Here, we look at the story of Captain William Kidd, His Lovely and Accomplished Wife Sarah, and Pirate Mythology. Samuel Marquis explains.

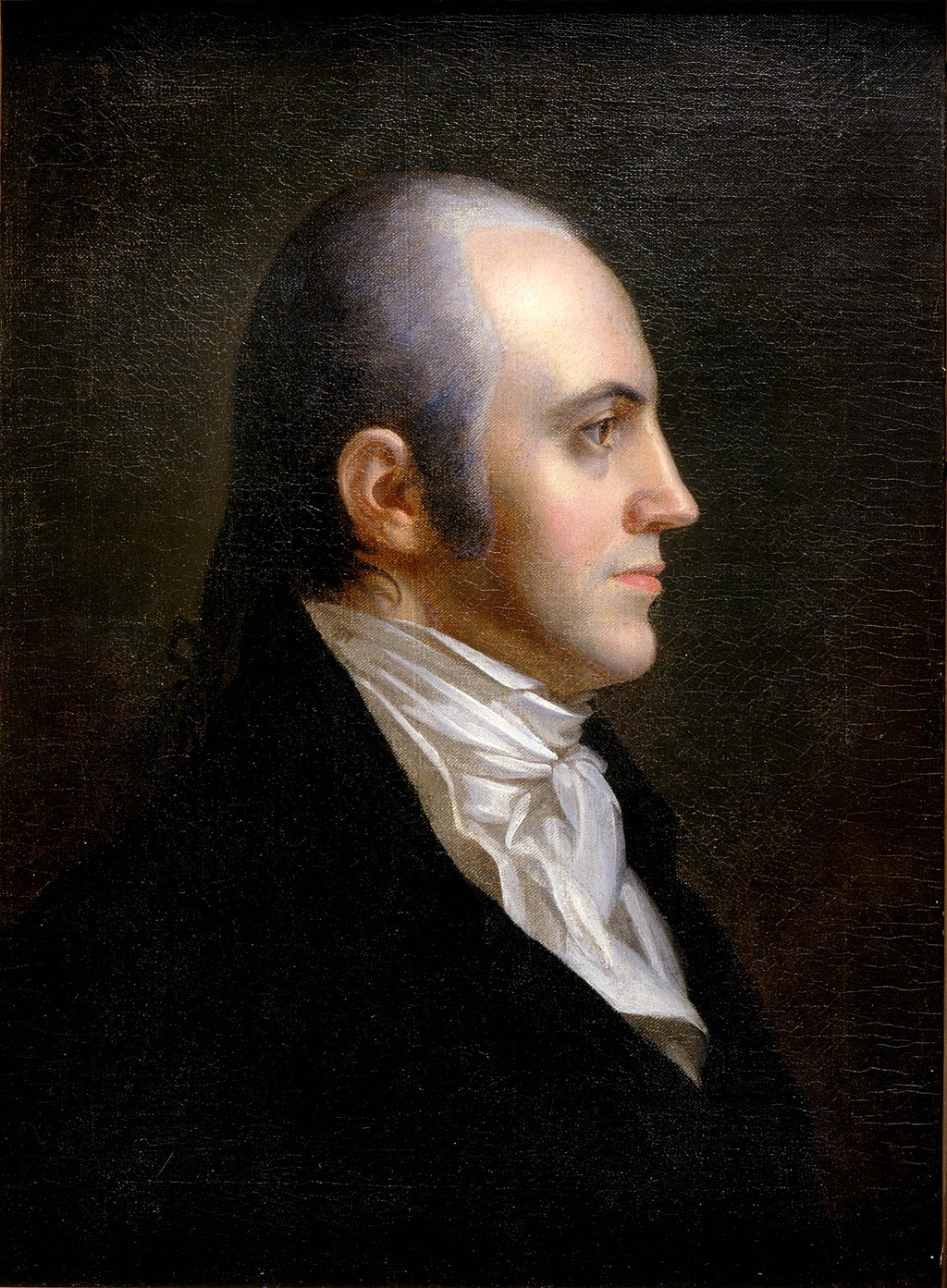

Captain Kidd in New York Harbor. By Jean Leon Gerome Ferris.

By a simple twist of fate that might more appropriately be called unbelievably bad luck, Captain William Kidd, my roguish ninth-great-grandfather, stands today as perhaps the most famous “pirate” of all time. A larger-than-life figure in his own lifetime and the original source of many of the enduring myths of cutlass-wielding sea robbers we now hold dear, the New York seafarer who helped build the original Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan has captivated the imaginations of children and adults alike for 325 years now. Indeed, without my salty ancestor there might never have been fictionalized swashbucklers of the likes of Long John Silver, Captain Hook, Captain Blood, or Captain Jack Sparrow, for Captain Kidd, more than any other sea rover during the Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730), has done the most to immortalize the association of treasure maps, buried chests of gold, silver, and jewels, and macabre ghost stories—with pirates.

For four centuries and counting, he has been an American cultural icon and the international brand name for Piracy, Inc., with countless books, short stories, articles, ballads, and songs written about him, as well as rock bands, pubs, restaurants, streets, and hotels named after him. Because of his villainous reputation and pivotal role in the creation of buried-treasure mythology, he was a favorite of such literary titans as Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Robert Louis Stevenson, as well as pirate artist Howard Pyle and prominent New Yorker and U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. Today, there are hundreds of websites on Captain Kidd, including more than a few with helpful tips on where plucky treasure hunters can find his long-lost fortune. In the U.S. alone, legend still places buried chests of Captain Kidd’s treasure in a multitude of locations not only in New York but Maryland, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Maine. Because of our enduring fascination with both the man and myth, he has secured his place in the pantheon of American folk heroes as our maritime Kit Carson and Jesse James.

However, while many people have heard of the swashbuckling “Captain Kidd the arch-Pyrate,” few know that he was not only a towering war hero as a lawful private naval commander, or privateer, in King William’s War between England and France (1689-1697), but one of early colonial New York’s most esteemed citizens, who hobnobbed with colonial governors and the merchant elite. But even less well known is that he was married to one of the city’s most dazzling socialites on Manhattan Island, Sarah Bradley Kidd, a larger-than-life figure in her own right. In fact, the romance between William and Sarah Kidd is one of the greatest New York love stories of all time.

ΨΨΨ

Born in 1654, William Kidd was an educated man who could read and write and trace his roots to a humble, upstanding, and loving Protestant Christian family hailing from Soham Parish, Cambridgeshire, England. However, he was also a restless and adventurous soul, who went away at an early age to sea as a cabin boy from the port town of Dundee, Scotland, and knew only the life of a mariner. Considering himself as much a Scotsman and colonial American as an Englishman despite his ultimate English lineage, he served as an English privateer against the Spanish, or “buccaneer” as they were called by the English in the West Indies, and occasional merchant seaman throughout the 1670s and 1680s. Trained in mathematics and navigation, he sailed extensively to and from the Caribbean, the American colonies, the metropole of London, and quite possibly the South Sea, which we know today as the Pacific Ocean.

Though free-spirited and bacchanalian, the buccaneers were licensed, government-sanctioned privateers not outlaw pirates plundering the ships of all nations indiscriminately. Privateering as a respectable seafaring profession for both patriotism and profit has existed at least as far back as the Roman Republic, and privateering ships and the privateersmen who manned them (both are referred to as “privateers”) served the function of an auxiliary, cost-free navy that were recruited, commissioned, and unleashed upon the enemy under government-issued letters of marque and reprisal when the resources of combatant European nations were overextended. During Kidd’s early career as a duly licensed Caribbean buccaneer, he plundered the Spanish on land and by sea along the coast of Central and South America and in the Gulf of Mexico and West Indies —not only to earn a decent living wage but to patriotically weaken Spain’s grip in the New World. But he was no outlaw pirate.

The buccaneers’ lifestyle was built upon a modern-like, egalitarian political framework. Their homegrown system of direct democracy resulted in a unique brotherhood defined by honor, trust, integrity, and lending a helping hand to those in need. It played a huge role in nurturing Kidd’s core democratic value system and well-known generosity. During his later seafaring career in the 1690s as a privateer commander, he employed African Americans, Native Americans, East Indians, and Jews as share-earning stakeholders aboard his ships-of-force, and he went out of his way to help seamen’s wives, parentless children, and his family relations and was heavily involved in community service.

By 1688, Kidd had made New York City his home and purchased several prime real-estate properties overlooking the pristine East River. He could afford properties that today are some of the most valuable real-estate holdings in the entire world because he had made a bundle of gold dust and silver coinage from his respectable privateering activities throughout the 1680s. As a private commerce raider taking richly laden enemy ships as prizes, he had earned far more than the average overworked and downtrodden Royal Navy or merchant deck hand, who typically netted a paltry £16 to £25 ($5,600 to $8,750 today) per annum.

In his own day, Kidd was described as a “hearty,” “lusty,” and “mighty” warrior of “unquestioned courage and conduct in sea affairs,” as well as a man of exceptional physical strength and skill in swordsmanship. Taking part in an occupation where violent hand-to-hand combat was the norm rather than the exception, the tall, robustly built, and pugnacious colonial English-American felt no qualms about killing a sworn enemy in close quarters with sharpened steel and snarling lead pistol shot. He was, in essence, a seventeenth-century U.S. Navy Seal.

History has not revealed to us the exact date or circumstances that the rough-and-tumble buccaneer William Kidd and the charming, comely, and very-much-married Sarah Bradley Cox first laid eyes upon one another—but circumstantial evidence points to the year 1688 as the likely starting point. In this historic year that marked the joint ascension of the Dutch Prince William of Orange and his English wife Princess Mary Stuart to the English throne in the Glorious Revolution, thereby securing a Protestant succession, Kidd was thirty-three years of age and had recently made New York his home port. Meanwhile, at this time, the woman who would soon be the love of his life was an eighteen-year-old English mistress, who had attained elevated social station through her marriage to an elderly, wealthy flour merchant and city alderman of Dutch descent named William Cox. By hook and by crook, William Kidd and the “lovely and accomplished” Sarah would find a way to be together as far more than just friends—while she was married to William Cox.

Historians have long been intrigued with Sarah Bradley, the woman who stood resolutely by Captain Kidd when he was fighting for his life as an accused pirate, and yet little is known about her. Born in England in 1670, she was brought to New York in 1684 at the tender age of fourteen by her father Captain Samuel Bradley Sr., along with her two younger brothers, Samuel, Jr. and Henry. Sarah’s family was by no means rich, but the recently widowed Captain Bradley was wealthy enough to pay for the passage for himself and his three children, and Sarah brought with her a substantial 114-ounce silverware collection, a sign of modest wealth and substance at the time.

To secure his daughter’s future and a position in New York polite society for the Bradley family, within a year of their arrival to the New World the captain partnered with the wealthy merchant William Cox and arranged a marriage between his daughter and the anglicized Dutchman. Sarah and Cox, a man two and a half times her age, were married on April 17, 1685, but he died a mere four years later, on August 1689, in a bizarre drowning accident off Staten Island. At the time of Cox’s death, Kidd was in the West Indies fighting the French in King William’s War as a privateer and making a name of himself as a combat hero. Within a year after Sarah had met Kidd in 1688, the two had begun a clandestine romantic relationship that resulted in a son born out of wedlock several months after Cox’s death. Due to the moral and religious constraints of the age, the future Mr. and Mrs. Captain Kidd gave their infant son William up for adoption to Kidd’s aunt Margaret Ann Kidd Wilson living in Calvert, Maryland.

Unfortunately for Sarah, following Cox’s drowning, his estate was swiftly tied up in bureaucratic red tape by Jacob Leisler, the acting lieutenant governor of New York province, and his political cronies at City Hall, who desperately needed money to finance William III’s expensive war against France. The German-born, militant Calvinist Protestant was a New York merchant, former militia officer, and the leader of Leisler’s Rebellion. After seizing power in June 1689 in the name of William and Mary and the Glorious Revolution, Leisler held office as acting lieutenant governor until March 1691, when Kidd returned to New York to play a pivotal role in his removal from power and to take Sarah as his lawfully wedded wife.

Due to her difficult circumstances and with Kidd away fighting the French in the Caribbean, Sarah briefly took a second husband, a Dutch merchant named John Oort, in 1690. Sarah and Oort were married less than a year when he died suddenly and unexpectedly on May 14, 1691, of unknown causes—and two days later she married Captain Kidd. As a two-time widow, Sarah would have been left alone again at age twenty and heavily in debt, but before Oort’s body had even gone cold she and Kidd tied the knot and thus began one of the New York’s greatest, most romantic, and swashbuckling marriages of all time.

ΨΨΨ

The wedding of Mr. and Mrs. Captain Kidd was celebrated on May 16, 1691, the same day that Jacob Leisler was hung and beheaded for treason. The ceremony took place inside the Dutch-built Fort William church at the southern tip of Manhattan Island near present-day Battery Park, where Anglican services were held at the time. Following his return to New York in early March, Captain Kidd’s star had risen quickly as a lawful privateer and community leader. He had swiftly secured a position in the inner circle of the city’s economic and political elite by playing a key role in taking down Leisler, who had proven to be a corrupt, incompetent, and despotic colonial administrator. In fact, the war hero Captain Kidd was so highly regarded as a member of New York polite society that the municipal clerk listed the sea captain’s occupation as “Gent” for gentleman instead of “mariner” on the marriage license. That must have brought a grin to the rough-and-tumble buccaneer who had pillaged and plundered all across the Caribbean and Spanish Main.

Although their affection for one another was the driving force behind their marriage, their love match proved to be beneficial to both parties and Kidd brought Sarah immediate financial security. Not only did he possess several valuable real-estate properties from his privateering cruises over the past two decades, he owned his own formidable 16-gun privateering and merchant ship, the Antigua, given to him by Christopher Codrington, the English governor of the Leeward Islands, as a reward for his bold military service on behalf of the Crown in the Caribbean. He had also been rewarded by New York’s royal governor, Richard Sloughter, and the governor’s council with a substantial amount of money for his privateering efforts in forcing Leisler’s surrender and for a libel case involving the merchant ship Pierre, which had been unlawfully condemned by Leisler in Vice-Admiralty court.

That summer, Captain Kidd headed out to sea once again with a commission signed by Governor Sloughter to battle French privateers sneaking down from Canada to wreak havoc in Long Island Sound and along the New England coast. When he returned to New York in August with an enemy warship as a prize along with her valuable cargo, his reunion with Sarah was a joyous one. Hundreds of New Yorkers turned out with her, her father Captain Bradley, and her brothers Samuel and Henry from the docks, rocky coastline, and oyster-shell-strewn beaches to greet the heroic seafaring commander guarding their coasts from French attack and capturing enemy prizes.

Soon after his return, Kidd made the transition from serving “His Majesty’s forces and good subjects” as a licensed privateer to full-time merchant sea captain. The former buccaneer, now closing in on his thirty-seventh birthday, agreed to “settle down” at the request of his wife, who wanted him to spend more time at home. In a chauvinistic age when a husband could legally beat his spouse with no consequences, Kidd was passionately in love with Sarah and not only listened to her but dutifully obeyed her. As a self-made gentleman hobnobbing with the wealthiest New Yorkers along with his young socialite wife, he now turned away from dangerous privateering missions and towards lucrative commerce on short, reasonably safe trading voyages to the English and Dutch West Indies he knew so well.

For the next five years, the Kidds lived the most placid and domestically fulfilling part of their lives. During this halcyon time, William and Sarah enjoyed the birth of their two daughters, Elizabeth in 1692 and little Sarah in 1694, and they were finally together much more than they were apart. It was during these years that they became Manhattan’s most dazzling married couple.

ΨΨΨ

Though William and Sarah had been born mere “commoners” in England, by the fall of 1694 they were not only living the American Dream but wining and dining with the Philipses, Nicolls, Van Cortlandts, Emotts, Bayards, Livingstons, Grahams, and others from Manhattan’s most well-respected families. Enjoying his ongoing success as a Caribbean trader and having recovered Sarah’s rightful inheritance with the settling of John Oort’s estate, the widely known, well-liked, and reputable Captain Kidd stood as one of the wealthiest citizens in the city, with his and Sarah’s individual net worth at last combined and under his control as head of household. As a New York man of affairs, he had even recently served as a jury foreman on a high-profile legal trial, and he and Sarah continued to be part of the “English” inner circle in the anglicizing city in the aftermath of Leisler’s Rebellion.

New York at this time was as progressive and cosmopolitan a metropole as existed in the New World, just as it is today. Although the original Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam remained predominantly Dutch in culture and had undergone significant anglicization since the English conquest of 1664, it was the most ethnically and religiously diverse English colony in North America. English language, churches, and settlers made up only a portion of a society that was more than half Protestant Dutch and included French Huguenots, Walloons (French-speaking Protestants from southern Netherlands), Scots, Irish, Swedes, Finns, Germans, Norwegians, Jews, and a large population of Africans, some of whom were free. The mixture of orthodox and moderate Calvinists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, dissident Baptists, and Lutherans to go along with a smattering of Dunkers, Quakers, Jews, Catholics, and African conjurors brought with it a religious freedom unmatched anywhere else in the American colonies. This ethnic and religious diversity encouraged a plethora of viewpoints and made New York America’s first grand experiment in multicultural democratic republicanism.

In the colonial era, the waterfront along the East River separating New York City from Long Island was Manhattan Island’s most coveted real estate and the political and merchant elite lived in the South Ward, Dock Ward, and East Ward. William and Sarah lived with their two daughters in a sprawling waterfront home at 119-121 Pearl Street in the multicultural, polyglot, and eclectic neighborhood of the East Ward. The Kidds’ combined properties included what are today some of the most expensive real estate holdings on the planet, worth hundreds of millions of dollars: 90-92 and 119-121 Pearl Street; 52-56 Water Street; 25, 27, and 29 Pine Street; and the Saw Kill farm in Niew Haarlem at today’s 73rd Street and the East River.

Their luxurious Dutch-style, brick mansion at 119-121 Pearl Street was not only located in one of the most desirable waterfront locations in the city but was one of the largest and finest homes in the entire province. Built two generations earlier by the wealthy Dutch merchant Govert Lockermans, the three-story house overlooking the East River had a high peaked gable roof, scrolled dormers, fluted chimneys, and was filled with handsome and abundant furnishings, including a Turkeywork carpet and chairs, four feather beds, an abundance of silver plate, and Sarah’s homemade English coat of arms. To top it all off, the entrepreneurial sea captain had a special rooftop crane to load and unload trade goods and supplies into a storage room on the third floor.

The Kidd family’s view of colonial New York City, the Great Dock, and Harbor must have been a stupendous sight to behold. Across the East River, in Brooklyn and the verdant green farmland of Long Island stretching beyond, they looked out onto more than a dozen Dutch windmills spinning in the ocean breezes. A stone’s throw from their front door, they listened to playfully barking seals and the soothing melody of seawater lapping gently against the pebble beach stretching north of the Great Dock. Looking toward the sky, they gazed up daily at immense flocks of seagulls and bluebills soaring above fisherman waist-deep in the water unloading nets filled with oysters.

In the afternoons when their daughters were napping, William and Sarah would take pleasant strolls along the East River, down oyster-shell-littered Pearl and Dock Streets, and also along Broad Way, Wall Street, and Beaver Street, past the affluent three-story houses of red, yellow, and brown Holland brick with fancy glass windows and high peaked gabled roofs. The couple would also take Elizabeth and little Sarah to the marketplace the original Dutch inhabitants called Het Markvelt. The commercial district a stone’s throw from their house was always bustling with people buying, selling, and unloading goods. To seaward, the Great Dock hummed with industry and the Kidds looked out every day at hardy White and Black men loading and unloading pipes of Madeira wine, stacks of animal skins, barrels of flour, piles of lumber, crates of munitions, kegs of gunpowder, and casks of dry goods amidst a forest of furled masts.

When the summer heat became oppressive, they would take their daughters up the East River to the cool shade of the family’s 19¼-acre Saw Kill farm located north of the city in New Harlem, where Sarah’s father lived. With their young girls in tow, they took pleasant strolls and picnicked on the spacious rural property amidst green pastures, freshwater ponds, and woodlands of majestic copper beech, oak, cherry, and birch in what is today northern Central Park.

At this time, in the sixth year of King William’s War, there was an explosion of piracy in the Indian Ocean, and New York overnight became the foremost pirate enclave in the New World. The Red Sea Men, as they were known, were some of the most audacious freebooters of all time, preying on the shipping of the Great Mughal of India, Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir I. The Great Mughal’s richly-laden ships sailed annually in late summer from Surat, India, to Mocha and Jeddah on the Arabian Peninsula, where the devout travelers rested before continuing to the holy city of Mecca by foot to pray and trade before Allah in the sacred pilgrimage known as the hajj. On both the outgoing and return voyage to India, the fleet was the richest prize in the East and a magnet for the Red Sea Men sailing out of primarily New York and Newport, Rhode Island, in the American colonies.

Although Captain Kidd would not even entertain the possibility of becoming a Red Sea Man and going a-pirating, it couldn’t have been easy for him to turn his back on so much wealth and temptation. Along with Sarah, he saw the signs of the astronomical riches reaped from the Indo-Atlantic “sweet trade” every day along the wharves, in the shops, taverns, and warehouses, and in the colonial mansions of his wealthy merchant friends and the governor himself. Most importantly, when he looked within his own elevated social circle, he must have wondered what his and Sarah’s life might be like if he did cross the line into piracy.

When he was in port, he and Sarah attended sumptuous parties hosted by Governor Benjamin Fletcher (1692-1698) and the Philipses, Bayards, Nicolls, van Cortlandts, DeLanceys, Emotts, Grahams, and other high-society movers and shakers. At these fashionable New York galas, the men typically dressed in silk waistcoats with jeweled buttons, full wigs, and lace cuffs, while the women wore the latest fashions from London: narrow-waisted, floor-length, bright-colored dresses of silk or satin, with a slight décolletage in the front and padded bustles, which plumped out the backside. They talked about the French and Indian attacks up north in King William’s War and how New Yorkers were secretly providing a safe haven for New Englanders accused of witchcraft; but what dominated the conversations were the stories of treasure chests full of gold, silver, and precious jewels and bales of rich silks pouring into the colonies from the Red Sea trade. In the Roaring 1690s, New York was one of the wealthiest colonies in the Atlantic world through a combination of legal shipping and the pillaging of the Mughal Empire. Plundering the rich Muslim heathens of the East was widely accepted by colonial Americans since it brought desperately needed gold and silver specie into the colonies, thereby helping overcome England’s draconian Navigation Acts that stifled American commerce and the lack of a New World banking system.

By the spring of 1695, Kidd’s ears had been filled for two years with tales of the fantastic riches there for the taking in the East Indies, relayed to him by both returning Red Sea Men and mega-merchants who traded with the pirates of Madagascar, like Frederick Philipse, with whom he and popular Sarah regularly socialized. Hearing these almost mythical stories, at some point he decided he wanted to be more than just a merchant captain making runs for sugar, spices, and rum to the West Indies and part-time privateer pestering the French in local waters.

There was just one catch: he absolutely refused to become an outlaw pirate. So, he made the decision to sail to London on a trading voyage and while there procure a privateer commission directly from the Crown. It was a combination of the feverish excitement generated by the Red Sea trade, his advancing age, his undying patriotism, and his lust for adventure that drove him to pursue his dream at this late stage of his maritime career. He loved Sarah and his daughters and was very happy in his marriage. He enjoyed his new house, his wealth, his wide circle of friends and colleagues, and his stature as a New York society gentleman. But he wanted to take one last shot at a grand adventure, perhaps to recapture the freedom and excitement of his buccaneering days in the Caribbean. More importantly, he wanted to be something more, to accomplish something grandiose and magnificent, and he wanted to do it in the service of king and country. Given the inherent dangers, Sarah tried to talk him out of the enterprise. Although Kidd was passionately in love with his wife, listened to her, and heeded her wise counsel, this time he overruled her.

With Sarah’s eventual blessing, he procured a letter of recommendation from his high-powered friend James Graham, attorney general of New York and protégé of Sir William Blathwayt, the secretary of war and a wheeler-dealer in imperial patronage in London. Graham laid out the case to Blathwayt for Kidd to be awarded a royal privateering commission based upon his extensive skill as a mariner, his bravery, and his devotion to duty as a patriot in King William’s War. “He is a gentleman that has done his Majesty signal service [and] has served long in the fleet & been in many engagements & of unquestioned courage & conduct in sea affairs,” wrote Graham. “He has been very prudent and successful in his conduct here and doubt not but his fame has reached your parts and whatever favor or countenance your Honor shows him I do assure your Honor he will be very grateful.”

In early June 1695, with his letter from Attorney General Graham in his pocket that he hoped would open doors to imperial sponsorship, Kidd bid a teary-eyed farewell to Sarah, their two daughters, and his father-in-law Captain Samuel Bradley Sr., and set off for London in the Antigua with a cargo full of goods to sell and to make a name for himself as a Crown privateer. It proved to be a huge mistake and he should have listened to his sensible and loving wife.

ΨΨΨ

Upon reaching London, Kidd was recruited by a group of wealthy Whig financial backers to carry out a dangerous privateering mission that would make King William III and themselves a bundle of money but was of questionable legality. Based on his sterling reputation, the investors issued him a government commission to fight the French and another to capture Red Sea pirates in the Indian Ocean and they constructed a 34-gun warship, the Adventure Galley, to his specifications. Kidd’s government sponsors included not only the king as a silent partner but Lord Bellomont, a powerful Whig House of Commons member and soon-to-be royal governor of New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire; Lord John Somers, Lord Chancellor and Keeper of the Great Seal; Charles Talbot, the Duke of Shrewsbury, Secretary of State; Admiral Edward Russell, First Lord of the Admiralty and Treasurer of the Royal Navy; and Henry Sidney, the Earl of Romney, Master General of Ordnance. Some of the most powerful men in all of England, the five lords of London who served as his business partners were members of the Whig Junto that administered the English government, and they had all been early and steadfast supporters of William and Mary in the royal couple’s 1688 ascent to the English throne in the Glorious Revolution.

Kidd initially said no to the command of the risky venture. But Lord Bellomont threatened to have him arrested, to seize the Antiguafrom him so he could not sail back to New York, and to have his seamen press-ganged away from him by the Royal Navy if he didn’t agree to command the voyage. Not only that, but Bellomont warned that he would “oppress” him in New York when he took office as governor of the province. Kidd backed down. Confidant in his abilities and knowing firsthand from the streets of New York the untold riches awaiting him in the East, he decided to carry out the difficult mission rather than make enemies of Bellomont and the other unspeakably powerful English noblemen, who offered him further assurances “of their support and his impunity from criminal prosecution.”

Kidd’s reluctance to command the expedition was well-founded, for his 1696-1699 voyage to the Indian Ocean turned out to be an epic disaster and turned him overnight into one of the most notorious criminals of all time. By the fall of 1697, a year into the expedition, he and his crew had still not encountered a single enemy French or pirate ship that could be seized as a legitimate prize and they had suffered one disaster after another, including raging storms, a tropical disease outbreak, severe thirst and starvation, and repeated attacks by the East India Company, Portuguese, and Moors (Muslim East Indians). Increasingly desperate to earn some money under their standard “no prey, no pay” privateering contract, a large number of his New York and New England seamen wanted to become full-fledged pirates themselves and plunder the ships of all nations to garner a big score. However, the law-abiding Captain Kidd would not allow any violations of his two legal Crown commissions.

While quelling a mutiny, Kidd accidentally killed his unruly gunner, William Moore, a man with two prison sentences to his name, by smacking him in the head with a wooden bucket. Though he felt badly about the incident, many of his men never forgave him and the simmering discontent aboard the Adventure Galley grew. Following the mutiny, Kidd seized two Moorish ships, the Rouparelleand Quedagh Merchant, that presented authentic French passports and together provided a valuable haul of gold, silver, silks, opium, and other riches of the East. However, while these wartime seizures were 100% legal and he himself never once committed piracy in India, he soon thereafter looked the other way during the capture of a Portuguese merchant galliot that presented official papers of a nation friendly to England (at least marginally).

His seamen sailing separately from his 34-gun galley in the captured Rouparelle seized from the Portuguese vessel two small chests of opium, four small bales of silk, 60 to 70 bags of rice, and some butter, wax, and iron. It was a paltry haul, and if Kidd hadn’t later become such an infamous figure, few would have cared that he had turned a blind eye to his unruly sailors from a separate ship plundering a few foodstuffs from a Catholic merchant vessel crewed by Moors. However, it was technically piracy even though Kidd wasn’t directly involved in the capture. He only allowed the seizure to placate his mutinous crew, which had by this time divided into “pirate” and “non-pirate” factions aboard his three separate privateering ships; and in reprisal for the damage inflicted upon the Adventure Galley and serious injuries sustained by a dozen of his crewmen from two Portuguese men-of-war that had attacked him without provocation months earlier.

The reason that Captain Kidd became such a notorious figure overnight was because of the anti-piracy propaganda campaign of the English Crown and East India Company. Because England had failed to arrest and capture the most dastardly and successful pirate, the Englishman Henry Every, following his 1696 rampage of the Great Mughal’s treasure fleet, the authorities made the colonial American privateer Kidd out to be a Public Enemy #1, even though King William III and his greedy Whig leaders in England had commissioned him as their personal pirate-hunter to earn gargantuan profits for themselves. Because Kidd followed in the wake of Henry Every and the fiercely territorial East India Company considered him an “interloper” in their waters, the English authorities created Treasure Island-like yarns of a roguish, treacherous, and mean-spirited Kidd who never existed because they were unable to capture the real pirate Every and needed a scapegoat.

Despite the numerous challenges he faced during his perilous voyage and a full-scale mutiny because he refused to go all-in on piracy, Kidd miraculously made it back to the American colonies from Madagascar with around £40,000 ($14,000,000 today) of treasure in his hold and the French passports that proved he had taken the Rouparelle and Quedagh Merchant legally in accordance with his commission. However, when he and his small band of loyalists who hadn’t mutinied reached Antigua on April 2, 1699, they received heartbreaking news. The Crown, at the urging of the East India Company, had sent an alarm to the colonies in late November 1698 declaring them pirates and ordering an all-out manhunt to capture and bring them to justice. Kidd decided to try to present his case for his innocence and obtain a pardon from his lead sponsor in the voyage, Lord Bellomont, who had by this time had taken office as the royal governor of New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

But his first priority before sailing to Boston was to make arrangements with his lawyer, James Emott, to reunite with his beloved wife Sarah and their two young daughters in Long Island Sound.

ΨΨΨ

On June 25, 1699, Sarah took in the sight of her husband standing at the railing of his recently acquired ship, the St. Antonio, anchored off the eastern end of craggy Block Island, Rhode Island. He looked strikingly dashing in his waistcoat with nine diamond buttons and chestnut-colored wig parted in the middle and hanging to his shoulders. A moment later, she and her daughters were helped aboard the sloop by Captain Kidd and his seamen. Reunited for the first time in two years and nine months, Sarah gave her husband a welcome-home embrace befitting a man who had risked everything to return home to her and their daughters and clear his good name. The girls joined them in the hugging as the crew hauled up the belongings. Kidd squeezed Elizabeth and little Sarah tight and gave them presents of sugar candy. For the next several hours, the deck of the St. Antonio was the scene of fiddle music and a bountiful feast of roasted lamb and pig, fresh oysters, cabbage, salt, sweetbreads, and much hard cider.

Six days later, Captain Kidd and his reunited family sailed into the Puritan stronghold of Boston, the husband-and-wife team deciding to roll the dice with Bellomont, who by this time had promised his business partner an official pardon in writing. Though much of Kidd’s lawfully captured silver and gold, jewels, and bale goods remained with him aboard the St. Antonio, he had safeguarded a significant portion of his booty with his good friend Captain Thomas “Whisking” Clark, a New York political leader and church vestryman who had picked up Sarah, Elizabeth, and little Sarah and sailed them to Block Island; his old Rhode Island privateer friend, the war hero Captain Thomas Paine; and John Gardiner, the proprietor of Gardiner’s Island in Long Island Sound. He had told Sarah about these critical reserves before they sailed for Boston in case things went badly with Bellomont, whom they both did not fully trust.

It is these unusual precautions that have contributed mightily to the longstanding myth of Captain-Kidd-the-Treasure-Chest-Burying-Scoundrel—with treasure hunters still flocking today to the U.S. East Coast, Caribbean, Madagascar, and even the South China Sea in search of Captain Kidd’s long-lost treasure. The irony is that in 1699 these treasure-burying antics that “would forever affect popular culture’s view of piracy” were performed solely because the captain and his astute wife didn’t trust Kidd’s principal business partner, Lord Bellomont, the titled English earl who had strong-armed him into commanding the fateful voyage and promised to have his back.

They were right not to trust Bellomont, for five days after arriving to Boston and undergoing three separate interrogations by the royal governor, Kidd and his loyal crew members were arrested and thrown in the Boston City Jail. The Crown authorities swiftly seized all of his gold, silver, bale goods, and other assets as well as coins, silverware, and personal items belonging to Sarah and her housekeeper. Sarah was crestfallen, for she now had nothing to live on in unfamiliar Boston or to bail her husband out of jail. She pleaded with Bellomont not to take her and her housekeeper’s rightful possessions that had nothing to do with the captain, but the gouty English earl considered all three of them criminals in their own right. His primary objective was to keep Kidd under wraps and get his hands on all of the money and goods without colonial officials asking too many questions. He hoped to simultaneously secure the treasure for himself and his fellow Whig lords to alleviate his heavy debts and to protect himself and his fellow investors from the newly ascendant Tories, who had targeted the Whig Junto over the Kidd affair, which at this point was the top news story of the day.

For the next eight months, Captain Kidd was incarcerated with heavy 16-pound iron shackles around his ankles in solitary confinement in atrocious Stone Prison. Throughout the fall and winter, Sarah remained in Boston with her daughters, fighting for her and her husband’s rights under the law. With the help of her Boston lawyer and the deputy postmaster, she prepared legal petitions requesting prison conjugal visitation rights, the return of her husband’s clothing seized by Bellomont, and the restoration of her and her housemaid’s belongings illegally taken by the governor. However, Bellomont refused every single one of her petitions and Sarah only obtained visitation rights by appealing to the charity of the sympathetic jailkeeper, without the governor knowing.

With no income to feed herself, her daughters, or housekeeper or to help her husband locked up in Stone Prison, and with Bellomont having reneged on his promise of protection, she had no alternative but to turn to sketchy characters to retrieve her husband’s stashed-away gold. But before the New York she-merchant, socialite, and now fallen woman could take charge of her family situation, she was arrested and thrown in the dank Boston City Jail by order of Bellomont. In seizing her, the English earl had truly sunk to a new low, for he had no reason to toss her into the slammer except to intimidate her. However, she was able to dictate a note from her jail cell for delivery to Kidd’s friend Captain Paine, asking for “twenty-four ounces” of the gold her husband had left with him and instructing him to keep the rest in his custody until she, or her husband, called upon him again. The gold was soon retrieved from Paine, the privateer hero of Rhode Island, by a veteran sea dog named Captain Andrew Knott. Now Sarah had money again for lawyer fees, bribes, and meals for her husband, who for nearly three weeks now had been subsisting on mostly bread and water.

During Kidd’s incarceration in Boston, the husband-and-wife team hatched various escape plots during Sarah’s sporadic conjugal visits under Bellomont’s nose. During one such visit on February 5, 1700, talking in whispers so as not to be overheard by the jailers, they put together a bold jailbreak plan. Two days earlier, the fourth-rate warship HMS Advice, captained by Robert Wynn, dropped anchor in Boston Harbor. The ship destined to convey Captain Kidd to London for trial had completed the Atlantic crossing in five short weeks and, after refitting, would be ready to load him up for the return journey back to England, along with more than thirty other “pirate” prisoners and £14,000 worth of treasure ($4,900,000 today) recovered by Bellomont. When Sarah learned of the arrival of Wynn and the Advice, she went immediately to visit her husband in Stone Prison. She knew their time was running out and they had to make their move.

The critical first part of the escape plan called for Sarah to sweet talk or bribe the jailor to remove Kidd’s irons that had been chaffing his ankles for the past six months. Kidd contributed to the scheme by complaining about the pain in his legs from the heavy irons. It is not certain what combination of pleading, bribery, or sweet talking was utilized, but on Wednesday, February 8, the jailer took off Kidd’s iron shackles to alleviate his discomfort.

Now the escape plan entered a second phase. Sarah’s job was to find a way to enable Kidd to physically sneak out of his solitary confinement cell. The two most promising alternatives were filing through the heavy iron bars or picking the lock, so that he could slip out undetected late at night. There was no time to spare with the HMS Advice having arrived.

They made plans to escape on February 13, five days in the future. This would give Sarah time to make all the arrangements for the jailbreak. At this point, the best option seemed to be smuggling in tools so that he could saw through the iron bars. The captured Red Sea pirate James Gilliam, who had sailed from St. Mary’s to America as a deckhand with Kidd after the pirate-faction had mutinied, had used an iron crowbar and metal files during his attempted escape back in December; however, he had made too much noise and was caught before cutting through the final iron bar at his cell window. Sarah’s second option was to persuade the jailer, whom she knew was a considerate man since he had let her husband out of his irons, to set Kidd free for a price.

Unfortunately for the husband-and-wife team, Bellomont sent an official to check on Captain Kidd at this time and when the gouty earl learned that his fallen protégé was unshackled and moving about his cell, he became irate. He soon thereafter sent the high sheriff and armed deputies to Stone Prison to forcibly collect Kidd and load him onto the Advice. By the time Sarah awoke at the seaside inn she was staying at with Elizabeth and little Sarah, her husband had been dragged out of his solitary confinement cell and shackled aboard the Royal Navy prison ship. It pained her that he had spent nearly eight months in Boston’s two toxic lockups without being charged with a single crime, but she was crestfallen when she learned that he would now be shipped off for a probable show trial and grisly hanging in London without the opportunity to bid a proper farewell to her and their daughters.

Upon learning that her husband was held captive aboard the Advice, Sarah tried to visit him so she could say goodbye. But Bellomont would not allow any visitors. Saddened but undaunted, she sought out Captain Wynn, hoping that he might be more sympathetic. She was able to introduce herself one frigid afternoon shortly before the ship’s departure, just as he was leaving the governor’s mansion.

She expressed her disappointment and distress to the Royal Navy commander that Bellomont was not allowing her to visit her husband aboard the HMS Advice, and especially that she and her daughters were being deprived the right to bid him a proper farewell. She then made a polite request. Despite Bellomont’s ban, could Wynn find it in himself to grant her and her daughters just five minutes to say goodbye to their husband and father, and to send him off with their affection and a letter to remember them by? He was innocent, she pointed out, and he deserved the right to say farewell to his family, who he might never have the chance to see again.

Since the arrival of the Advice to Boston Harbor, she and her husband had decided that it would be best if she, Elizabeth, and little Sarah return to New York and remain in America if he was put aboard the prison ship to be sent to London for trial. Not only did he want to ensure their safety, he couldn’t bear the thought of his wife and daughters seeing him disgraced in irons in atrocious Marshalsea or Newgate Prison, or to see him on trial for his life before a courtroom of hostile English judges and prosecutors eager for his execution and salivating at the prospect of his gruesome public hanging.

Though Captain Wynn appears to have been a reasonable man, his fear of provoking Bellomont’s rage was too great for him to fulfill her modest request. He regretfully informed her that he had been ordered by the royal governor to hold Captain Kidd as a “close prisoner” with no visitors or letters; and that he could not violate his military orders by allowing her to visit or deliver a message to her husband, despite the fact he was under heavy guard.

Unwilling to allow it to end there when her husband’s life was on the line, Sarah reached into a leather pouch, pulled out a golden ring, and pressed it into the Royal Navy officer’s hand. Wynn maintained that he could not accept gifts and attempted to return the ring to her.

But Sarah refused to take it back and pleaded with the captain to keep it. All she asked in return was that Wynn be kind to her husband during their extended sea voyage to London. However, he once more objected, stating that he was unable to accept any presents from prisoners or their loved ones.

Feeling powerful emotions sweeping through her, she took a step forward and gazed directly into the eyes of the Royal Navy officer. “Captain, I must insist you keep the ring as a token until we meet again,” she said, struggling to hold back the tears. “On the day you bring my husband back to me.”

And with that Sarah Kidd walked away and into the pages of history. Not yet thirty years old, she had stood resolutely by her man for the past nine months, sailing with him and their daughters aboard the St. Antonio and living like Hester Prynne in a repressive Puritan citadel that was utterly alien to her. Like her husband Captain Kidd, she had been abandoned by everyone once she became tainted and expendable, including her Boston lawyer who went over to Lord Bellomont, and she had even done a stint in the atrocious City Jail. Yet never once during the interminably long, bitterly cold, and desperately lonely winter did she waver in her support of her beloved husband, or in her belief in his innocence.

A day or two later, on March 10, 1700, the HMS Advice set sail from Boston Harbor for London and the trial of the century, while Sarah returned with Elizabeth and little Sarah to her home in New York. All she and her young daughters could do now was pray.

ΨΨΨ

On May 23, 1701, Captain William Kidd was hung at the gallows at Execution Dock in Wapping, East London. The New York privateer had been tried two weeks earlier at the Old Bailey on five counts of piracy and one count of premeditated murder. Although the piracy charges against Kidd were weak and the death of Kidd’s gunner William Moore had been an accident while quelling a mutiny, it didn’t matter. The courtroom drama proved to be nothing but a sham trial to make an example of Kidd to protect England’s trade with Great Mughal and the East India Company’s profitable monopoly. He had been swiftly convicted on all counts based on the perjured testimony of his heavy-drinking surgeon, Dr. Robert Bradinham, and deserter-seaman Joseph Palmer, both of whom served as the Crown’s star witnesses and received full pardons for their betrayal of their captain.

In the Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730), large numbers of Londoners flocked to public pirate executions, but the turnout for Captain Kidd’s public execution was unprecedented due to his notoriety and the frenetic newspaper coverage. To witness death up close, scores of pleasure boats anchored close to the north shore next to the gallows, and a huge crowd of more than 10,000 souls packed the narrow streets, Wapping Stairs, and the wide foreshore. The colonial American sea captain—who only a short time earlier had been heralded as the “trusty and well-beloved Captain Kidd” by King William III himself—died just as a blood-red sun set over London Town and the gently rippled waters of the Thames. Four days after he stopped twitching and three tides had washed over him, his soggy corpse was coated with tar and hoisted in a gibbeted iron cage downriver at Tilbury Point, where it would remain for the next twenty years to serve as the English State’s grisly warning to other would-be pirates of the fate that awaited them if they dared disrupt England’s valuable trade relations with India by pursuing the short but merry life of a plundering freebooter.

At the gallows at Wapping, Captain Kidd’s last spoken words were for his wife Sarah and their daughters:

[Captain Kidd] expressed abundance of sorrow for leaving his wife and children without having the opportunity of taking leave of them, they being inhabitants in New York. So that the thoughts of his wife’s sorrow at the sad tidings of his shameful death was more occasion of grief to him than that of his own sad misfortunes.

On August 4, 1701, nine weeks after his gruesome public hanging, Sarah received a knock at the front door of her house on Pearl Street, and a New York official notified her that her husband had been executed in London on May 23. Since Captain Kidd had been “attainted as a pirate,” the official presented her with a signed warrant for the confiscation of her husband’s estate. Under English law, she owned nothing as the widow of a pirate and was cast out onto the street, along with Elizabeth, little Sarah, and housekeeper Dorothy Lee. She promptly waged a fierce legal battle against the Crown, arguing that the properties and household possessions were acquired from her first and second husbands and from Captain Kidd prior to his alleged piratical acts. The case would drag on through the courts until 1704 when Queen Anne finally granted back to Sarah the title to her properties and possessions.

Since Kidd had sailed from Boston in irons in March 1700, she had struggled to put her life back together while living quietly in the city with Elizabeth and little Sarah, but times were hard as many of her New York friends ostracized her. Her only consolation was that Trinity Church honored the Kidd family’s ownership of Pew Number 4, allowing her and her daughters to regularly attend church services in return for her husband’s generosity to the community back in 1696. To assist with the Anglican house of worship’s construction, Kidd had, prior to departing on his voyage to the Indian Ocean, lent his runner and tackle from the Adventure Galley as a pulley system to help the workers hoist the stones. The Kidd family pew was right up front near the rector and bore the inscription “Captain Kidd—Commanded ‘Adventure Galley.’” Unfortunately, Captain Kidd never had the opportunity to pray with his family at the church he helped build in the New World. As one of New York City’s greatest links to its historic past, the latest incarnation of legendary Trinity Church stands today in the exact same spot where Captain Kidd lent his runner and tackle over 330 years ago.

Sarah eventually remarried and died a moderately wealthy widow on September 12, 1744. By this time, she had moved back to New York from New Jersey and was living in her old home on Pearl Street where she had lived her best years with Captain Kidd. Fittingly, she is buried today in the churchyard of Trinity Church on Wall Street in Manhattan.

Although today we know Captain Kidd as one of the most notorious scoundrels of all time, my ninth-great-grandfather was no more of an “arch-Pyrate” than Horatio Nelson or Jean Paul Jones—both of whom are recognized today as national seafaring treasures.Thus, the great irony of the legendary Captain Kidd is that, as historian Philip Gosse declared over a century ago, he was “no pirate at all.” He was, in fact, a progressive New York gentleman, colonial American coastguardsman and war hero, and beloved husband and father who helped build up America’s greatest city and a democratic New World. Together, he and his fiercely devoted and courageous wife Sarah enjoyed one of New York’s most adventurous and unique romantic partnerships of all time during the Golden Age of Piracy.

The ninth-great-grandson of legendary privateer Captain William Kidd, Samuel Marquis, M.S., P.G., is a professional hydrogeologist, expert witness, and bestselling, award-winning author of 12 American non-fiction-history, historical-fiction, and suspense books, covering primarily the period from colonial America through WWII. His American history and historical fiction books, have been #1 Denver Post bestsellers and received multiple national book awards in both fiction and non-fiction categories (Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews Book of the Year, American Book Fest and USA Best Book, Readers’ Favorite, Beverly Hills, Independent Publisher, and Colorado Book Awards). His in-depth historical titles include Blackbeard: The Birth of America and have garnered glowing reviews from colonial American history and maritime historians, bestselling authors, U.S. military veterans, Kirkus Reviews, and Foreword Reviews (5 Stars).