body and therefore save the person who had sneezed. It was a way to explain the death that sometimes occurred after a person sneezed and it instilled in people the sense that they could do something to help.

There was also the prevailing belief that a person could ’sneeze out their soul’. This was also counteracted by a person saying “God bless you” or covering the face to keep the soul in. This superstition was encouraged with the spread of illness during a time where there was little way to help people to overcome devastating ailments.

Spilling Salt

In the Middle Ages, salt was a precious resource, and it was believed to have medicinal properties. If salt was ever spilled, it was no longer able to be used for medicine and therefore it was gathered up and thrown over the left shoulder in order to blind the evil spirits that were said to constantly follow people around.

There is an even older reasoning behind the superstition that salt was known to make soil barren for an extended time, and this is the basis for the belief that spilling salt is akin to cursing the land.

Changelings

One prevalent superstition in Medieval Britain was the fear that a child could be taken and replaced with a changeling. One of the stories of the changeling comes from the tale of a blacksmith who noticed one day that his son suddenly became lethargic and was wasting away.

The blacksmith was told that his son was taken and replaced with a changeling. To prove it, he was told to put water into empty egg shells and place them around the fire. The child then sat up and spoke in the voice of the changeling stating that he had lived for centuries and had never seen something like that. The blacksmith then threw the changeling into the fire. The man journeyed into the land of the fairies with his bible and the fairies, unable to harm him due to the Bible, returned his son.

There were a number of unusual tests that people performed to try and see if their child was a changeling. They typically involved doing something so strange that it would draw the changeling out in surprise. One test was to place a shoe in a bowl of soup, and if the baby laughed it was a changeling. Also, making bread inside of egg shells was said to be so amusing to changelings that it would cause them to expose themselves. Some scholars have suggested that changelings may have been used as a way to explain autistic children, especially since the changes can come on quickly. When a child’s behavior and verbal skills rapidly declined or changed, it was blamed upon the doings of the changeling.

Magic and Witchcraft

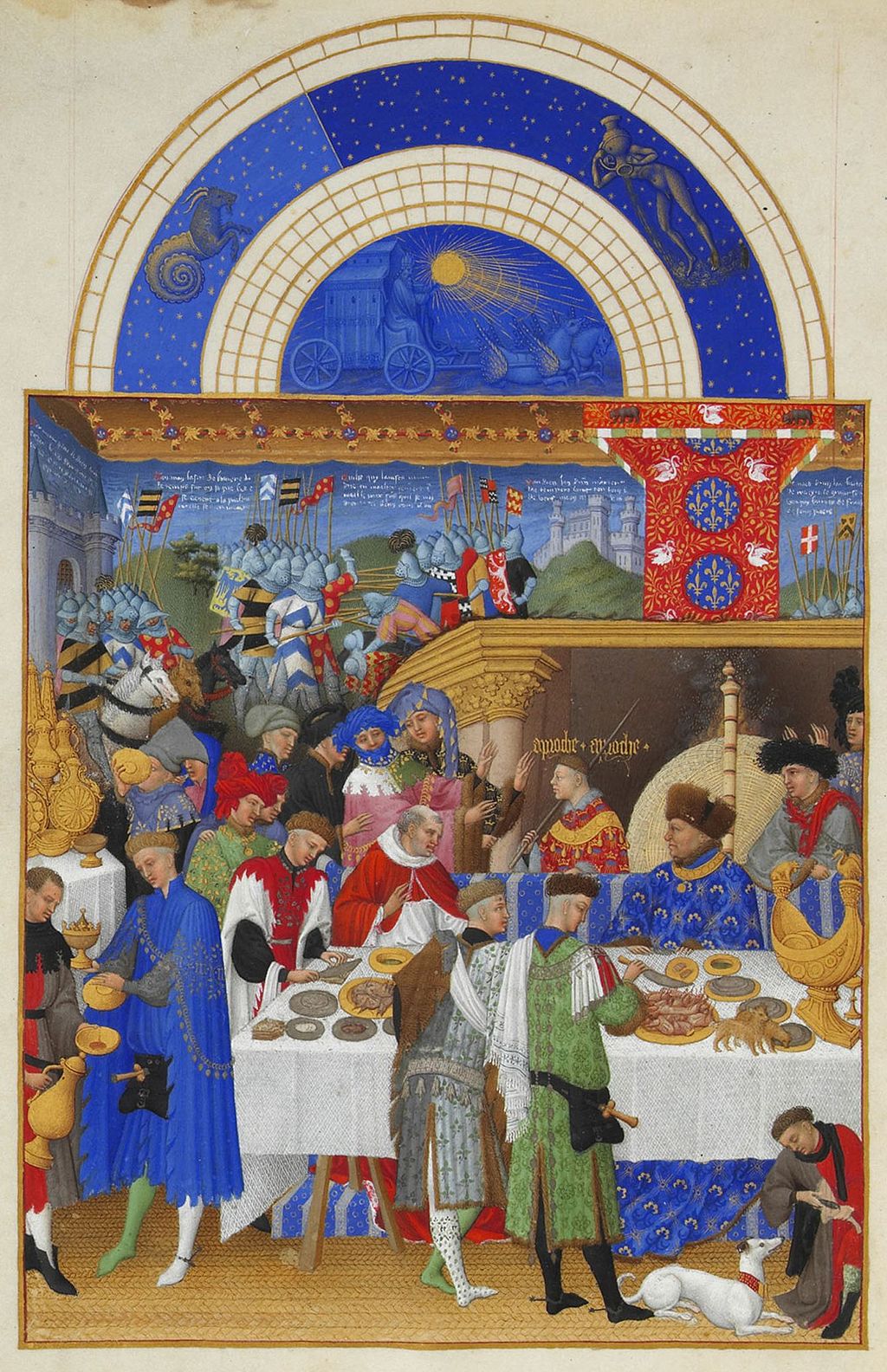

Throughout Europe, during the Middle Ages, belief in magic and sorcery was pervasive. Magic involved attempts to take advantage of ‘supernatural’ powers for personal benefit. A fascinating combination of magic and religion was involved in the lives of ordinary people and at times they would utilize spiritual practitioners who specialized in a multitude of beneficial magical services. Charms, prayers and rituals, which also incorporated some aspects of Christianity, were routinely employed in attempts to provide a diverse array of benefits. Also, this acted as a protective barrier against harmful magic, or maleficium, which was blamed for many of the hardships that plagued the European population during this period. For the most part, attempting to manipulate these powers was deemed superstitious by the religious establishment.

Consequently by the beginning of the 13th century, witchcraft in the Middle Ages began to be considered as ‘demonic-worship’ and was feared throughout Europe. People believed that magic represented Satan and was associated with devil worship. The types of magic that were said to be practiced during the Dark Ages were:

1. Black Magic

Black Magic was also known as the ‘harmful’ type of magic. Black Magic had more of an association with the devil and satanic worship. If someone fell ill of unknown causes, this was frequently said to be caused by witches who practice black magic. Other harms caused to society, such as accidents or deaths were also said to be caused by Black Magic.

2. White Magic

The basis of White Magic was Christian symbolism, and it focused on the power of nature and herbs. It was considered as the ‘good’ type of magic. White Magic was used for good luck, love spells, wealth and spells for good health. Astrology constituted another significant part of White Magic. Alchemy, which is the practice of making potions, was a part of White Magic as well.

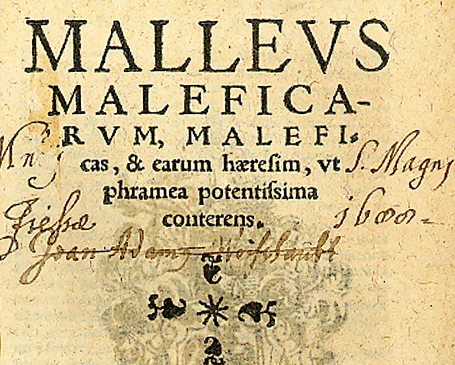

The 1486 book Malleus Maleficarum(often translated as the Hammer of Witches) decreed that witchcraft was heresy. It asserted that witches were mostly women and that female lust formed pacts with the Devil. Midwives were especially singled out for their alleged ability to prevent conception and terminate pregnancies. It accused them of eating infants and offering live children to the Devil. But the real heinousness of the Malleus Maleficarumwas in the procedures drawn up to identify and exterminate witches.

The accused were stripped and searched for the ‘devil’s marks’, then dunked in water or burned. Using the Malleus Maleficarumas a guide, torture was liberally used to extract confessions or implicate other people throughout the period witch hysteria. Gruesome torture devices were developed that could crush or dislocate bones, mangle bodily orifices and tear out fingernails. Red-hot pincers were applied to tear out pieces of flesh as well. Those found guilty of witchcraft were burned at the stake. All in all, there is no more damning testament to the dangers of superstition than the Malleus Maleficarum.

The cover of 1 1520 edition of the Malleus Maleficarum.

The Bride’s Garter

Bridal garments were considered blessed. The bride would have all her clothes ripped from her by the guests on the wedding night as everyone tried to snatch a piece. Gradually attention focused on the bride’s garter-ribbon – a symbol of sexuality and fertility.

In Medieval times, unmarried men fought for the bride’s garter to ensure they would be the next to find a beautiful and fertile wife. Bachelors even mobbed the bride as she stood at the altar, throwing her to the ground and ripping the garters from her during the wedding ceremony. When the church protested, the custom evolved to the groom removing the lucky garter from his new wife in the bridal chamber and tossing them down to the waiting men.

Number 13: A Troublesome Phobia

The belief that the number 13 is cursed primarily had a religious reasoning in the Middle Ages. For instance, there were 13 people who attended the Last Supper and therefore it was believed that 13 people at a gathering were a bad omen. Many believed that if a party was held for 13 people, whoever was the first to get up would be dead within the year.

With this superstition, people of the Dark Ages ensured there would never be 13 people gathered together. In fact, by the 16th century, it was claimed a person was a witch if they had 13 people together.

Conclusion

When one thinks of magic and superstitions of the Dark Ages, a number of assumptions and sometimes misguided beliefs come to mind. Witch hunts and superstitions caused many deaths and worried the minds of countless people. The world in which most Europeans lived involved belief in supernatural and mystical elements, over which humans could exert some influence with not only evil intentions and outcomes, but with good results as well. Although doing so was forbidden by the church, magical activities and beliefs were an integral part of the ordinary life of the people.

What Middle Ages superstitions do you know about? Let us know below.

Sources

http://www.thefinertimes.com/Middle-Ages/witches-and-witchcraft-in-the-middle-ages.html

Stuart Clark, “Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Culture,” in Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, ed, Bengt Ankarloo and Stuart Clark (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002),

Bailey, Magic and Superstition, 193.

https://hchroniclesblog.wordpress.com/2013/08/01/superstitions-of-medieval-england/

https://prezi.com/6caqxk-lpxhh/superstitions-of-the-medieval-times/