George Washington is often remembered as the figurehead of the American Revolution. The first President of the United States and Commander and Chief. His leadership was absolutely instrumental in our nation’s founding, his Presidency has continued to be seen as a guiding light among many leaders today. Yet, behind the image of a resolute commander and statesman lay a man who, after stepping down from power in 1797, faced a deep sense of anxiety and uncertainty over the future of the country he helped create. Far from basking in the glory of his achievements and historic relinquishing of power, Washington found himself haunted by doubts over the fragility of the new republic and his own role in the life of an ex-politician.

Preston Knowles explains.

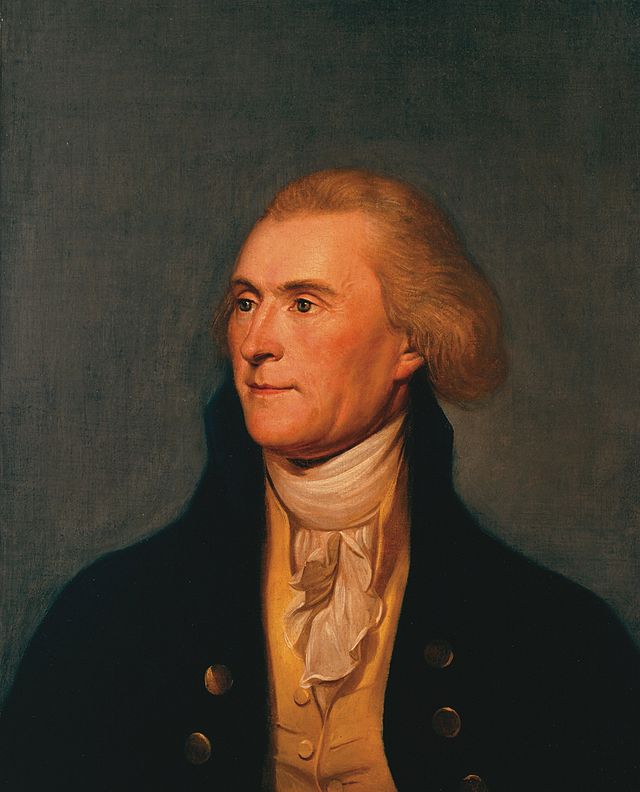

George Washington - The 1796 Lansdowne portrait.

The Man Behind the Legend

George Washington wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1796 “I am wearied by the public service.. But still am I anxious for the success of our republican experiment.” This quote would set the tone for his post-presidency years, a time where the founding father, despite his long known desire to retire, was deeply affected by the political divisions springing up in the youthful United States.

Washington’s desire to retire from public office wasn’t simply a political maneuver; it was a personal choice, Washington had long expressed his desire to return to Mount Vernon. And In his 1796 farewell address, Washington famously warned against “the spirit of the party,” describing it as a danger that could lead to the “destruction of the republic.” He cautioned against the divisiveness of political factions, understanding the potential for them to destabilize the unity of the nation.

Washington’s farewell address is one of the most enduring pieces of advice in American political history. Yet, despite his warnings, political parties emerged almost immediately after his departure of office. With Hamilton leading the Federalists on one side and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans on the other.

Washington held increasing concerns as these factions grew more hostile and entrenched. In his personal letters and conversations, he expressed frustration with the direction the country was taking. He feared that the growing divide would prevent the nation from achieving its potential and would ultimately lead to a breakdown in national unity. Even leading Washington to consider taking up public life again. In a letter to John Adams in 1796 he wrote,

“I have long been of the opinion that nothing but the most imperious necessity could ever call me to the helm again. I feel that we are in a dangerous situation, and I have no patience with the spirit of party that threatens to tear the country asunder.”

Seeking Peace, Finding Conflict

Washington’s post-presidency years at Mount Vernon were meant to offer him a chance to rest and return to a simpler life he had long dreamt of. He attempted to focus on the management of his estate. Yet, even in retirement, Washington was never truly free from the demands of public life.

His daily life at Mount Vernon was filled with a much loved routine: overseeing his land, attending to correspondence, and meeting with visitors. Washington's influence continued to loom large over the young nation. Presidents, legislators, and foreign leaders often turned to him for advice or reassurance. His very presence was a stabilizing force, and Washington’s judgment was still highly valued by those in power.

But even in the peaceful surroundings of his estate, Washington found himself troubled by the political turmoil that continued to roil the nation. Despite his desire to retire from public affairs, he remained a prominent figure, and his opinion was still sought after by those in power. In several letters in 1798 Washington frequently discusses his fear of the division the political parties were causing.

To John Jay in 1798, Washington reflected on the growing political conflict: “The party spirit has been carried to such lengths that it threatens to subvert the very government which it is supposed to protect.” These words, written from Mount Vernon, underscore his deepening anxiety about the emerging divisions within the government.

To Hamilton in 1798, Washington wrote, "I am fully persuaded that we have no alternative but to preserve the Union. Yet, how to do so, with the factionalism that is emerging, I cannot say.”

Washington’s letters to Jefferson were similarly filled with apprehension. In one, he lamented the growing ideological divide between the two men’s parties, saying, “It seems to me that we are drifting farther apart, and I fear the consequences of this estrangement.”

Despite his desire to avoid political involvement, Washington was repeatedly called upon to mediate disputes and offer guidance on ever evolving situations the Country faced. He was particularly concerned with the rise of foreign threats, particularly from France and Britain, and often expressed anxiety over how the country would navigate its position in the international arena.

In a letter to his friend James Madison, Washington wrote, “I tremble for the future when I think of our dependence on foreign nations. It is a great and dangerous experiment we have undertaken.” His thoughts on foreign relations reflected the weight of his concerns about the vulnerabilities of the young Republic, even in his retirement.

The Cost of Command

Despite his retirement, Washington found himself ever consumed by a longing sense of devotion to a nation he had given most of his life to serve. Finding himself ever worried over the turmoil the young country was facing, his anxieties speak to the immense pressures of leadership and the uncertainty even the most revered figures in history face when navigating the ever complex world of politics.

In the end, Washington did not find the peace he sought but he did provide an excellent and valuable lesson in the art of leadership, illustrating how even the most steadfast and stoic of leaders can be deeply affected by division and uncertainty. Spending his last years at Mount Vernon we see an often unseen side of Washington, not as the mythical figure of a revolutionary force. But as a man, whose doubt, worry and deep sense of responsibility weighed heavy on his mind through the last years of his life.

Did you find that piece interesting? If so, join us for free by clicking here.