This three-part series takes on one of America's most important founding fathers, John Adams. John Adams’ contributions to the founding, development, and success of the United States was unrivaled by others of his generation. In this series, I will examine John Adams’ life and contributions to the United States from three perspectives. First, John Adams the patriot. Second, John Adams the diplomat. Third, John Adams the Statesman.

Avery Scott starts part 1 below.

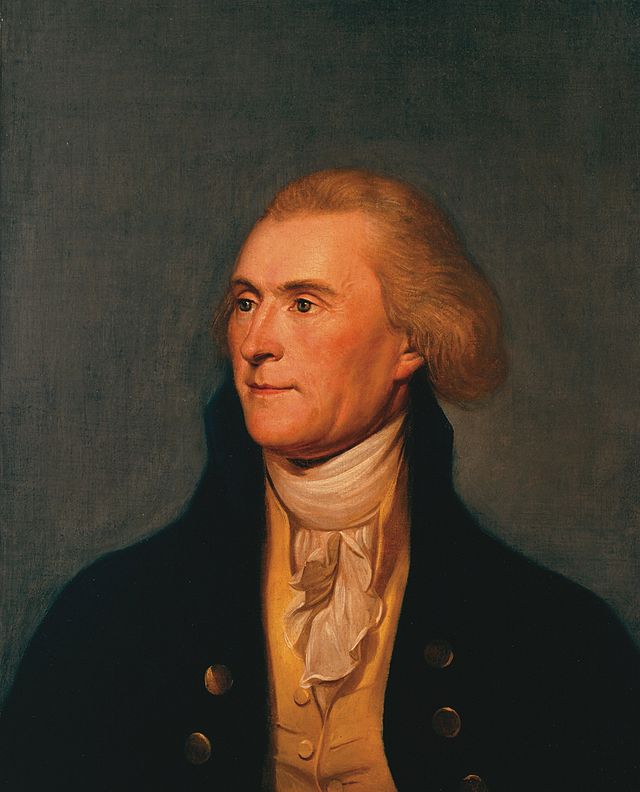

A 1766 portrait of John Adams. By Benjamin Blyth.

Introduction

John Adams' ascension to power was anything but smooth. He, unlike peers George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, was not born into riches. Rather, he was born to a working-class family in October of 1735. Adams was born in Braintree, Massachusetts to John Adams Sr. (Deacon John), a farmer and shoemaker, and Susanna Boylston. From an early age, Adams was a dreamer. He dreamt of being successful and prominent. Despite his dreams, Adams' weaknesses often hindered his ability to obtain his desired success. Frequently he complained of, “dreaming away the time” and wasting too much of his day on the frivolous. Fortunately for Adams, he was born in a time perfect for dreamers. Witnessing the French and Indian War, the effects of slavery, his time serving as a schoolmaster, and the oratorical and legal examples of men such as James Putnam played a major role in shaping the future president. Additionally, Adams' time at Harvard College enriched him, and provided him the liberal education that would become so necessary during his variety of roles in support of the United States. After Adams time at Harvard, he was struck with the decision of a career. Adams settled on the law, completing his legal education, and beginning his career in 1758. For some time he struggled, but eventually became a successful lawyer with a reputation for honesty, integrity, and hardwork. It is around this time in which Adams courts and marries Abigail Smith in 1764. This union would eventually produce six children - one being a future president himself. Unfortunately, the Adams family was not destined to enjoy a lavish lifestyle that would have likely occurred in other circumstances. Rather, at British Parliament's passing of the Sugar Act, Currency Act, Quartering Act, and the Stamp Act, they turned the reluctant to rebel Adams - into a Patriot.

The Patriot

After the passing of the Stamp Act, Adams began writing large political pieces in support of American rights. His first such writing titled, A Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law, was one of his most successful. However, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, allowing for relative calm in the colonies for the next few years. Despite the temporary calm, it was not long before Adams was thrust into the biggest moment of his personal and legal career - the Boston Massacre.

Legal Career

One year before the Boston Massacre, in April of 1769, Adams defended Michael Corbett, a sailor aboard the Pitt Packet, after he killed Lt. Henry Paton of the British Vessel Rose. After he attempted to press Corbett and three other men into British service, Corbett lobbed a harpoon at Paton, killing him. Troops from the Rose took the sailor into custody, who was tried in Boston on murder charges. John Adams expertly defended his client, just as he would during the Boston Massacre in 1770. Thus displaying his expert legal mind, and his affinity for the rights of man.

On March 5th, 1770, a British guard was being taunted by a throng of Colonists, unhappy with his presence. Eventually, a small squadron of troops, and their captain Thomas Preston, appeared as reinforcements. The unfortunate event ended with the British troops firing into the crowd of protestors, killing five. As if the incident were not stressful enough on the young Adams, he was soon asked to provide legal defense for the British troops. Despite his concerns, Adams agreed to provide the services at no charge. Adams spared all of the troops any prison time, and only minor punishments for two soldiers. While it may seem odd that this fervent patriot would defend those he despited, it displays the principles that the rebels were fighting for in action. They felt that freemen have rights that must be honored, and not least of these is the right to legal counsel and fair trials. Patriotism, in the eyes of John Adams, did not mean that he would disgrace those he disagreed with. Rather, he would work tirelessly to ensure that their rights were also upheld.

Beginnings of Revolution

In December of 1773, the Boston Tea party was orchestrated by the Sons of Liberty in retaliation for the taxes charged on tea, and the crown sanctioned monopoly by the East India Company. In the act, 342 chests of tea were destroyed and dumped into Boston Harbor - infuriating the crown. Adams was ecstatic to hear about the act and what it meant for America, but knew that at that moment that war would be imminent. As retribution, the crown closed the port of Boston in 1774 as a part of the Intolerable Acts, until the tea was paid for.

In the same year as the intolerable acts, Adams was elected to the First Continental Congress. The first Continental Congress was not nearly as exciting as the Second Continental Congress. However, there were important measures taken that showed the colonists' willingness to submit to British rule under the condition that they were given their due rights. Also, the congress approved such measures as a non-importation and a non-exportation agreements in an attempt to hurt the British economy. Eventually the First Congress adjourned in October of 1774, and shortly after in 1775 the Second Continental Congress was held.

The Second Congress

The Second Congress saw some of the biggest contributors to the revolutionary cause come together, to make some of the biggest decisions America has ever seen. First and foremost, Adams nominated George Washington to serve as Commander of the Continental forces. A decision that, despite Adams later comments about Washington, was one of the biggest of both their careers. A strong presence was needed to support the Colonies in their attempt to defend against British rule, and Washington fit the mold. Also, Washington was a Virginian, which was important due to Virgina being the largest and wealthiest of all the colonies. Congress felt that the leader of the United Colonies should hail from that state. Additionally, The second Congress also voted to outfit privateers, disarm Tories, and build frigates for a new Navy. Each of these was of major importance, and played a key role in the development of the war. Finally, a committee of five, made up of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman, were appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence from Britain. After some planning and discussion, Jefferson was tasked by the committee as a whole to write the majority of the document with only input and minor changes from the others. After completion of the document, much debate ensued regarding the act of independence. During the debate Adams displayed his true patriotic valor, defending the document and pushing for independence from Britain. There were many members of congress that were not yet ready to commit to independence, but Adams' resilience, passion, and hard work convinced many of the delegates that independence was necessary. And on July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted to approve the Declaration of Independence.

Once independence was agreed upon, some painful revisions to the Declaration were necessarily undertaken by Congress, at times decimating the document that Jefferson worked so diligently on. One of the biggest sections removed, and one that Adams felt the strongest about, was the chastizement of the King for bringing slavery into the Colonies. This section was removed at the urging of other members of Congress, because slaves and the slave trade were directly associated with the livelihoods and economic status of many members. It is in this debate, that we see the Patriot Adams stand to defend, not only white colonists, but also African Americans. Adams hated the thought of slavery, and never personally owned a slave. He felt strongly that people fighting for freedom should not be holding others in bondage. Unfortunately, Adams lost this debate and on July 4, 1776, the official wording and document was approved for publication. But it was not until August 2, 1776 that the document would be officially signed. Once independence was declared, a host of other issues became necessary to address. Questions of laws, governance, finance, arming of troops, and administrative duties had to be attended to. Just as Adams was a fervent patriot in fighting for independence, he fought the same for these issues.

What do you think of John Adams as a patriot? Let us know below.

Sources

John Adams by David McCullough

The Indispensables: The Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware by Patrick K. O'Donnell

Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow