Josephine Butler was a British 19th century social reformer and feminist activist who was certainly ahead of her time. Here. Nancy Bernhard explains the impact that Josephine had across several social areas.

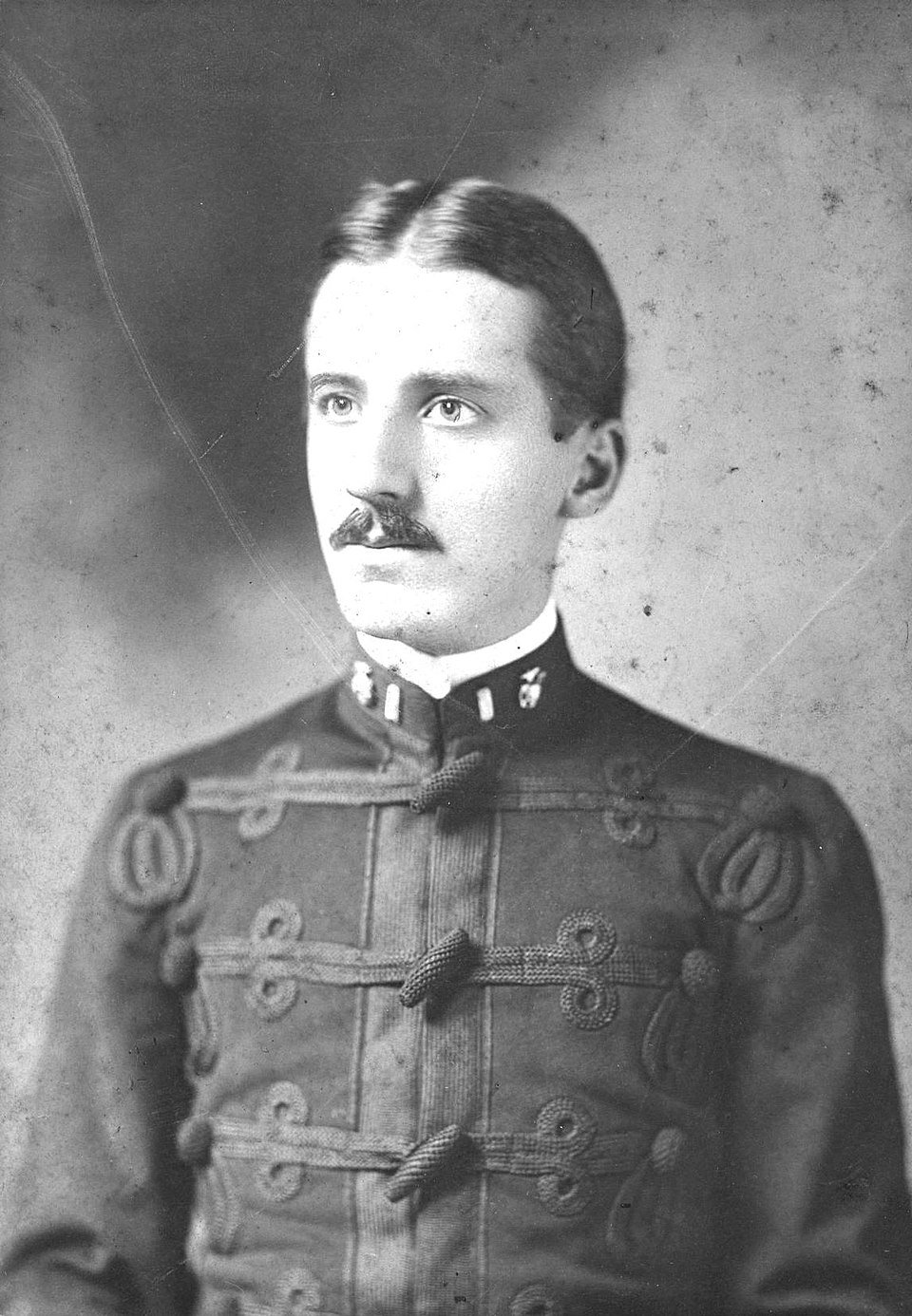

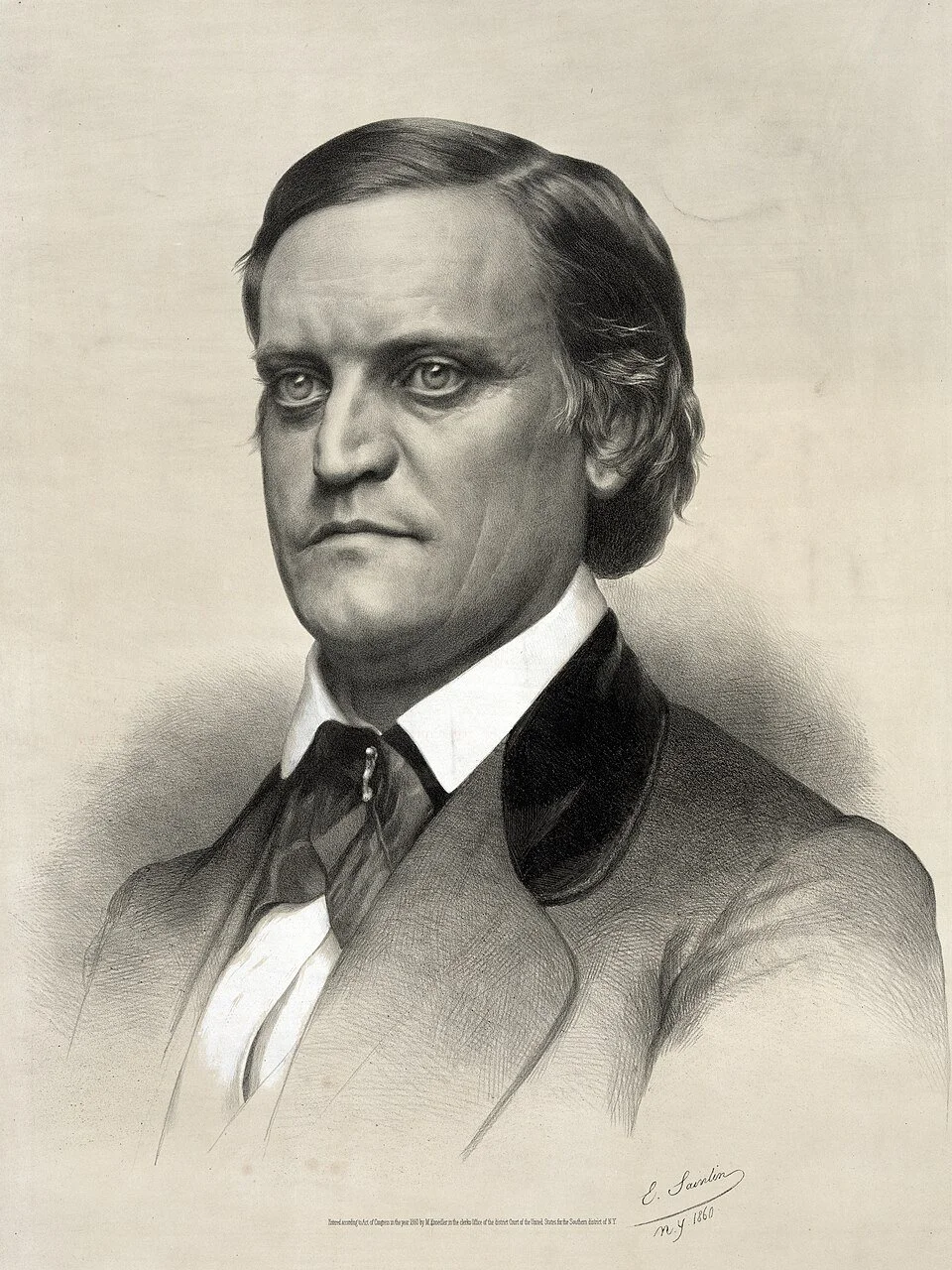

Josephine Butler, circa 1876.

In researching the 19th century New York sex trade for my historical novel The Double Standard Sporting House, I encountered two varieties of religious reformers who addressed the so-called “Social Evil.” In the aftermath of the Civil War, conservative and evangelical Christians turned their attention to “fallen” women, and tried to persuade them to repent, and to resist sexual temptation. These efforts hardly ever succeeded, because the reformers misunderstood the reasons why women did sex work. In a time when they were excluded from virtually all well-paid employment, it was a last-resort means of survival. It was also the only choice open to victims of rape and sexual assault, shamed and excluded for the behavior of their predators.

But not all reformers were so eager to blame the victims, and directed their redemptive efforts at the customers, procurers, and pimps of sex workers. Rather than shaming girls, this kind of activist offered them job training, housing, and work that paid a living wage as avenues out of the trade. These practical and compassionate reformers changed many women’s lives. In the US, the Female Moral Reform Society, originally constituted in the 1830s and revived in the late 1860s, even tried to criminalize the hiring of a prostitute in New York State. Given that the Tammany Hall political syndicate controlled New York’s politics top to bottom, that proposed legislation did not get very far. But these progressive reformers began to shift moral blame for the Social Evil off powerless girls and onto their exploiters.

Daring to Stoop

Perhaps the most inspiring and clear-eyed anti-prostitution reformer of the Victorian era came from the far north of England. A beautiful Englishwoman of good family and education, wife of a university don, Josephine Butler had always been a charitable Christian. But after the accidental death of one of her four children and her only daughter, she became an extraordinary activist. Resolving to help people whose pain was greater than her own, she sat with prisoners in the workhouse, and brought dozens of prostitutes, often dying from venereal disease, into her own home. She campaigned for women’s suffrage and against child trafficking, tirelessly mobilizing her faith and gentility on behalf of Britain’s most neglected and abused women. Clergyman and reformer Charles Kingsley said in 1853 that the in the cause of fallen women, “What is required is one real lady who would dare to stoop.” Butler soon became that lady. Florence Nightingale thought her “touched with genius.”

Understanding sex work to stem from evil economic conditions and the absurd subjugation of women, Butler wrote, “The prostitute sees herself as the only realist in a world deluded by moral hypocrisy.” She built a series of Industrial Homes where girls could learn trades that would support them. She campaigned for better work and educational opportunities for women, but also for better treatment in the workplace, as girls were often assaulted by their employers and then barred from employment. She also organized against couverture, the policy that saw women’s rights revert to their husbands upon marriage.

The Contagious Diseases Acts

Butler gained national fame when she fought the Contagious Diseases Acts, passed in stages by Parliament during the 1860s, allowing police to detain and physically examine any woman in the vicinity of a military installation. Many poor women were subject to internal examinations by fiat. Butler called this ‘steel rape.’ No men were ever harassed or even questioned for frequenting sex workers, as the law was designed to protect them but not women from disease. For pointing this out, Butler was often threatened, and she was badly beaten more than once. A building where she was speaking was set on fire.

While Butler persuaded many people of the one-sided injustice of the Contagious Diseases Acts during her years-long campaign, the Conservative government failed to repeal them. One observer quipped, “Hell knows no fury like the scorn of a man who has been humiliated in debate by a sexually attractive woman.” In one year, Butler gave 99 speeches. A Member of Parliament remarked: “We know how to manage any other opposition in the House or in the country, but this is very awkward for us—this revolt of the women. It is quite a new thing; what are we to do with such an opposition as this?” The Acts were not repealed until 1886.

Against Child Trafficking

In the 1880s, Butler also began a long and contentious campaign against child trafficking. She joined forces with crusading journalist William T. Stead and members of the Salvation Army to draw attention to the abduction and sale of English children to European brothels specializing in pedophilia, and to pass a law stalled in the House of Commons raising the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen.

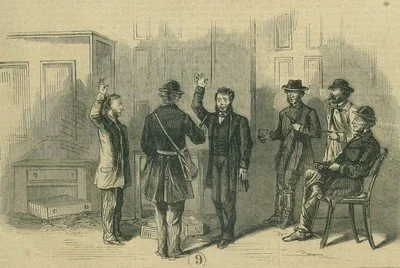

Butler and Stead’s “Special and Secret Committee of Inquiry” made a plan to purchase children themselves, to show how easily it could be done. For ten days in London, Butler and her eldest son posed as a brothel keeper and a procurer, and bought time with children in elite brothels, paying a total of one hundred pounds for ten different girls. They passed their information to Scotland Yard, and arrests ensued.

Stead, through Butler protégé Rebecca Jarrett, contracted to buy the virginity of Eliza Armstrong, the thirteen year-old daughter of a destitute sex worker. The girl was instead removed from her precarious life and adopted by a Salvation Army-affiliated family in France. Stead published an eye-popping five-installment account of his purchase in the Pall Mall Gazette under the title “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,” hearkening to the Minotaur’s sacrifice of virgins. The series became a wild sensation, provoking intense public debate and widespread demonstrations, news sellers storming the paper’s offices for more copies. Parliament rushed to raise the age of consent.

But despite outspoken support from religious leaders, Stead and several of his co-conspirators were indicted for the abduction and procurement of Eliza Armstrong. Her mother now claimed she thought she was sending her daughter into domestic service, and her father had not been consulted. Rival newspapers tried to discredit Stead and steal his thunder. He served three months in jail, and Rebecca Jarrett served six. Butler was questioned but not charged. Though messy and sensationalist, the Maiden Tribute brought child trafficking into wide public notice for the first time, and legislation against it began in earnest.

God and One Woman

After her husband’s death in 1890, Butler slowly withdrew from public life, and died in 1906 at the age of 78. In 2005, Durham University named a residential college for her.

Perhaps Josephine Butler’s greatest achievement was to lay bare the hypocrisies of Victorian society. Her poise and respectability lent credibility, and her faith lent clarity. She said, “I plead for the rights of the most virtuous and the most vicious equally.”

Over decades she attacked the sexual double standard, writing, “A moral lapse in a woman was spoken of as an immensely worse thing than in a man, there was no comparison to be formed between them. A pure woman, it was reiterated, should be absolutely ignorant of a certain class of evils in the world, albeit those evils bore with murderous cruelty on other women.” She began to shift public perception of a sex worker from a guilty, sinful temptress to a person who was victimized by a morally inexcusable society, and inspired a generation of activists in Europe and North America, including in New York, where some of the characters in my novel try to follow her example.

Her favorite phrase was, “God and one woman make a majority.”

Nancy Bernhard’s historical fiction debut, The Double Standard Sporting House, was recently released.

References

Helen Mathers, Patron Saint of Prostitutes: Josephine Butler and a Victorian Scandal, The History Press, 2014.

Glen Petrie, A singular Iniquity: The Campaigns of Josephine Butler, The Viking Press, 1971.

Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America, Oxford University Press, 1985.