Battered by wind gusts, the Avro Lancaster bucked and lurched as its crew struggled to keep the plane aligned with the signal fires set by the French Resistance fighters two thousand feet below. The “Lanc,” one of the Royal Air Force’s (RAF) workhorse bombers, was a homely beast. It had four noisy propellers, a protruding snout, and a pair of ungainly tail fins. Built to drop bombs four miles above Dusseldorf and Dresden, the Lanc was ill-suited for the stealthy parachute operation it was being asked to perform in the predawn hours over Occupied France.

Here, Timothy Gay continues the story of Stewart Alsop. Part 1 is available here.

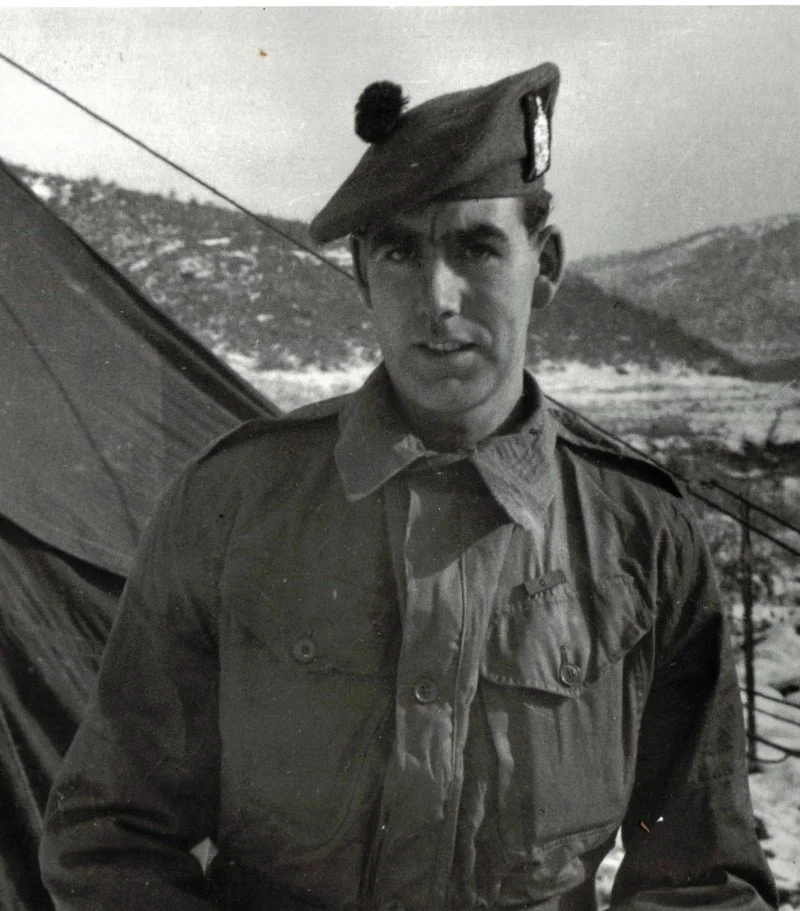

The instant Lt. Stewart Alsop leapt from the Lancaster, Sgt. Dick Franklin realized that Team ALEXANDER’s leader had messed up. Franklin was so rattled by his commander’s gaffe, he confessed in his memoirs a half-century later, “that I didn’t know whether to shit or go blind.”

With the RAF’s rookie jump master screeching “No!” Franklin grabbed French Lt. Richard Thouville and kept him from following Alsop through the hole. As the radio operator, Franklin knew that the Jedburgh mission could ill afford to have all three principals dumped willy-nilly atop the French countryside.

The Lanc continued to drone southward. Within a few minutes the crew had feathered its engines, which dropped its altitude by a thousand feet or more. Soon enough, the jump master was flashing a red light and hollering “Go!”

One at a time, Thouville, Franklin, and the SAS troopers all plunged through the hole. The inexperienced Canadian airmen had done a yeoman job maneuvering the Lanc close to the Maquis’ L-shaped groundfires – or so they thought at the time.

Franklin, a golf enthusiast, landed some 150 yards left of the fires, “about like my normal bad hook,” he kidded years later.

He alighted smoothly enough but stumbled after impact; fortunately, his helmet stayed put as his chest banged against the ground. Unhurt, he popped up, and began retrieving his chute. He heard shouts, dropped the chute strings, and reached for his rifle, but was relieved to see friendly French citizens waving as they ran toward him. They were members of the Resistance reception committee.

Leave your chute – we’ll take care of it later, they told Franklin. They escorted him up a slight hill toward the groundfires. As they crested the ridge, a nervous Maquisard apparently mistook Franklin’s helmet for a German coal scuttle and opened fire. Fortunately, he was a lousy shot; no one was hurt and his Sten was quickly silenced.

Trying to get his bearings, Franklin began asking questions about their location and strategic situation. To his chagrin, he sensed that Team ALEXANDER had parachuted onto the wrong Resistance stronghold.

He learned that they were in the Haute-Vienne Department, some 70-kilometers northeast of their intended target – the BERGAMOTTE Resistance cell operating close to Limoges in the Creuse Department. In truth, there were so many Maquis groups going full-tilt in southern and central France in mid-August 1944 that it was tough for an air crew to figure out which set of bonfires was the correct one!

The Maquisards assured Franklin they would look for Thouville and Alsop. They motioned toward a peculiar-looking sedan and told Franklin he would be driven to their farmhouse headquarters. Just as they were climbing in, Thouville emerged from the other side of the bonfires, “full of piss and vinegar,” Franklin recalled.

Thouville’s chute had gotten snarled in some high-tension wires. He avoided electrocution but was frustrated that it took so long to cut himself loose. It also angered him that despite his best efforts, his chute stayed wrapped around the wires – a beacon for enemy patrols, he knew from his training.

Franklin, meanwhile, was fuming about the condition of his wireless set, which had gotten banged up upon landing. To make matters worse, Alsop, their commander, was nowhere to be found.

Thouville and Franklin were bemused by the bizarre-looking car driven up by the Maquis. Like many Resistance vehicles in the summer of ’44, it was a Gazogene, an ingenious contraption that ran on fuel generated by burning charcoal in a makeshift “oven” mounted on its front or back fender.

Gazogenes were smelly and temperamental, Franklin recalled, and tended to break down at the “most inopportune times.” But the charcoal miracles were helping to make the Maquis a far more mobile and lethal fighting force than was understood by Allied intelligence in London. The SOE-OSS brass was still under the mistaken impression that the Resistance operated almost strictly on foot.

They squeezed into the car, and with “headlights blazing,” rumbled down a dirt road toward the cell’s redoubt. Thouville and Franklin were amazed that the Maquisards were so brazen. Many were sporting bleu, blanc, et rouge armbands and not even pretending to be stealthy. On top of the Sten gun erupting, there had been a lot of noisy excitement around the groundfires. The clunky Gazogene, moreover, was making a racket as it lumbered toward the farmhouse.

Clearly, the Germans had lost control of the remote areas of the Haute-VIenne, if they ever had it – another fact not appreciated by Allied intelligence in August of ’44.

Thouville and Franklin’s first order of business was to meet up with the Maquis leadership and get a rundown on logistics and enemy strength; their second was to find Alsop – if, that is, he was findable. Their best guess was that Alsop had bailed out some 10 to 15 kilometers north of their position.

When Thouville and Franklin arrived, an impromptu party with Resistance fighters of both sexes was going full-bore at the farmhouse. The two Jeds were greeted with hugs, wet kisses on both cheeks, and copious amounts of wine. To Franklin, basically a teetotaler at that point, it tasted like vinegar.

Once the leaders began their briefing, it soon became evident that Franklin’s fear was correct: ALEXANDER had indeed been dropped in the wrong spot. The local Maquis leaders had requested from London gasoline, medical supplies, and a medic to patch up their wounded – not a team of commandos.

The Resistance guys were desperate, especially, for gas to run the cars and trucks they needed to conduct surveillance and hit-and-run raids. For months, they had subsisted on gasoline stolen from German supply depots. But once the enemy’s gas supplies began to wane, so did the Maquis’. With decent amounts of gas parachuted in from Britain, the guerillas could inflict even more damage, they told the Jeds.

If Thouville and Franklin were going to inflict optimal damage on the Wehrmacht, they would need to locate their team leader – and fast. With Allied invasion forces from the Riviera landings soon pushing the enemy northward, some 30,000 additional German troops would come crashing into south-central France, many of them looking for an escape route eastward through the Belfort Gap, the flat terrain between the Vosges and Jura Mountains.

Thouville that early morning organized a search party consisting of three Gazogene trucks-worth of Maquisards; he directed Franklin to stay at the farmhouse and tend to the radio. The three lorries with the strange ovens on their fenders lurched northward.

*

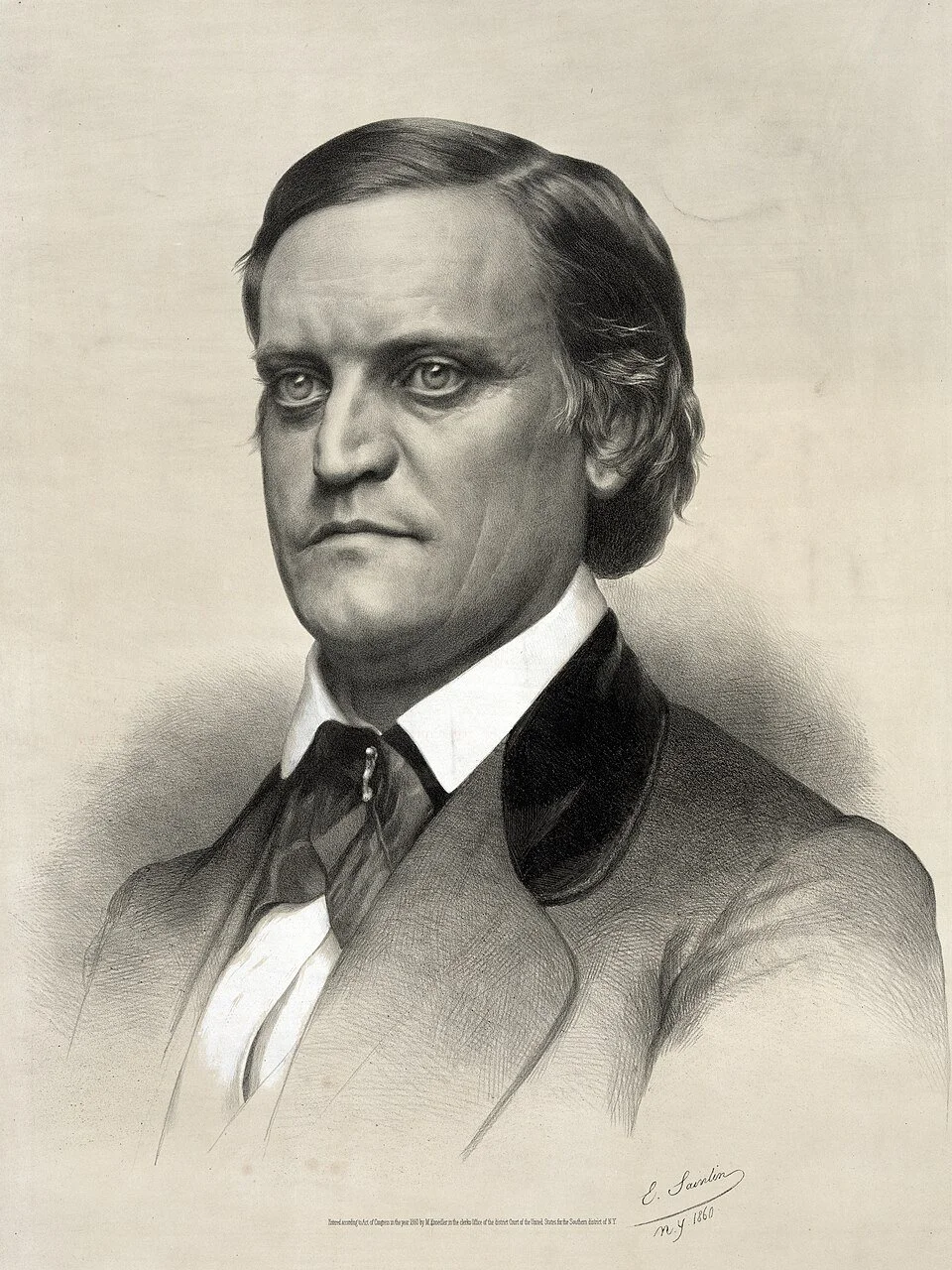

Unlike his Jedburgh comrades Alsop and Franklin, Lt. Renè de la Touche, aka Richard Thouville, was a military professional through and through. A graduate of St. Cyr, the French West Point, he was tall and slender; his demeanor, like his posture, was ramrod straight. His large ears and elongated nose protruded out from under his British Army cap. While fighting with the Free French in North Africa in ’42 and ‘43, he had been awarded the Croix de Guerre avec Palme.

At first, Franklin and Alsop found Thouville aloof. Eventually, though, the Frenchman loosened up, betraying a wicked sense of humor. But Alsop chose him as his Jed partner because he saw him as imperturbable; his discipline, Alsop thought, would prove vital on the ground in France. Plus, Alsop understood that Thouville’s mastery of French idiom and culture, especially his grasp of the internecine politics between Gaullist and Communist Resistance cells, would be a big asset.

He was given a pseudonym by Allied officials to protect his wife and children in case he was captured. The Gestapo was notorious for carrying our reprisals against the families of French soldiers who dared to continue the fight despite France’s surrender in June 1940.

*

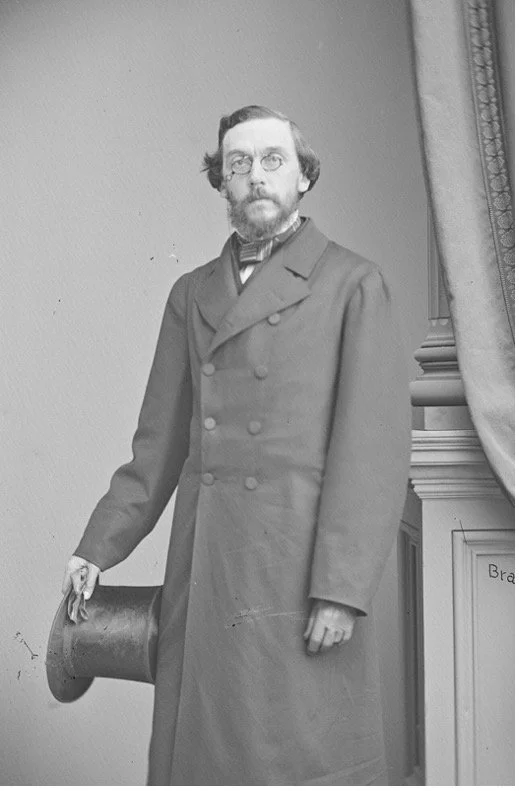

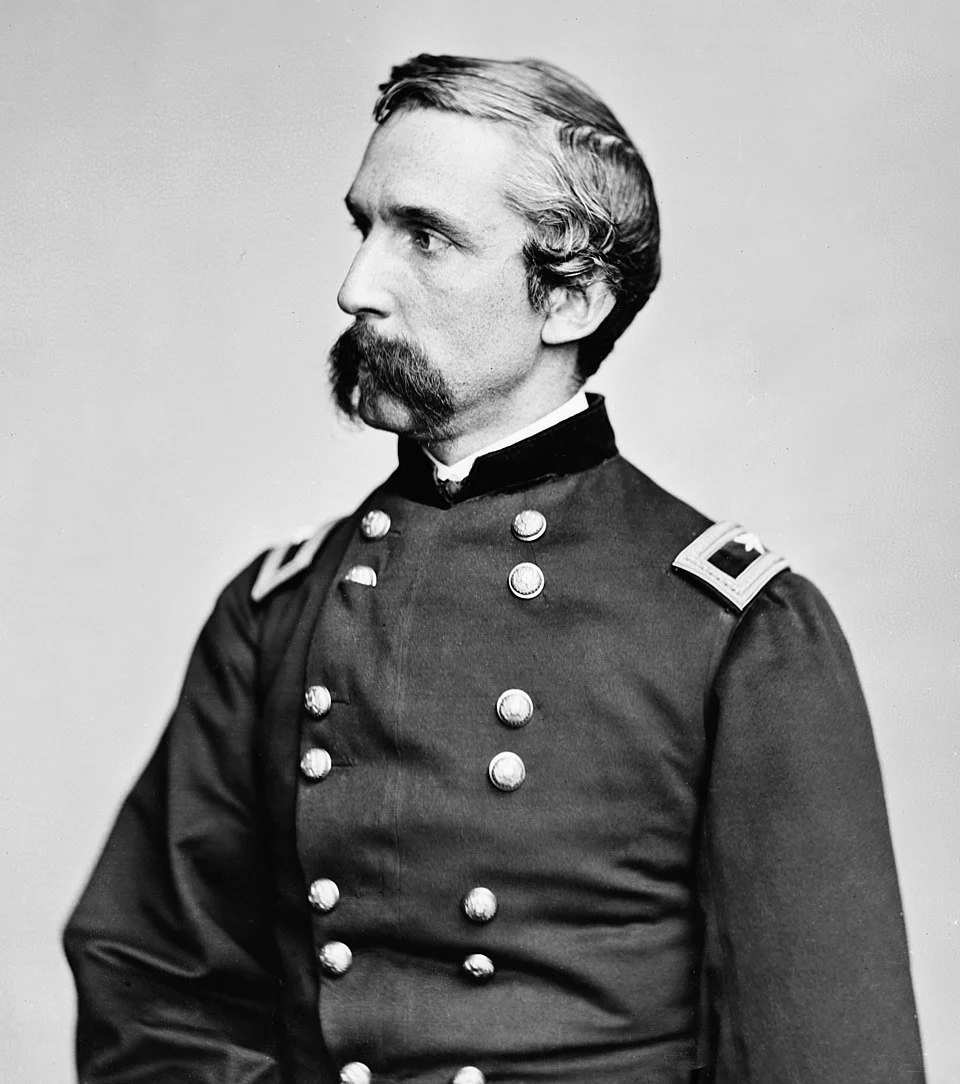

Norman “Dick” Franklin’s middle-class New Jersey upbringing was far removed from Stewart Alsop’s New England Brahmin background. Franklin was sharp-witted and adept with his hands, which is how he qualified for radio technician.

The bespectacled Franklin also had retained enough high school French to respond “oui” when asked if he was competent in the language. Unbeknownst to Franklin, at that moment he was being quizzed about his credentials to serve in the OSS’s super-secret Jedburgh program, then just getting underway. Franklin was a quick learner – a “whiz” at Morse code, Alsop recalled.

Courtesy of the OSS, Franklin mastered his commando skills at a variety of stateside training sites, among them the converted fairways of Congressional Country Club outside Washington, D.C., and a camp tucked astride western Maryland’s Catoctin Mountain near Shangri-La, FDR’s presidential retreat. Today, it’s called Camp David.

Like so many WWII servicemen, Franklin got married before being shipped out for combat duty. In his unpublished book, he wrote amusingly of the opportunities he had in France to enjoy the carnal freedoms triggered by La Liberación – but claims to have resisted the temptation.

*

By now, dawn wasn’t far off. Thouville and his Gazogene men drove north, combing back roads for Alsop while calling out, “Stewww-aaarrrt!!” According to Franklin’s account, they had no luck.

Worried that Alsop had been nabbed or shot, in Franklin’s recollection Thouville returned to the farmhouse, where a bash the ALEXANDER team later described as “lucullan” was still going strong. Wine and huzzahs continued to flow freely; Franklin remembered one “incomprehensible” toast after another being made to the United States of America and the imminent defeat of the Boche.

The Resistance leaders told Franklin and Thouville that they’d send another Gazogene crew out to search for Alsop while the Jeds rested. By now, the sun was peeking over the horizon, putting their leader into even deeper jeopardy.

Alsop had spent the bulk of the early morning skulking from bush to bush in what he thought was the direction the plane had continued flying, hoping to recognize a landmark or bump into a friendly farmer. As dawn approached, he found a road and concealed himself in some ferns, planning to hail a passerby if one happened along.

A while later, Alsop watched from his hiding spot as a truck slowed down. In Alsop’s memory, he faintly heard his first name being called out by someone with a French accent. He remembered thinking that it was one of two scenarios: either the Gestapo was ruthlessly efficient and had already learned the name of the Jedburgh team leader who was invading its turf – or that Thouville had somehow contacted the local Resistance and that these people were trying to rescue him.

Fortunately for Alsop, it was the latter. In Alsop’s recollection, Thouville was with the Resistance posse that early morning and helped pull him out of the woods. Franklin’s memory was that Thouville was still at the farmhouse. Either way, Alsop was surprised to see that his rescuers were wearing armbands. And he recalled being stupefied by the peculiar-looking vehicle they were driving. Once ensconced in the truck, he was delighted to learn that he was being taken to a rendezvous with his team and that a hearty meal would be served. He was famished.

While Alsop was being retrieved, one of the women at the farmhouse presented Franklin with a gift – a patch of his parachute. She was planning to use the rest of Franklin’s chute to sew clothes for Resistance families and to make U.S. and French flags, to be brandished as they routed the Germans.

Even though the sun was now up, Alsop arrived at the hideaway to plenty of “sourish wine,” as he later put it, and drunken revelry.

“Alors,” Thouville needled him, nodding toward some comely female Maquisards. “Tu aimes la France?”

“Oui,” Alsop smirked back. “J’aime la France beaucoup.”

Franklin pulled Alsop aside and gave his boss the bad news about the radio. Not only was the transmitter badly dented, but its output tube had been damaged. The radioman wasn’t sure it could be fixed.

For all three Jeds, the lasting impression of those first few days in Occupied France was the way the Maquis operated with impunity. The Jeds had been briefed at Milton Hall that the Germans had control over most of the major towns in southwest-central France but their grip on smaller villages and the countryside had begun to wane but was still formidable.

The truth was that Team ALEXANDER’s new friends could move from village to forest hideout without having to be furtive. It was only when they crossed theRoute Nationaleor ventured through one of the larger crossroad towns that they had to exercise caution. It took Allied intelligence weeks before they understood that, in most places, theMaquis’vehicles could travel at night with headlights on – and that additional supplies of gasoline would go a long way toward expelling the Germans from the heart of France.

After a few hours of sleep, the three ALEXANDER men borrowed bicycles to ride out to a high spot where they could test Franklin’s radio. When they got to the hilltop, Franklin, mortified, realized he’d forgotten his crystals. Without uttering a word, Lt. Alsop jumped on his bike and returned to the farmhouse. Alsop found the crystals and pedaled back to join his mates. Franklin expected “a good chewing out,” but Alsop never mentioned the incident, then or later.

To their surprise, the radio worked, at least for the moment. They got through to London HQ, but no message was sent in response.

They returned to the farmhouse, where they sat down with a British medical officer whose mission and identity were codenamed HAMLET. He had been secreted behind enemy lines for months. With HAMLET pointing out enemy strongholds, Team ALEXANDER mapped out ways to work their way to the Creuse Department, the home of their targeted Resistance partners, the BERGAMOTTE cell.

The trio also met up with colleagues in Jedburgh Team LEE that day, two Frenchmen and an American commander named Charles E. Brown III. LEE had been parachuted in the previous week and was using the farmhouse as its base of operation. With HAMLET, a full complement of Maquisards, various SAS operatives, and not one but two Jedburgh teams suddenly en résidence, a remote farm in Haute-Vienne had the feel of a Hilton hotel.

The ALEXANDER men didn’t stay long. HAMLET introduced them to another British medical officer, known simply as “The Major,” who had also been hidden for months in south-central France. If Thouville was the epitome of a Frenchman, Franklin observed years later, then The Major was the embodiment of an upper crust Brit.

“[The Major] had the sort of face,” Alsop wrote decades later, “that only England could produce: Blue eyes, a thin nose, droopy blond moustache, and a ready chin, the whole ensemble expressing the sort of assured lassitude which can be nothing but English. To top it off, he wore a monocle.”

The Major and his monocle craved action. “Just ‘doctoring’ must have been a little too unexciting for him,” Franklin noted.

Perhaps too nonchalantly, The Major volunteered to serve as their guide, explaining that he had a Resistance “acquaintance” situated between Haute-Vienne and Limoges who could help steer ALEXANDER’s vehicle through dicey territory. To Franklin, it sounded like The Major was saying, in a quintessentially British way, “’Ought to be a bit of sport, what?’ sort of a thing.”

A flatbed Gazogene truck appeared out of nowhere. Alsop and his men watched, impressed, as the Maquis guys placed protective sandbags around the perimeter of the truck bed and mounted a Bren machine gun on the roof of the cab and another on its tail. Several of the SAS commandos had been wounded; they were placed on stretchers behind the sandbags.

Well after dark, they bade farewell to their farmhouse friends and set off in the truck. The Major drove, with Alsop and Thouville also jammed into the cab. Franklin joined the wounded men in lying flat in the back, concealed by the sandbags. Just in case, everyone kept their weapons at the ready, pointed in every direction.

A little way into the trek they approached a sizeable village. The Major admitted he wasn’t sure which route to take. He took the chance, Franklin remembered, of knocking on the door of a large house. An angry voice yelled from an upstairs window that he was the mayor of the town and “What the blankety-blank hell did we want in the middle of the blankety-blank night?!”

Once The Major explained the situation, the mayor pointed to the correct street and urged them to be quick: there were a lot of Sales Boches (“Dirty Germans”) in the middle of town.

The Major climbed back into the cab and gunned it. Just as they cleared the town square, heavy gunfire erupted. Nasty red tracers flashed across their tail, but Alsop ordered the crew not to return fire. After some anxious moments, they breathed easier when the Germans chose not to pursue them.

Every now and then they had to stop to reheat the oven with charcoal. But their headlights stayed on as they drove through miles of forestland. Whenever they approached a junction, The Major stopped to send a scout forward to ensure that there weren’t any Sales Boches hidden around the next bend.

The Major’s intelligence source and his knowledge of the area’s backroads proved useful. They traveled all night; just before daybreak, they found the BERGAMOTTE camp hidden on the outskirts of Bourganeuf. The Maquisards were bivouacked beneath a series of repurposed Allied silk parachute tents” that stretched from tree to tree.

Once they sat down with the BERGAMOTTE leadership, it was clear that the big bosses in London had been right and wrong: Right that the cell had been under repeated enemy assaults, but wrong that they’d been compromised by the Gestapo. A festive party commenced, with surprisingly good food and enough red wine to cause Franklin to repair to the woods.

The next day Alsop sent Franklin off on a reconnaissance mission to the Route Nationale in the company of several Maquisards. They were under strict orders not to fire their weapons for fear they’d betray BERGAMOTTE’s forest hideout. At one point the recon party squirreled themselves into some ferns along the roadway as one German convoy after another motored past.

When Franklin returned to camp and reported his close calls, the Jed commander realized that he’s asked Franklin to take an unacceptable risk. A Jedburgh radioman was too valuable to send on such precarious missions. Alsop never again asked Franklin to go on risky recon.

That night, under the parachute canopy, the ALEXANDER guys and everyone else were awakened by a burst of gunfire. They scrambled for their weapons, fearing that the camp was being overrun by enemy troops. But it turned out that a young Maquis sentry had fallen asleep on guard duty; he accidentally dropped his chin onto the trigger of a Sten gun. Nobody got hurt

Alsop worried that if they attempted to engage Franklin’s radio around the camp, it might tip off the Germans’ direction-finding radio trucks, which had for four years roamed Occupied Europe, ready to pounce on any Resistance cell tapping the airwaves. Each night around midnight, the team would wander toward high ground to send their messages to London. Despite repeated contacts, there were still no specific instructions from their superiors.

The team quickly sensed that BERGAMOTTE was in decent shape and didn’t need their special services. The Creuse Resistance leaders urged them to help the Maquis contingent in the Dordogne Department, some 80 kilometers to the southwest. BERGAMOTTE’s intelligence suggested that the Dordogne Resistance was camping near the village of Thieviers and supposedly having trouble getting untracked.

To get to Thieviers, Team ALEXANDER would again have to traverse part of the Haute-Vienne. At that point, they’d been underground in France for little more than a week but had already crept through practically every region of the department.

They were assigned a guide who pulled up in a beat-up Citroën that ran on alcohol – not gasoline or charcoal. Audaciously flying from its hood were French and American flags.

Off they chugged to find the Dordogne sect of the FFI, the Forces Francaise de L’Interieure. The FFI, a term that encompasses most of the French Resistance forces in WWII, fought with such reckless ferocity that Allied soldiers nicknamed them “Foolish French Idiots.”

Their guide knew all the remote roads through the woods and could pinpoint enemy camps; given all the Germans around, he had no choice but to meander down one dirt path after another in the creek-swollen Plateau de Millevaches.

Alsop watched, amazed, as the guide inched the Citroën up to safe houses and camouflaged hideaways to get the latest intelligence on the location of the Germans and their Milicien cohorts. The guide smartly avoided all the potential ambush sites as they zigged and zagged. At the end of day two, the ALEXANDER men arrived at a ramshackle chateau about halfway on their roundabout route to Thieviers; they were told that they could use the property as their temporary base.

At the estate, Alsop and company shared quarters for a day with a Communist Maquis outfit that was part of the FTP, the Franc Tireurs Partisan. Jeds heading to France had been briefed about the erratic behavior of certain left-wing Resistance cells. Many Communist guerillas flatly refused to cooperate with the FFI or take instructions from Allied intelligence. Others fought but couldn’t always be trusted.

When the FTP guerillas at the chateau insisted on providing a round-the-clock bodyguard for Franklin and his radio, it aroused suspicions. The Communists clearly wanted to know what messages ALEXANDER was sending to London – and what information, if any, it was getting in return. Franklin was careful to keep the FTP fighters out of earshot that afternoon when he cranked up the radio.

After finishing his transmission on a hilltop a couple of miles from the chateau, Franklin was surprised to see an enemy plane buzzing overhead. It was a Doënier flying boat, a French relic from the ‘20s that flew so low that Franklin got a good look at its crew. The plane was a surveillance craft that bore a resemblance to Howard Hughes’ “Spruce Goose” of yore. To Franklin’s eye, the Doënier didn’t appear to have any machine guns or bombs aboard.

Still, the plane’s presence spooked Alsop and his team. It may have meant the Germans had zeroed in on ALEXANDER’s radio transmissions and were planning an attack. Alsop ordered his mates to pack up and shift to a different FFI-friendly home. It was the first of ALEXANDER’s many moves from chateau to chateau.

In the weeks to come, the trio only sporadically slept outdoors. When they bunked under a roof, it tended to be in a big country house, as Alsop enjoyed pointing out in the years to come. Some of the homes were chateaux fermes, working farms that had been abandoned or stripped bare; others were opulent mansions still occupied by gentleman farmers and wealthy families.

Some owners were patrons of the FFI, while others were sympathetic to the Milice but kept their political views quiet, at least in the presence of ALEXANDER and company. On occasion the owners asked Alsop for reimbursement; he happily obliged, tapping the stash he brought with him from London. Others refused payment, telling Alsop they were honored to help and encouraging him to use his cash elsewhere. Team ALEXANDER christened their indoor accommodations “motels.”

One of the motels they stayed in on their way to Dordogne was a dilapidated joint that lacked running water or reliable electricity. The team was forced to bathe in a nearby creek and use a garden outhouse that was separated from the main home by a six-foot-high steel picket fence.

Franklin was using the privy late one August evening when the rat-a-tat-tat of small weapons fire suddenly erupted from the other side of the property. The radioman cursed at himself for leaving his rifle and sidearm in the big house. Holding his still-unzipped pants with one hand, he vaulted over the fence and barged into the house, which was in pandemonium.

As Franklin scrambled to corral his radio, Maquisards were yelling that there were Boche in trucks attacking from a road to the west. He quickly huddled with Alsop and Thouville. They agreed that Franklin and his wireless should run east, away from the gunfire, which is what Franklin did in the company of a local farmhand who doubled as a Resistance fighter.

Franklin carried the wireless while his companion grabbed Franklin’s M-1; the two of them ran full-tilt in pitch dark for a half-mile or more, through an apple orchard and up the side of a wooded hill before they dared take a breather. The firing receded, then stopped. Things stayed quiet.

Just as they began to relax, an Allied bombing raid could be heard, softly at first, then much louder and closer. The bombers were pounding an area immediately to the east – exactly where Franklin and his aide had been heading.

Even after the bombing waned, they continued to lie still, worried that Germans might be combing through the woods to catch stragglers. Finally, they made their way back toward the house, “weapons at the ready,” Franklin remembered.

It turned out to be a long and messy false alarm. Team ALEXANDER never got the complete lowdown, but apparently Maquis sentries had fired on an enemy truck that had, in all probability, blundered down the dead-end road to the chateau. The Boche had returned fire, at least for a time, as the truck reversed course. Maquisards, as was their wont, may have expended considerable energy and ammunition firing at phantom soldiers and vehicles.

Alsop and Thouville spent the bulk of the night at the base of the chateau, their rifles cocked westward.

The Jeds again huddled when Franklin returned. There was no rest for the weary. Alsop insisted that they resume the push toward Dordogne right away.

*

Just before sunup, Team ALEXANDER moved out in a Gazogene, cautiously, because they were using the same road down which the Germans had retreated a few hours before. Progress was slow. They had to probe their way through heavily forested areas.

Each time they came to a bend or a crossroads, they got out to conduct reconnaissance to make sure there weren’t any hostile forces around. To tide them over, they had packed cheese sandwiches and wine; as they slurped le vin, they were careful not to let the bottle top smash their teeth as the car jostled around.

At one point, they came across a tree that had been deliberately chopped down by the Germans to set the stage for an ambush. But no guerillas or soldiers were evident. Not far from the felled tree, they went looking for a Maquis ally whose hut was hidden in the woods. But when they got there, there was no sign of him; the shed was riddled with bullet holes, but they didn’t find any traces of blood. Maybe the Maquisard had eluded the ambush.

On the same trip, they ran into a German tank on a windy road along a hillside. The tank was able to get off only one shot; it missed, badly. Their Gazogene found cover and slipped up the hill. The tank did not pursue them.

Franklin’s radio gave up the ghost after another few days. Whenever they encountered another Resistance cell, they’d ask if a radio were available. Miraculously, one was – an old B-2 set that must have been supplied by the SOE earlier in the war. Just as miraculously, it still worked.

After three or four days of playing cat-and-mouse on the roads of south-central France, Team ALEXANDER arrived in Dordogne along the Brive-Périgeaux corridor in the department’s northern region.

Alsop had been advised by sources along the way that the Dordogne Resistance cell would be in the woods east of Brive. But when the ALEXANDER trio arrived, they learned that the Maquis men were in the middle of assaulting the German garrison in Périgeaux, some 25 kilometers northwest.

They hustled back onto the road, expecting at any moment to bump into pissed-off Wehrmacht grenadiers or weary FFI stragglers. Instead, they motored unimpeded into Périgeaux. The firefight, brief but bloody, had ended hours earlier. After abandoning the village, most of the Germans had fled north and west, toward the safety of their Atlantic coastal bases.

Team ALEXANDER joined a raucous liberation party in the town square fronting a 300-year-old cathedral. People were weeping with joy, celebrating the end of four years of Nazi oppression. Within minutes, Alsop, Thouville, and Franklin found themselves seated in the back of a brasserie, being plied with wine and beer – and getting smothered with hugs and kisses.

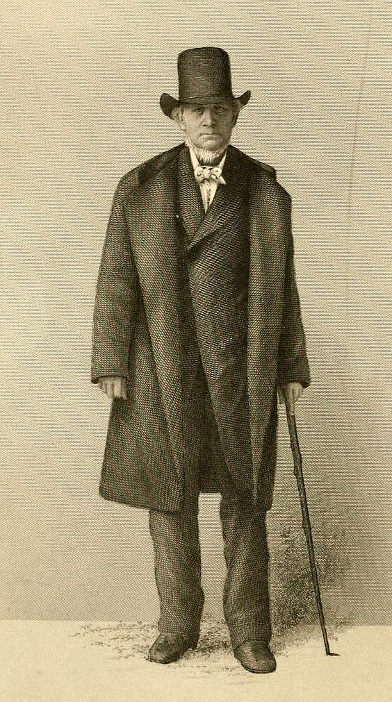

There they joined in saluting the man who had orchestrated the German ouster from Périgeaux. He was the most formidable Resistance leader they would encounter. His nom de guerre was “RAC,” a colloquial French acronym that meant, Franklin was told, something on the order of “feisty Scottish dog.”

RAC was the commandant of what was called in that part of Occupied France the AS, the Armée Secreté. His reputation was so fierce that the local Resistance cell was named in his honor, La Brigade du RAC.

RAC was small in stature but large in grit. He was quiet, “not given to talk,” Alsop remembered. The Frenchman’s eyes were cold and expressionless, like a cat’s, Alsop thought.

Early in the war, as a regular officer in the French army, he was captured after the Germans overran France, but managed to escape to Alsace-Lorraine. Not long after, he was recaptured by the Gestapo but again slipped away, this time to the heartland of France, where he organized his own Resistance brigade and quickly became the Germans’ Bête Noire.

Alsop would dub him Le Chat (“The Cat”); years later he called RAC the most courageous man he’d ever known. When Team ALEXANDER first met them, the Brigade RAC consisted of about 600 men. When ALEXANDER departed a few weeks later, the brigade had nearly doubled in size and was gaining new recruits every day. RAC was “hero-worshiped” everywhere he went, Alsop observed.

Discipline in the Maquis “was a matter of the force of human personality,” Alsop wrote in a Saturday Evening Post essay a quarter-century later. “Some Resistance groups, because that force was lacking, disintegrated. Not the Brigade RAC.”

RAC and his charges that afternoon had just sent the hated enemy packing; he and his guerilla fighters were being loudly fêted.

Profane shrieking suddenly erupted in the square. RAC and the Jeds hustled outside to check on the disturbance. Several hundred German prisoners were being paraded in front of the cathedral. Villagers were lining up to hiss and spit at them.

“Every (enemy) face had the same gray pallor,” Alsop recalled. From there, ALEXANDER was told, they would be taken to the railway yard where they would be lined up against boxcars and executed.

Alsop immediately voiced opposition. These were prisoners-of-war and should be treated as such, Alsop told RAC. It was clear from their appearance that the Germans were either too old, too young, or too infirm to be frontline soldiers, the American argued.

It was at that moment that “we were then further enlightened about the character of the enemy,” Franklin recollected.

A day or two before, the Maquis had entered nearby Saint-Martin-de-Pallières, a village that the Germans had just deserted. Hanging from the balcony of virtually every house were murdered townspeople, children among them. They’d been slaughtered because the local Resistance had been so effective in harassing the enemy.

The Jed team did not know whether to believe the massacre story and were never able to corroborate it. “But the point was that the populace believed it and they were demanding an eye-for-an-eye,” Franklin wrote. Lord knows there were enough true stories of Nazi atrocities; this one sounded credible to the Jeds.

Still, Thouville and Franklin lent their support to Alsop. The aging men and young kids being jeered were hardly the type to perpetrate war crimes, they echoed.

RAC and his compadres wouldn’t budge. Vengeance had to be carried out; their countrymen were demanding it.

Alsop firmly replied that the U.S. flag would have nothing to do with mass shootings. Team ALEXANDER packed up their equipment, climbed back into the Citroën, and headed toward Brive.

“Nothing that Stewart Alsop ever did made me more proud of him than that,” Franklin recounted in his memoirs. “Though the prospect of the massacre made me feel ill, I must say that I would probably not have thought enough about it, or taken such a stand, or carried the matter so far, had not Alsop led the way. . . I was also proud of Thouville. Though I cannot speak for what his thoughts may have been, his words and actions were entirely ALEXANDRIAN.”

The team never found out if the German stragglers had indeed been executed in Périgeaux. They chose not to ask questions for fear that members of the RAC Brigade or their ardent supporters might take offense. Instead, the three Jeds recognized the value of cultivating a close working relationship with RAC and his lieutenants. RAC commanded near-universal obeisance from the local populace.

The exception, of course, were the Communist guerillas in the FTP. Alsop, as he had been instructed at Milton Hall, attempted to broker a rapprochement between RAC and the FTP. He didn’t get far. The FTP at that point in the war was obsessed with settling old scores and seizing as much private property as they could from despised ploutocrates.

“Louis, the FTP leader, ‘yessed’ us to death but when it came time to act, FTP participation was minimal or nonexistent,” Franklin remembered.

RAC and Alsop agreed that their little army’s next objective should be the liberation of Angoulême, a town some 85 kilometers northwest of Périgeaux that straddled a key roadway to the enemy’s coastal garrisons. As they eyeballed a map, RAC told Alsop that it would take several days by car for his brigade to circumnavigate all the German troops along the way. But RAC knew of some friendly chateaux fermes where they could bivouac enroute.

Early in their trek to Angoulême, ALEXANDER ran into the remnants of yet another Jedburgh team, MARK, at a country home. They learned that their friend and colleague, Lieutenant Lou Goddard of the MARK team, had been killed a few days earlier when his parachute’s static line had faltered.

Just outside Angoulême, Alsop ordered the ALEXANDER team’s car to slow down as they passed a chateau near the road. A bunch of armed FTP fighters were milling about, looking menacing. Alsop and Thouville asked for a briefing and were told that the owner of the chateau had collaborated with the enemy; they planned to execute him on the spot.

Alsop and Thouville started pressing the FTP guerillas to produce evidence that the owner was in league with the Germans. Whatever they cited must have been weak; after ALEXANDER began challenging them, the Communist guerillas “skedaddled,” Franklin recalled.

The owner turned out to be Manouche, the Comte de Balincourt, a member of one of southwest France’s most prominent families. Had ALEXANDER not intervened, Manouche may well have been shot and his property confiscated. The grateful Manouche invited ALEXANDER to use his home as its base of operation for the assault on Angoulême.

Alsop and Thouville again ordered Franklin to stay at the house to protect the B-2. Off the two lieutenants went to help RAC plan and execute the attack. Soon enough, Franklin heard the retort of sharp gun- and mortar-fire. It sounded nasty, but in truth the Germans did not put up much of a fight before retiring toward the coast.

La Brigade du RAC benefited from a diabolical scheme that was apparently hatched in concert with clerics from the local abbey. Weeks earlier, a cache of weapons had been buried in Angoulême’s cemetery. The guns had been hidden in caskets and slipped past the Germans during funerals, then dug up by villagers when RAC’s guerillas were poised to attack. The cemetery weapons helped rout the enemy.

Thouville and Alsop watched, mesmerized, as a company of 300 Italian soldiers stationed on the periphery of town surrendered en masse, giving up all their weapons, including a coveted 20-millimeter cannon that RAC and his men could put to good use.

Manouche de Balincourt and Thouville became fast friends. For the entirety of ALEXANDER’s three-week stay in Dordogne, the Manouche made himself available to Thouville and company. He served as chauffeur, courier, chef, and scavenger, all the more remarkable since he spoke next-to-no English.

While they were bunking at the Manouche’s chateau, ALEXANDER finally received some acknowledgment from London – but it was in French, in response to a message Thouville had crafted. Their Jedburgh superiors conceded they didn’t have the “foggiest” notion as to ALEXANDER’s whereabouts or what they’d be up to – or that the team was no longer attached to BERGAMOTTE.

It flummoxed Alsop that London’s communications had been so slapdash. But once ALEXANDER figured out that there was a French speaker plugged into the other end of the radio, Alsop ordered all future messaging be done en Française. It worked – at least to a degree.

The Jedburgh high command continued to frustrate ALEXANDER; the team was incredulous that London was so sluggish in responding to their requests for additional arms and gasoline to be parachuted into Dordogne. But at least they were now getting some feedback. Since Franklin’s command of French still left something to be desired, Thouville often wrote out a script.

Weeks later, when Alsop was recalled (briefly) to London, he had a heated confrontation with the British Jedburgh officer who was supposed to coordinating ALEXANDER’s radio liaison. Franklin claimed that Alsop threw a punch at the Brit, but details of the tête-à-tête do not appear in Alsop’s memoirs.

For the next few days, the only time Alsop, Thouville, and Franklin fired their weapons was while hunting for ducks along the River Charente, hoping that the Manouche’s kitchen staff would turn them into dinner. After they found an old double-barrel shotgun collecting dust on the Manouche’s estate, they hunted rabbits, which were plentiful on the grounds. They also watched with dismay how farmhands produced the French delicacy foi gras.

While they had some down time, one of RAC’s followers told Franklin that the Germans were so desperate – and twisted – that they had begun parachuting soldiers disguised as priests behind Allied lines in France. A group of faux clerics had been apprehended because they were wearing jackboots underneath their monastic robes, Franklin was told. Other camouflaged German paratroopers had been more effective in infiltrating Allied areas, RAC’s lieutenant claimed.

“None of it seemed a very likely story at the time,” Franklin wrote years later. “I thought the Maquis was spinning a yarn or seeing ghosts.” But that was just weeks before the depth of Nazi depravity was exposed in the Battle of the Bulge. In the bedlam of the Ardennes Forest, the Germans unleashed assassination squads dressed as American G.I.s that inflicted horrific casualties. Before he left Angoulême for good, the RAC member gave Franklin a German Lugar pistol that purportedly had been taken off one of the priest-paratroopers.

The Germans that had been stationed in the Angoulême area, meanwhile, had taken refuge in their big bases near the ports of Royan and La Rochelle. Keeping their distance, the RAC Brigade and Team ALEXANDER holed up in a small riverside chateau outside Saintes and recalibrated their strategy.

RAC’s next objective was to expel enemy soldiers and sycophants from the town of Cognac, roughly halfway to the sea from Dordogne Nord. He asked ALEXANDER to help him plan and execute the assault. Again, the Jed trio found a chateaux ferme outside town. Thouville and Alsop helped themselves to copious amounts of the famous brandy that bore the town’s name; Franklin, not surprisingly, refrained.

At one point, the locals treated them to 140-year-old cognac that had supposedly been served at Napoleon’s coronation. To be diplomatic, Franklin took a couple of sips and could barely keep it down. Thouville and Alsop, on the other hand, imbibed freely. No one got drunk, but there was much knee-slapping, Franklin remembered.

Since at that point they were using a car fueled by alcohol, the trio actually poured “cheap” cognac into the gas tank!

Thouville invited his younger brother, Philippe de la Tousche, nicknamed “Philou,” to join them along the Charente. Enemy surveillance had deteriorated so badly at that point that all Thouville had to do to contact his brother was pick up a telephone.

Philou had no trouble finding their hideout. He was slender and handsome, like his older brother, but had no military training. Philou, therefore, was of little use in ambushes or sabotage missions, so RAC and Alsop assigned him to be Franklin’s go-fer.

The enemy was dug in so deep in Royan and La Rochelle that any direct assault would be foolhardy, RAC concluded. For several days running, Alsop had Franklin and Thouville send urgent radio messages begging London to send gasoline, supplies, and weaponry to RAC and his Cognac-stationed warriors. But they received nothing, not even an explanation, Franklin remembered. By now, the Maquis had no shortage of Peugeots, Citroëns, and Renaults; what it lacked was gasoline.

The weather, moreover, was turning colder. ALEXANDER had arrived in France wearing summer uniforms; they needed overcoats and warmer clothing. If they couldn’t get supplies from London, they reasoned, maybe they could wangle them from the nearest Allied army.

So Touville and Alsop borrowed a Gazogene, a guide, and a couple of RAC’s men and traveled north of the Loire, dodging German patrols and Milliciens. After a couple of harrowing days, they bumped into the southwestern edge of the Allied advance from Normandy.

Wary G.I. sentries escorted Alsop and Thouville to their commanding officer. Their “strange” request was then relayed up the chain to a rear-echelon lieutenant colonel.

Alsop, remembering his training as a King’s Royal Rifleman and momentarily forgetting that he was now in the U.S. Army, stamped his feet, stiffened his shoulders, brought the back of his right hand up to his forehead, and bellowed, “Lefftenant Alsop reporting, sir!”

Three decades later Alsop wrote in his delightfully piquant style, “The light colonel gave me a lynx-eyed look, taking in brother John’s ill-fitting and by this time bedraggled uniform. There had been reports of Germans being sent to France in imitation American unforms.”

“’Lootenant,’ he said, emphasizing the first syllable, ‘how come you got your bars the wrong way round?’”

“’Do I, sir? Sorry, sir,’ I said. What else was there to say?

“‘And how come you got your crossed rifles upside down?’

“’Sorry, sir,’ I said, nonplussed.

“The light colonel lifted his telephone and asked to speak to a counterintelligence unit.

“I had visions of being stood up against a wall, offered a last cigarette, and shot as a German spy.”

It took a few more calls, but counterintelligence confirmed Alsop’s bona fides as “one of those goddamn OSS screwballs!”

Despite the affirmation, Alsop and Thouville returned to Cognac empty-handed. It “violated policy,” they were told, for the U.S. Army to provide supplies or equipment to OSS commandos or Resistance cells without explicit authorization from above. The Army, moreover, didn’t have any extra winter clothing to share with Jed teams or Maquisards.

The lack of appropriate clothing would prove to be a significant factor in the slowdown of the Allies’ push into Germany, contributing to their struggles in the Battle of the Bulge that December and January. To stave off the cold, Franklin borrowed thick pants from a Frenchman and took to wearing multiple socks and a couple of shirts underneath his field jacket.

*

Members of RAC’s brigade brought to ALEXANDER rumors about a German vengeance weapon that was supposedly being tested near the seaside town of Royan. The device was known as the V-4 or, Rheinbote missile, a potentially deadly antipersonnel weapon that upon detonation would kill troops while leaving buildings essentially intact – something of a non-nuclear precursor to the neutron bomb of two generations later.

RAC’s men had learned about the V-4 from Polish slave laborers who had escaped from an enemy base. Some of the Poles said they’d been forced to help the Germans run experiments with the weapon; they were worried it was getting close to deployment.

When Alsop and Thouville passed word of yet another Nazi Vergeltungswaffe terror weapon up the chain of command, they got the impression that Allied officials, then ducking V-1 and V-2 attacks in London, were unfamiliar with it. The bosses demanded verification, but it was virtually impossible for the RAC Brigade or ALEXANDER to infiltrate the German coastal defenses.

As an alternative, Allied intelligence wanted the leader of the Polish slave laborers interrogated in liberated Paris and ordered ALEXANDER to bring him there. The man spoke little to no French and no German or English whatsoever, so he had to be questioned by a Polish speaker. Which meant that in late October ALEXANDER had no choice but to undertake another perilous cross-country trek through parts of France still occupied by the enemy. They borrowed a civilian car from RAC’s fleet and pressed Thouville’s brother Philou into serving as driver.

A couple of weeks earlier when Alsop and Thouville had traveled north of the River Loire seeking supplies, they were told there were no passable bridges. They ended up cadging a ride across the river with a military ferry.

In the interim, however, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had performed a miracle. Bombed-out bridges had been restored and temporary spans erected to handle jeeps, trucks, and tanks. When ALEXANDER and company arrived on the southern bank of the Loire at Tours, they were waved onto a temporary structure. But when they reached the opposite side, military policemen ground them to a halt.

The group’s decidedly “un-G.I.” appearance rankled Army MPs. After all, Alsop and his men were wearing a mishmash of uniforms and civilian garb, were driving a bizarre-looking civilian vehicle, had two guys in their party who didn’t speak any English (one of whom was Polish, no less!), and lacked written orders or credentials.

“They suspected we were German spies, but, just in case, they were afraid to throw us in a stockade,” Franklin recalled.

Instead, ALEXANDER was told to hang out on the north bank of the Loire for a couple of days until the Army could verify their claims. Along with scores of other Allied military personnel, they checked into a hotel that turned out to have a first-rate restaurant, a development that delighted Alsop and Thouville, both of whom had gold coins and leftover francs burning holes in their pockets.

Alsop put Franklin in charge of the Pole while they cooled their heels in Tours. It was easy duty for the radioman; for the first time in years, the Pole was sleeping in a comfortable bed and eating decent food; he was hardly a flight risk! Still, Franklin slept in the same room and never let the Pole out of his sight.

It took two-and-a-half days to iron out the Army red tape, but ALEXANDER was finally told to continue their journey to Paris. Once they completed the 250-kilometer drive, they dropped off the Pole for his V-4 interrogation – and never saw him again. They had no idea of what came of his allegations or whether Allied intelligence ever acted on them.

To this day, the V-4 remains shrouded in mystery, the subject of wild conjecture. Some scholars question whether it ever got beyond the planning or testing stages; others claim the Germans attempted to deploy it against Allied infantry in the siege at Antwerp in late ’44.

Whatever the reality, the V-4 came nowhere close to inflicting the damage wrought by its infamous cousins, the V-1 and V-2.

*

Dick Franklin fell in love with Paris during his extended stay in the war’s last fall and winter. He took in the can-can shows at Moulin Rouge, cultivated a taste for French cuisine, explored Rive Gauche and Montmartre (where he stayed in a flat), and most of the time didn’t need to worry about whether his radio was working.

In early November ‘44, OSS ordered Franklin to return to the Cognac area to bring the RAC Brigade and other Resistance fighters up to speed with the latest radio equipment. Philou Thouville agreed to transport Franklin southwest in a motorcycle with a sidecar. A few kilometers west of Versailles in a village called Trappe, the pair survived a violent collision with an Army truck.

Both were hospitalized; Philou with a broken leg, Franklin with head and internal injuries. It took several days for word of their infirmity to reach Alsop. He rushed to the hospital and was told the military had issued an incorrect cable to Franklin’s wife Susie saying that Franklin had been killed. It was almost impossible for a G.I. in France to send a telegram back home at that point in the war, but Alsop tapped his family connections and managed to convey this message to Susie: “DISREGARD PREVIOUS CABLE. FRANKLIN FOUND. NOT DEAD. ALSOP.”

Alas, Susie had not received the original cable, so Alsop’s telegram caused confusion and no small degree of anguish. Suspicious FBI agents knocked on Susie’s door, wondering what the coded word “ALSOP” meant. Since censorship rules prevented her husband from identifying his special ops boss by name in his letters, Susie had no idea where “ALSOP” came from. After a lengthy interrogation, the FBI concluded that Susie and her mysterious cohort did not represent a threat to national security.

Franklin recovered in mid-November. ALEXANDER was sent to maritime France for one final liaison mission with the Resistance. Outside the coastal village of Les Sable d’Olonne, they were thrilled to – finally! – witness an ALEXANDER-ordered supply drop hit the ground. The parachute drop included gasoline and weapons for the Maqui, as well as British Army Issue winter clothing. Franklin at last got the jacket and scarf he’d been requesting for weeks on end.

With most of the enemy racing for the border, the Jed trio’s shooting war was pretty much over as winter approached. Alsop was ordered to London in mid-fall ’44, where he assessed the Maquis’ strengths for his OSS/SOE/Jed superiors and (again?) may have tongue-lashed ALEXANDER’s communications liaison. He was then parachuted back into southwestern France for a short-lived reunion with RAC and other Resistance leaders. But by then most Maquis organizations were heavily armed and self-sufficient.

Alsop no longer needed to bounce from farmhouse to forest hideout providing a helping hand as he had that summer and early fall. Soon enough, he rejoined his team back in Paris; he and Franklin somehow managed to scare up a turkey to celebrate a belated Thanksgiving. After a couple more weeks counseling SHAEF on the efficacy of certain French Resistance cells and Jedburgh operations, Alsop flew back to London to continue his OSS duties.

*

Tish had suffered a miscarriage in late summer but Alsop’s brief visit to London that fall had resulted in a second pregnancy. The couple had already made plans for Tish to travel across the ocean solo, move in with Stewart’s sister and brother-in-law in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The only member of the Alsop family that Tish had met at that point was Stewart’s younger brother John, while he was in training with the Jeds.

Still a teenager, Tish was uprooting herself to live in a strange land surrounded by strangers. It could not have been easy, even for someone of Tish’s moxie.

*

There were Maquis activities in the winter and spring of ’45 aimed at hounding the retreating Germans and making life miserable for the enemy troops still holed up at the U-boat pens and Kriegsmarine bases on France’s Atlantic coast. But most Jeds were sent to the sidelines, recalled to Britain, or dispatched to the Pacific or Chinese-Burma-India theaters, among them John Alsop.

An exception was Richard Thouville. Thouville reentered the French Army in early ’45 but was sent back to the heartland to continue working with RAC. He stayed with RAC’s brigade almost until V-E Day in May of ’45 and continued to serve in the French Army after the war. He returned to his wife and children and stayed in touch with Alsop and Franklin over the years, exchanging letters and attending Jedburgh reunions in Europe and the U.S.

Franklin was recruited that winter by a special ops group examining the feasibility of sending paratroopers into Nazi-held territories to rescue Allied prisoners-of-war. There was great fear that POWs would be summarily executed as the Wehrmacht disintegrated and Allied troops penetrated deeper into the Reich. But Franklin and other convinced the brass that POW rescue missions – from the air – stood little chance of success. As it turned out, relatively few Allied prisoners were murdered in cold blood.

Eventually, Franklin returned to New Jersey and sought to take advantage of his expertise in intelligence and communications. In the 1950s, he accepted an offer to join the Central Intelligence Agency and stayed with the agency for the bulk of his career.

*

The pregnant Tish boarded a jam-packed freighter to travel across the Atlantic. It took her 19 days before the boat steamed past the Statue of Liberty. The Army and OSS acceded to Alsop’s request to join his wife in the States. Two weeks after Tish’s departure, Alsop got a berth on the Queen Elizabeth. Soon they were reunited, at first in New England, then in D.C.

As the decades went by, the Commandant Americain was good about staying in touch with his old KRRC and Jedburgh mates. In 1955, the Royal Couple attended a reception to honor the KRRC; Stewart and Tish traveled to London for the occasion and had their pictures taken with Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip. Five years later, there was a New York reunion of the American, Canadian, and British KRRC alums. George Thomson, Ted Ellsworth, and Tom Braden all joined Alsop in a night of storytelling and merriment. There was also at least one trip to France to retrace ALEXANDER’s steps with the RAC Brigade.

In July of 1971, Alsop was taking out the trash at his country home in Maryland when he suddenly felt tired and nauseous. He sensed something was wrong and found himself muttering the same phrase he used 27 years earlier when he prematurely bailed out of a British warplane over Occupied France: “Face it, Alsop. You’re in trouble.”

He was. Alsop had contracted acute myeloblastic leukemia, a rare cancer of the blood‐producing marrow. After a three-year battle that produced a poignant memoir, Stay of Execution, Alsop succumbed. A few weeks earlier he had written, “A dying man needs to die as a sleepy man needs to sleep, and there comes a time when it is wrong, as well as useless, to resist.”

He was tragically young – barely 60 when the end came. At the time of his diagnosis, the two youngest of his six children were only four and 11. Tish was widowed at the tender age of 48.

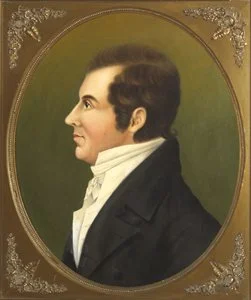

Stewart Alsop remains, a half-century after his passing, a pivotal figure in postwar American journalism and foreign policy. Together with his older brother (and fellow columnist) Joe, he helped forge the Georgetown Set, the elite cadre of Washington opinion leaders who sought to reverse America’s traditional isolationism and harden the country’s resolve to wage and win the Cold War.

For good or ill, the Alsop brothers and their vaunted (and often feared) Sunday night dinner/salons with Cabinet officers, Members of Congress, and presidential wannabes shaped U.S. national security policy for two generations. Tish often served as a hostess at these gatherings, usually at her brother-in-law’s Georgetown townhouse.

The Alsop brothers were writing partners from 1945 to 1957; at its zenith, their column, “Matter of Fact,” appeared in nearly 150 U.S. newspapers. Twice awarded the Overseas Press Club medal for international reporting, the Alsops had a hard-and-fast rule: never to write about a country unless they had personally visited and gotten to know its leaders.

After he broke away from his brother, Stewart Alsop’s columns for the Saturday Evening Post and later his back-of-the-magazine essays for Newsweek were among the era’s most influential commentaries. Unlike his sibling, whose hardline views became increasingly shrill and combative, Stewart addressed weighty matters in a nuanced and almost wistful tone. He abhorred heated rhetoric and ideological rigidity, whether it came from the left or right.

When 1968’s Tet offensive exposed the frailty of America’s policy in Vietnam, Stewart eventually joined Walter Cronkite and other pundits in urging an end to U.S. combat involvement, pointing out the futility of sustaining an unpopular and ineffectual war. In contrast, the elder Alsop doubled down on his conviction that victory in Southeast Asia was just around the corner – bluster that, five-plus decades later, still clouds Joe’s legacy.

Throughout their careers, both brothers remained intimately connected to the intelligence communities of the U.S. and its allies – perhaps too intimately.

Five years before his death, Stewart Alsop wrote a piece for Newsweek entitled, “Yale Revisited.” In it, he deplored the contempt with which many college-age people treated the U.S. military and other institutions. But he also volunteered: “There's something going on here our generation will never understand.”

The “fraudulent” military draft system, he argued, coupled with the deceit that undercut our presence in Vietnam, had convinced certain young people that the American system was “a gigantic fraud.” Many journalists of Alsop’s era, including his own brother, were incapable of acknowledging such uncomfortable truths.

Tish, the onetime decoding specialist, had to endure a lifetime of Alsop-ian intrigue that permeated her homes in Georgetown, Cleveland Park, and backwoods Maryland. Her daughter Elizabeth, now a noted children’s author, chronicled her bumpy childhood and her mother’s struggles with depression and substance abuse in Daughter of Spies.

Tish Hankey Alsop lived for nearly four decades after Stewart passed. She died in 2012, the mother of six, grandmother of 15, now a great-grandmother many times over. It had been 70 years since she sparked their romance by telling her future husband that his military haircut made him look like a criminal.

In the final pages of Stay of Execution Alsop wrote of his OSS heroics, “There were a few moments of fear, exhaustion, and even some danger, but for the most part those weeks in the Maquis were a lot of fun – in some ways the best fun I’ve had in my life.”

He recalled that a few weeks after he returned to the U.S. in 1945, he got a package in the mail postmarked Paris. It turned out to be a “handsome scroll” awarding him a Croix de Guerre avec Palme, Signé, Charles de Gaulle.

His old pal Thouville had written the citation: “S’est trouvé de nombreuses fois dans les situations les plus périleuses d’où il s’est toujours sorte avec une calme edifant et une volunté galvanisante les énérgies de tous ceux qui l’entourait.”

“I cannot boast that my calm is edifying nor my will galvanizing, but my situation is undoubtedly again a bit perilous,” Alsop wrote in his self-effacing way as the end approached.

“I came out of that peculiar experience all in one piece, and maybe I will again. Even if my stay of execution turns out to be a short one, I have reason to be grateful, for a happy marriage and a reasonably long, amusing, and interesting life.”

# # #

Timothy M. Gay is the Pulitzer-nominated author of two books on World War II, two books on baseball history, and a recent biography of golfer Rory McIlroy. He has written previous WWII-related articles for the Daily Beast, USA Today, and many other publications.