Jeb Smith recently read Larry Allen McCluney, Jr.’s book, The Paradox of Freedom: A History of Black Slaveholders in America. Here, he discusses his views of the book.

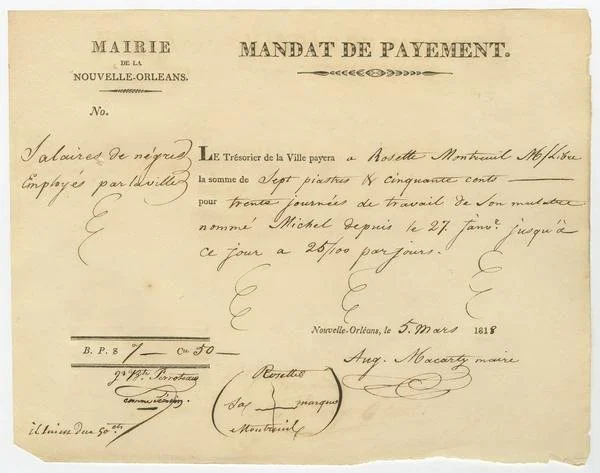

City of New Orleans, 5 March 1818. Order from the Mayor's office to the City Treasury to reimburse Rosette Montreuil, a free woman of color, for the work of her slave, Michel, "mulatto". Signed by mayor Augustin Macarty.

An Instructor of American History at Mississippi Delta Community College and an American Civil War Living Historian since 1995, Larry Allen McCluney received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history at Mississippi State University, and his research into original data for this book is extensive (he even utilized a History Is Now article). He cites and quotes many historians, as well as original sources, to bring to life a fact of American history: African Americans were slave owners too.

A mix of various “free peoples of color”—various mixed race and African Americans —owned people of their own race from colonial times up until after the Civil War. In some extreme cases slaves owned slaves. Some free African Americans even engaged in slave trading. This should not surprise us, as Africa has always been the center of slavery, where just as every other race in the world has been enslaved, and continues to enslave their own people. In fact, it was outside pressure from European nations that forced abolitionism on Africa.

African American slaveowners in America at times became some of the wealthiest planters and businessmen in the entire South. McCluney writes they became one with “the upper crust of the economic level in the pre-war South.” They entered into and at times mingled, intermarried, and associated with the white southern aristocratic class. These wealthy included many African American women.

For example, he quotes Steven J. Niven, who wrote of “Marie-Thérèse Coincoin, who lived for eight decades in Natchitoches Parish, La. She would help to found a family dynasty of Free, Colored planters, the Metoyers, who by 1830 owned over 200 slaves—8 percent of all enslaved people in the parish.” In Charleston City, South Carolina, 123 African American women owned slaves and were the “heads” of households, including Maria Weston, who by 1860 owned 14 slaves and owned property amounting to $40,000; the average white earned around $100. Marie Thérèse Metoyer of New Orleans owned around 11,000 acres of land, manufactured medicine, trapped animals, and grew tobacco.

Wealthy slave owners

Many African American slave owners owned hundreds or thousands of acres of land and were wealthier than the vast majority of whites. McCluney writes:

“In 1860, there were at least six free Blacks who owned 65 or more slaves. The largest number, 152 slaves, was owned by sugar cane planters, the widow C. Richards and her son P.C. Richards. Another slave magnate from Louisiana was Antoine Dubuclet, who owned over 100 slaves. He had an estate worth $264,000 in 1860 dollar value. This was in comparison with the wealth of White men of that time, averaging $3,978."

William Ellison Jr. of South Carolina, a free man of color, was one of the wealthiest plantation owners in the state. He was the largest slave owner in his area, with 171 slaves, and over 900 acres of land producing massive amounts of tobacco. He donated large sums of money and foodstuffs to the Confederate Army, offered the military 53 of his slaves, and his mixed race grandson fought in the Confederate Army.

Many of the slave owners were born in bondage but were later freed and, through either inheritance, gifts, or work ethic, improved their situation, eventually moving into the profitable business of slavery. It was not uncommon for free African Americans to own slaves. Thousands did so. According to the 1860 census, only 1.4% white people owned slaves in 4.8% of southern slave states, but 28% of free African Americans in New Orleans owned slaves. McCluney wrote, “In South Carolina, where forty-three percent of the free African American families owned slaves, the average number of slaves held per owner was about six. Similarly, in Louisiana, forty percent of free African American families owned slaves, twenty-six percent of those in Mississippi held slaves, twenty-five percent of those in Alabama, and this was also true for twenty percent of those in Georgia.”

Status

Their wealth elevated the status of these slaveowners of color, gaining them status among the highest in the white community, intermingling with, socializing, even marrying (even when it was illegal), and becoming some of the most well-respected people in their community. McCluney wrote of Justus Angel, born a slave in South Carolina but who became “a wealthy Black master who lived in Colleton District, South Carolina, in 1830. Angel was a plantation owner who owned 84 slaves, a staggering number even for a Black master. He was a man of great wealth and influence, which allowed him to amass such a large number of enslaved individuals under his control.” Of this wealthy planter class, he wrote, “These individuals often took steps to associate with the White elite, viewing themselves as an extension of this class. In doing so, the Black slaveowners were able to carve out a place for themselves within the ruling class.” Then there is William Johnson in Mississippi, who:

“Became a successful entrepreneur with a barbershop, bath house, bookstore, and land holdings. Though a former slave, in 1834 he would own three slaves and about 3,000 acres of property and would eventually own sixteen slaves before his death. He even hired out his slaves to haul coal and sand. Throughout his life, the white community in Natchez and Adams County held Johnson in high regard. He associated with and was close to many of Adams County’s most prominent white families. Following Johnson’s untimely death at the hands of a “free black, Baylor Winn, the Natchez Courier was moved to comment that Johnson held a “respected position [in the community] on account of his character, intelligence and deportment.”

Further, McCluney argues that it was the common opinion of slaves that African American masters made harsher masters, and they generally preferred white masters to their own color, for example, William Ellison had a reputation for harsh treatment of his slaves. One interviewed slave said, “You might think, master, dat dey would be good to dar own nation; but dey is not. I will tell you the truth, massa; I know I ‘se got to answer; and it’s a fact, they are very bad masters, sar. I’d rather be a servant to any man in de world, dan to a brack man. If I was sold to a brack man, I’d drown myself. I would dat—I’d drown myself! Dough I shouldn’t like to do dat; but I wouldn’t be sold to a coloured master for anything.”

Conclusion

Frederick Law Olmsted traveled south and told of the many wealthy African American planters he saw and interviewed a slave who said the African American masters “bought black folks, he said, and had servants of their own. They were very bad masters, very hard and cruel . . . If he had got to be sold, he would like best to have an American master buy him. The French [black Creole] masters were very severe, and ‘dey whip dar n****** most to deff—dey whipe de flesh off of ‘em.”

Far from abolitionists, these rich masters were reluctant to let their slave labor go as many whites had done. McCluney Quotes B. F. Jonas, of New Orleans who said “I have never heard of a case where a free African American owner of slaves voluntarily manumitted his slaves. On the contrary, they were as a rule considered hard task masters, who got out of their slave property all that they could.” And as has been recorded in Defending Dixie's Land, many of these southern masters supported the preservation of slavery and the continuation and protection of the Confederacy, to maintain bondage of their own brothers.

Jeb Smith is an author and speaker whose books include Defending Dixie's Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War written under the pen name Isaac C. Bishop, Missing Monarchy: Correcting Misconceptions About The Middle Ages, Medieval Kingship, Democracy, And Liberty and he also authored Defending the Middle Ages: Little Known Truths About the Crusades, Inquisitions, Medieval Women, and More. Smith has written over 120 articles found in several publications.