The American Civil War still fascinates the public mind for its timeless reminder of when our politics were truly at their nadir. Despite some contemporary warnings about a national separation, fortunately no such moment has come to pass since the cannons ceased and the muskets were put down in 1865. Intense vitriol and hatred over the state of this country is something no specific to the war period. Whether it be 1860, 1828, or the 1800 election that saw friends become bitter rivals in outgoing President John Adams and incoming President Thomas Jefferson cease communicate for several years, national politics endures as a nasty business.

Yet, in our memory of the Civil War and its causes, we tend to let the latter fall by the wayside, consequently forgetting how unique those divisions were in the 1850s, culminating in southern secession in December 1860 after President Abraham Lincoln’s victory. Slavery was the cause as evidenced by the declarations from the southern states[i], but how many grasp slavery as the sectional issue that it was? Where does sectionalism fit into our memory? Without a more holistic understanding of the war through the sectional crisis that preceded it, we let more simplistic interpretations of why it started take over.

Sam Short explains.

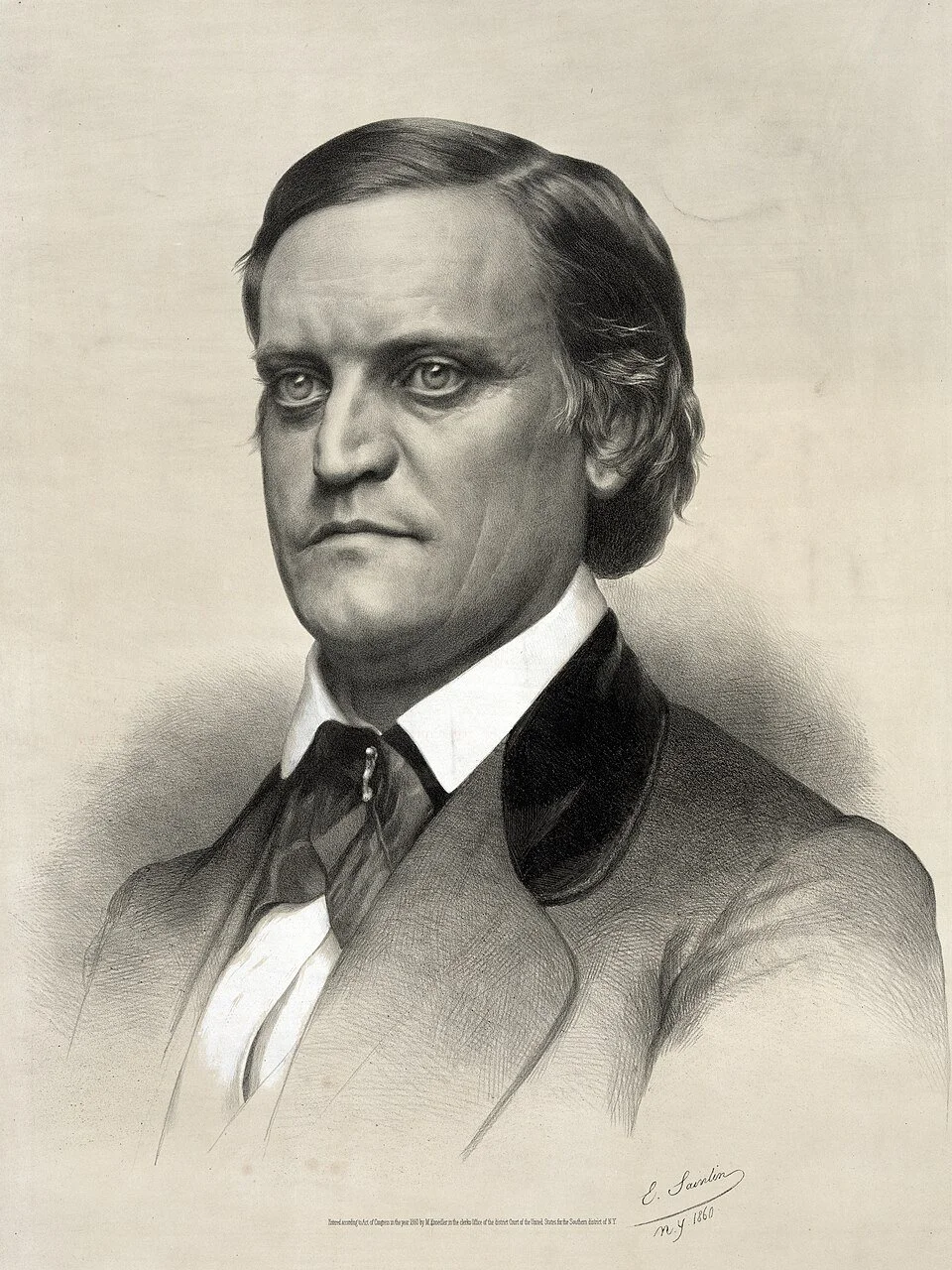

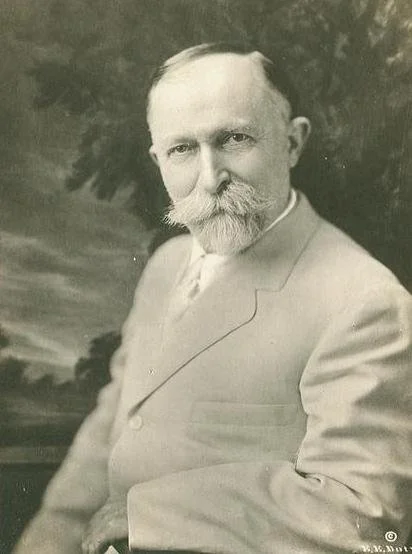

John C. Breckinridge in 1860 by Jules-Émile Saintin

Defining Sectionalism

What is sectionalism and why is the period preceding the war defined as the Sectional Crisis? To answer that question, it is important first to define a section. As Professor Richard Bensel puts it, a section is a, “major geographic region.”[1] In this context, the sections that fought would be the North and South. Sectionalism, then, is the unique culture and economic tendencies emerging in those regions that create a politics of their own. A sectional politics does not have a national vision – one for the country as a whole – in mind, but whatever agenda best serves this cluster of states. The Civil War is a war between North and South, but just as accurately, a war of sections. It was not so simple as to say Republicans and Democrats fought with the former looking to limit slavery’s spread and the latter seeking to keep it.

The Sectionally Divided Democrats

The Democrats themselves were divided over the issue of slavery. In 1860, Southern Democrats did not feel enough assurance was given by candidate and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas that their institution would be defended. They opted to nominate their own candidate, Vice President John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky. The electoral map speaks to this division with the southern states going for him.[2] When looking at a breakdown of the popular vote, the University of Richmond does not record a single vote for Douglas in the southern state of Texas.[3]

Looking further back, divisions among Democrats over slavery preceded the Sectional Crisis as is exemplified by the Wilmot Proviso. Democratic Pennsylvania Representative David Wilmot introduced a proviso to President James K Polk’s $2 million appropriations bill allocating funds to negotiations with Mexico. This was August 8, 1846 during the Mexican-American War. In that proviso, Wilmot proposed,

as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them, and to the use by the Executive of the moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted.[4]

This was effectively Northern Democrats telling their southern colleagues they would not tow a line for slavery only for the sake of party unity.[5] Democrats did not have a pro or anti-slavery platform. They struggled to unify under one position towards the issue.

Geography and Politics

To be sure, from its inception, the Republican Party was northern-based. Multiple southern states did not cast a single vote for their candidate John C Fremont in the party’s first national election, the Election of 1856.[6] The North was not entirely Republican, but the Republicans were – almost – entirely in the North. In the modern era, parties have their strongholds. Democrats do better in New England, other coastal areas, and urban centers while Republicans capture the South and Midwest. Geography does correlate to politics on the electoral map and that observation largely holds true in our elections, but the question during the sectional crisis was not one of partisanship, but of sectional allegiances. For Southern Democrats, never mind where their northern brethren were heading, as they assessed the situation, they needed to make their own way.

An emphasis on the sectional dimension of this conflict dispels later assertions that the Democratic Party was the party of slavery. Southern Democrats supported it, but sectional divisions fly in the face of an argument for party unity. Studying sectionalism leaves us with a complex web of geopolitically motivated behaviors and allegiances that historians strive to make sense of in forming a metanarrative for the war’s causes. Studies are made more complicated when considering examples out of the South that push back against the conclusion of consensus being for slavery and against Lincoln. How are we to regard President Andrew Johnson, who, as a congressman from Tennessee – and Democrat –, was the only senator from a seceding state to remain in the Union? This is a man who historians studying his life have admitted it is hard to arrive at any definitive statements about when looking at his character.[7] More broadly, estimates say 100,000 men living in the Confederate states served the Union during the war.[8] Among them, Virginia-born Union General George Thomas, a slave owner before the war, alienated his family who refused to speak to him for fighting against the South.[9]

In history or contemporary politics, neat and tidy conclusions about politics, allegiances, or where one falls of the political spectrum for their views on divisive issues are few and far between. If we are to understand political history, we must understand in our analyses that single-dimension modes of thought with the left against the right or Democrats against Republicans runs the risk of obfuscating more intricate fissures that account for, in the case of the Civil War, sectionalism. In its only through the study sectional divisions that we see the clearer picture.

Did you find that piece interesting? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

[i] See “Avalon Project - Confederate States of America - Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina From the Federal Union,” n.d. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp.

[1] Richard F. Bensel “Sectional Stress & Ideology in the United States House of Representatives.” Polity 14, no. 4 (1982): 657–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/3234469.

[2] “Electing the President,” n.d. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/electingthepresident/popular/map/1860.

[3] “Electing the President,” n.d. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/electingthepresident/popular/map/1860/TX.

[4] “Wilmot Proviso, 1846,” 1846. https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1846WilmotProviso.pdf.

[5] David Wilmot et al., “Wilmot Proviso,” n.d., https://www.latinamericanstudies.org/mex-war/wilmot-proviso.pdf.

[6] “Electing the President,” n.d. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/electingthepresident/popular/map/1856.

[7] Rable, George C. “Anatomy of a Unionist: Andrew Johnson in Tne [sic] Secession Crisis.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 32, no. 4 (1973): 332–54.

[8] Carole E. Scott, “Southerner Vs. Southerner: Union Supporters Below the Mason-Dixon Line - Warfare History Network,” July 12, 2022, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/southerner-vs-southerner-union-supporters-below-the-mason-dixon-line/.

[9] Christopher J. Einolf, “George Thomas,” June 2012, https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/assets/files/pdf/ECWCTOPICThomasGeorgeHEssay.pdf.