Mayer Amschel Rothschild, the founder of the Rothschild banking dynasty famously said “Give me control of a nation’s money and I care not who makes its laws”, suggesting that whoever controls the economy of a country has more power than the lawmakers. The Swadeshi Movement, while fundamentally political, was India’s realization of this truth and understanding the importance of economic control. Over the years, many historians and scholars have given their definition of the term “Swadeshi”, all revolving around self-sufficiency and local self-reliance.

Shelton Rozario explains.

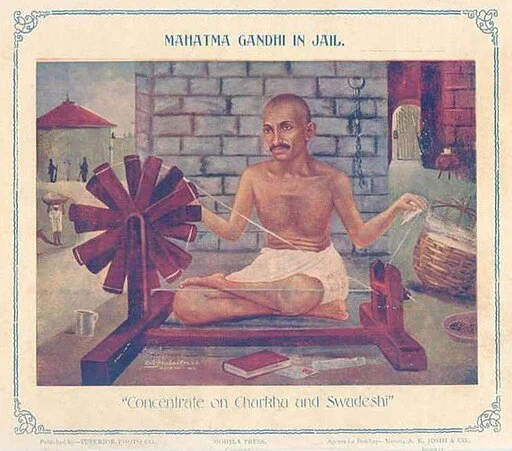

"Concentrate on Charkha and Swadeshi," a poster in the Swadeshi Movement. It shows Mahatma Gandhi using a Charkha.

According to Gandhi, the term Swadeshi is “that spirit within us which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote.” He promoted the importance of indigenous skills, using them to live a simple and dignified life. For Sri Aurobindo, “It is an intellectual change, it is a spiritual change, it is a political change…Swadeshi is that which belongs to our own country. When applied to industry and commerce it means the preference for our own articles produced by Indian labour and the exclusion of articles produced by the labour of foreign people.” Lisa N. Trivedi opines that the “social collective of Bharat (the dominant indigenous term for India) was the template on which popular swadeshi repertoires were forged.”

The Swadeshi Movement went beyond mere boycott and eventually became a way of living. This idea has been stressed upon in Gandhian philosophy and also in influential works like that of Rabindranath Tagore’s 1904 essay ‘Swadeshi Samaj’. It emerged as a mass political movement from 1905 onwards and developed into a crucial instrument for economic policy making post 1947, after Indian independence. This movement is about the making of a local economy and revival of the industries that were disbanded by the British. Despite harsh measures such as arrests and lathi charges to suppress it, the movement had already succeeded in forging a sense of national identity among Indians.

Drain of Wealth and Early Swadeshi Awakening

The economic awakening in colonial India occurred after the ‘Drain of Wealth’ debate put forward by Dadabhai Naoroji. In his work ‘Poverty and Un-British Rule in India’ originally published in 1901, he spoke about how Britain was practically bleeding India’s revenue. Dr. Dhananjaya in her study of this writes how “The Indian government was also forced to impose significant home charges as reparations on the people of England due to the political, administrative, and commercial ties between the two countries. The Home Charge covered annuities for irrigation and railroad projects, interest on public loans obtained from England, and payments to British workers in India in the form of salaries and pensions.”

Naoroji and the Indian National Congress had put forward their demands for industrial development, reduced taxes and promotion of Indian industries which were never given any importance. Between 1883 and 1892, Naoroji said that the total drain amounted to Rs. 24 crores which substantially increased to 51.5 crores by 1905. D.E. Wacha, the President of the Indian National Congress in 1901 also suggested that the drain was about thirty to forty crores. The figure varies as per the calculations of historians but drain of wealth from India was undeniably a major issue. In 1891, the Swadeshi agenda was adopted by the Indian National Congress. This became a national cause after the British Government amended the 1894 cotton duties in 1896 to benefit the textile manufacturers in Manchester by imposing a uniform 3.5% duty on manufactured Indian cloth.

Nitin Pai while tracing the early economic developments during the Swadeshi Movement highlights how “swadeshi…already became a social proxy against what many saw as political “mendicancy”. Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1896 organized boycotts and publicly burned foreign cloth in Bombay. Mahadev Govind Ranade's work through the Industrial Conference of Western India aimed to promote industrial development in Bombay in the late 1880s. This phase marked the establishment of early Swadeshi stores, indigenous banks and the rise of an entrepreneurial Indian class. Nitin Pai sheds light on the global movements during this emergent political phase such as the abolition of slavery in America, the American Civil War, Industrial Revolution, all culminating in changing the “pattern of the deployment of Indian capital.”

Swadeshi and Local Enterprises in Full Swing

When Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal on October 16, 1905, his reasons revolved around Bengal being too large of a province. However, the main reason as supported by many historians was to curb Bengali nationalism, using the old tactic of “divide and rule” from the British playbook. In a 1903 memo, Curzon wrote: Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided will pull in different ways. East Bengal and Assam with approximately 31 million people became one unit while Bihar, Orissa and West Bengal formed the others. Little did Curzon expect that this move would act like a catalyst for the already brewing Swadeshi Movement.

Hundreds and thousands of people gathered on August 7, 1905 at Calcutta’ Town Hall chaired by moderate leader Surendranath Banerjee. Following this, students opted out of government schools, local banks and mills sprouted to promote the local economy. Some of the most prominent Swadeshi enterprises from Bengal include Acharya P.C. Ray's Bengal Chemicals, Bange Lakshmi Cotton Mills, Calcutta Potteries and the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company (1906) by V.O. Chidambaram Pillai. In her article ‘Boycott of Lancashire Cloth: The real economic battle’, Diksha Tyagi observes how Import of foreign cloth declined by 1.5 crore rupees in 1907…Bombay’s textile mills, benefiting from increased demand for indigenous cloth, earned profits of over 2.7 crore rupees…” She further says that even Brahmins boycotted foreign goods and refused to perform pujas with those items.

When Gandhi arrived in 1915, he gave the movement a broader meaning by incorporating social, religious and cultural aspects. He promoted the khadi (cloth woven on handloom from fibers like cotton, silk, wool, etc.) as an alternative to the mill cloth and began spinning it in his Sabarmati Ashram. After World War I and brutal effects of the Great Depression in America, the British economy was slowly but surely crumbling. Khadi became a symbol of economic sufficiency and by 1925, the All India Spinners’ Association (AISA) was set up. They offered employment to women too who now became active economic contributors.

From Khadi to National Consciousness

Another major blow to the British economy was the Dandi March of 1930, a part of the larger Civil Disobedience Movement. Following the principles of satyagraha (truth) and ahimsa (non-violence), this was a salt march against a series of British laws that prohibited Indians from locally producing or selling salt. The Swadeshi movement post 1930s went beyond producing cloth and aimed at creating a decentralized economy. This was the opposite of what the British believed in : a centralized model of production. Nitin Pai writes “As India headed towards independence, swadeshi began to move from being an instrument of protest to a principle of economic policy of the new republic.”

The majority of the population of India during the 1940s had still not adapted to an urban lifestyle. In this sense, Gandhi’s vision of a self-sufficient village economy represents a microcosm of India itself. Trisha Rani Deka opines that Gandhi’s “entire effort of swadeshi was revolving around the village economy…village self-sufficiency, village self-government, cultivation of village and cottage industries were the main agenda in his concept of swadeshi.” Thus, this led to the revival of indigenous products, particularly handlooms and cottage industries. Gandhi himself said that his model was : “Not mass production, but production by the masses.” This community spirit further cultivated a collective identity and national consciousness which was rooted in atmashakti or self-reliance.

Interestingly for Gandhi, the total boycott of foreign goods or western items was never on the table. He would be willing to “buy surgical instruments from England, pins and pencils from Austria and watches from Switzerland” but “will not buy an inch of the finest cotton fabric from England or Japan or any other part of the world because it has injured and increasingly injures the millions of the inhabitants of India.”(Young India, 12-3-1925, p. 88). He was against mass industrialization as it would force villagers to leave their homes and craft, reducing them to factory workers. Even though the post 1947 models reflect a Nehruvian planning and state led heavy industrialization, Gandhi's Gram Swaraj ideals are reflected in the rural schemes and support for village industries.

Conclusion

India under a colony of the British was not only treated as a market and source of raw materials. For centuries under the rule of the British Raj, the Indian subcontinent was only a dumping ground for foreign grounds whose artisanal industries were dismantled. The Swadeshi Movement changed that and emerged as the first great reversal. What once was a dependent and culturally dependent colony saw an awakening and revival of its own local enterprises. As described by Gandhi : When every individual is an integral part of the community…when the economy is local… when homemade handicrafts are given preference, it is the real swadeshi.”

From the early efforts of the Indian National Congress to the growth of local enterprises and the entrepreneurial spirit, Swadeshi became a way of living. The pharmaceutical industries, banks, national schools and handloom industries laid the foundation of some big names that exist to this day. In many ways Swadeshi was India’s first “Atmanirbhar Bharat” that boosted the local economy via a model that revived its economy and embraced ethical consumption.

Over the past two years, Shelton has worked with various organizations as a content writer and contributes as a fact-checker for DigitEYE India, an IFCN signatory. He is passionate about history, politics and culture.

References

● Joseph, S. K. (n.d.). Understanding Gandhi’s vision of Swadeshi. Retrieved on October 19, 2025 fromhttps://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/understanding-gandhis-vision-of-swadeshi.php

● Aurobindo, Sri. “Swadeshi and Boycott.” Bande Mataram, 1907. Web. https://sri-aurobindo.co.in/workings/sa/37_06_07/0306_e.htm.

● Trivedi, L. N. (2003). Visually Mapping the “Nation”: Swadeshi Politics in Nationalist India, 1920-1930. The Journal of Asian Studies, 62(1), 11–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096134

● Dhananjaya. (2021). The Drain Theory of Wealth and Dadabhai Naoroji: An Overview. International Journal of Novel Research and Development, 6(7). https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2107007.pdf

● Pai, N. (2021, July 2). A Brief Economic History of Swadeshi. Indian Public Policy Review, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.55763/ippr.2021.02.04.002

● Tyagi, D. (2025, August 8). Boycott of Lancashire Cloth: The real economic battle. Organiser.https://www.organiser.org/2025/08/08/306782/bharat/boycott-of-lancashire-cloth-the-real-economic-battle/

● Deka, T. R. (2020). Gandhi’s vision of Swadeshi and its relevance. International Journal of Management (IJM), 11(10), 2587-2593.https://iaeme.com/MasterAdmin/Journal_uploads/IJM/VOLUME_11_ISSUE_10/IJM_11_10_260.pdf