Museums are important in helping us connect with the past and with historical events – but not all museums are equal. Here, Shannon Bent explains why she thinks Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker in the UK plays a chilling but important role in teaching and reminding us about the Cold War – and the power of nuclear weapons.

This follows Shannon’s articles on Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie (here) and Topography of Terror (here).

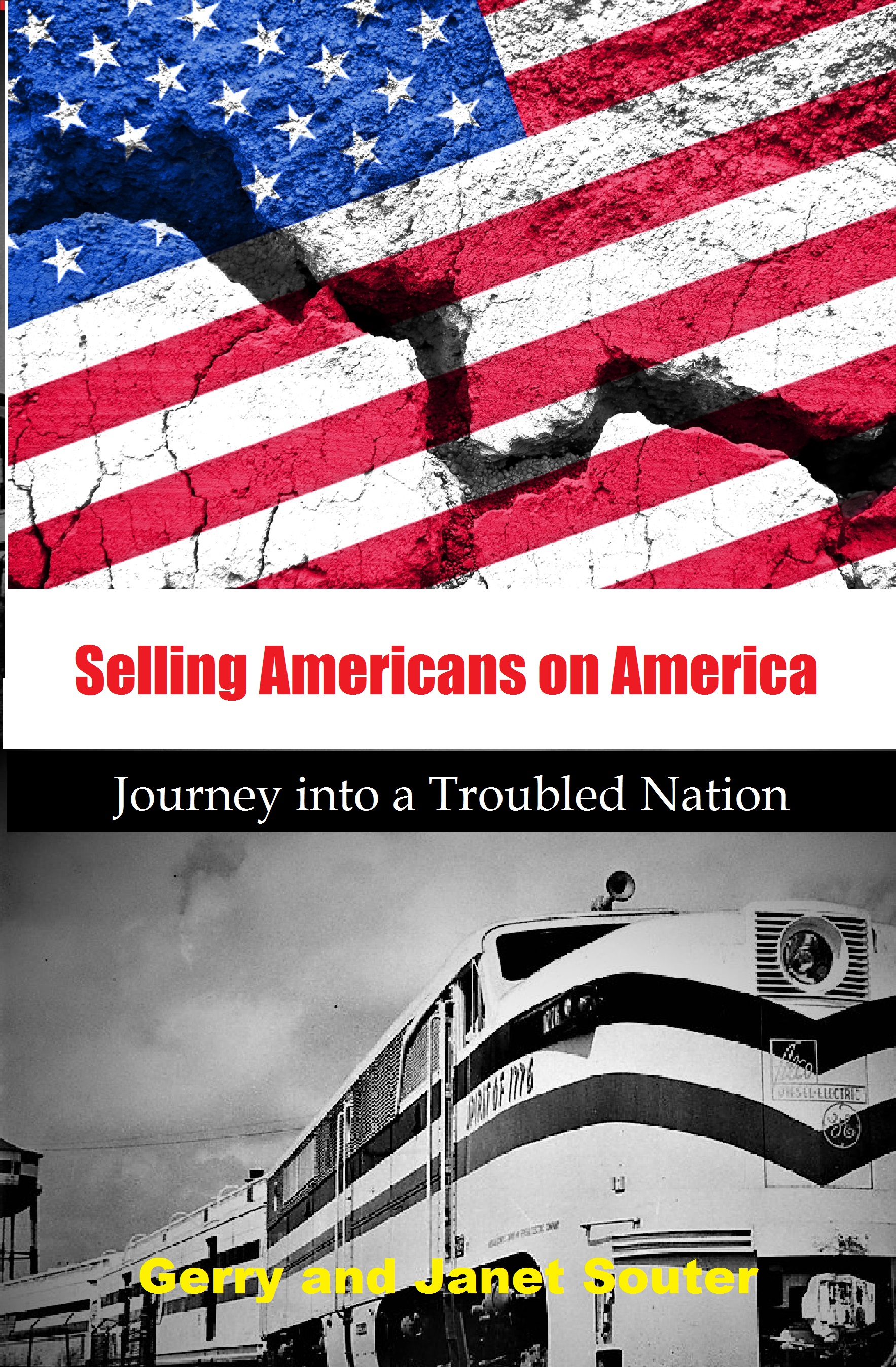

Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker. Source: Espresso Addict available here.

I’ve been studying history for quite a while now. I am only 22, yes, but if you count school and the years I spent doing exams, plus my nerdy extra-curricular research and reading, I’m fairly well versed in the general history of the world. I studied war specifically for three years and like to think I am continuing to each day with my work and personal reading. There isn’t much about war that scares me anymore, besides perhaps a gas mask which I do not wish my eyes to linger on for long; a fear born out of an episode of TV show Doctor Whoback in 2006. But aside from irrational fears made from fiction and exacerbated like a child’s head does, there aren’t exactly many elements of war left that give leave that sick, anxious feeling in my stomach. Many would call it desensitisation, and I am inclined to agree to an extent. Being exposed to images of the trenches, the Blitz, the Holocaust, time and time again, I guess I would have to agree the actual images start to lose an impact. Never the meaning though, and what it represents. The day I no longer find the thought of these events appalling is the day I want someone to fire me from the sector, because from that moment on I would consider myself useless.

Changing Warfare

However, in defence of the desensitisation argument, I would also argue that these elements of war perhaps do not scare me because I am aware they will never be repeated on a major scale. Never again will a world war be fought on soil, with soldiers dug in shelling each other across an empty space of land that belongs to no man. Never again will two countries bomb civilians in a tit for tat fashion to break morale. War doesn’t work like this anymore. The next major war won’t be fought with boots on the ground, with an occupying force in a country, or with the movements of heavy weaponry. The world faces a far worse fate than that. Total war has been replaced by the potential for total annihilation. Nuclear war is now the only warfare left on the cards, and the only element of conflict that terrifies me to my core. Why? It will be the most catastrophic thing the world has ever seen. Correction; the world won’t see it. Because there won’t be a world left, just by sheer nature of the implement.

Now this may all seem very dramatic and like I am scare-mongering. And I’ll admit, to an extent I am. Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD theory, is the best thing to come from nuclear weapons and makes me 90% sure the world is safe for a little longer. This concept states that while two opposing countries both hold nuclear weaponry, they will never fire upon the other, for the second they do, they will also be fired upon themselves, therefore destroying themselves. The fear of what it will do to them and their own people prevents them from inflicting it upon others. Kind of scary, kind of neat. I suppose if the world must have nuclear weaponry then let us kept this mind set flowing amongst as many countries as possible. It will keep us safe for now. But there are constant reminders of how close we have already come to utter decimation.

Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker

There is a bunker, mostly in the middle of nowhere, near a town called Nantwich in the UK. This bunker is known as Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker. And yeah, not so secret. But that’s the beauty of it. This bunker was to be one of a network across the UK that would have taken politicians and other groups of vital and important people into them upon the event of a nuclear attack. The bunker is mostly in the state it was left in; room after room of technical equipment, radios, med bays, shelters. It really is the perfect step into the past, specifically back to around 1962 and the event of the Cuban Missile Crisis; the moment the world held its breath and nuclear war was an inch away from actually happening. This event, in comparison to many parts of major warfare, is fairly recent history. My dad was five at the time. That isn’t all too long ago! My grandfather was part of the Royal Observer Corps, and his job was to effectively be waiting and looking out for the nuclear missiles that could come the way of Great Britain. Not that my dad knew it at the time, but the days of October 16thto October 28th1962 must have been some of the most stressful days of my granddad’s life. For him and hundreds of thousands of other people across the world, of course.

The Cuban Missile Crisis began when Soviet Russia placed armed nuclear missiles onto the island of Cuba, then run by Fidel Castro. America’s answer to this was to blockade Cuba and demand for them to be removed. What followed was probably the most tense 13 days of President Kennedy’s life as he tried to negotiate these missiles off the island.

The range of the missiles covered nearly the entirety of America. And let’s face it, with the way nuclear weaponry works, even areas outside of range weren’t exactly safe! This was the closest that the world has ever been to full out nuclear war. If the US had been fired upon, it would have retaliated, and chances are the UK, due to treaties and agreements, would have followed suit. We would’ve been looking at full world destruction in seventeen minutes. That is the closest the world has come to full destruction. That we know of at least. I won’t go into all the conspiracy theories on the number of times something similar has happened since and we have never been told about it, because we would be here all day. But that’s exactly my point. The reason this topic and this type of warfare still has the ability to scare me so much is because it could still happen. We have some pretty mad and unpredictable leaders out there at the moment. Trump, Kim Jong-un, Putin. They’re erratic and power crazy; I feel like if they were bought the wrong type of eggs for their breakfast in the morning, by 11:30 they would’ve decided to launch a nuclear weapon at the country their chef was from, providing it wasn’t their own of course.

The Realities of Nuclear War

And this is what Hack Green so chillingly brings to life. From this museum you can begin to understand the conditions that people worked in - underground for days on end without seeing daylight. You squint when you walk out at first, after having spent at least four hours in a concrete box with no windows. This museum also provides a fantastic element of fear to the proceedings, without being ‘cheesy’ or ‘crude’. They have ghost walks, and these are rather popular, but sometimes you can’t blame a site for capitalising on its theme. The element of fear it brings to the everyday visitor, however, is far more subtle. In the background there are multiple warning alarms and sirens going off. Occasionally an announcement will sound for everyone to take shelter. The control rooms house radar and machines that ominously bleep. Geiger counters crackle threateningly in the distance. This exceedingly clever atmospherics is something that many museums are now beginning to adopt; adding in those noises that people would’ve heard every day they were there, bringing their world to yours. One room in the bunker is a sort of cinema room, and in here they show the BBC’s Threadsfrom 1984. This is the definition of chilling; a film set during the nuclear apocalypse of Great Britain and details what would happen to the population. I would highly recommend checking it out (Amazon US| Amazon UK)

Witnessing the implications of what these people were working on through visuals only adds to the tension of the place. Perhaps one of the key aspects of the bunker is the bomb shelter, a room with the full sirens and noises of lighter bombing. However, every few minutes they simulate the noise of the nuclear bomb falling. This near as damn stops your heart. Obviously, the noise level is replicated to a safe point, (no ear drums are hurt in the duration of the simulation) but that only makes you more aware of the earth-shattering noise that would have been experienced. It really gives you a jolt. You then step back out, and in perfect curation style, you continue your journey around the museum to discover what would have happened post-bomb. This genius way of subtly taking the visitor around a timeline as if you were a member of the workforce in the bunker having to combat the issues faced gives a fantastic immersive experience. The museum is everything a museum should be; giving you a reality check about your own life as you experience, just for a moment, someone else’s.

Conclusion

I have to admit, I left with a rather sick feeling in my stomach. It was a hot day and the light was blinding as we walked out. I got in the car and looked back at the imposing yet unassuming structure of the bunker and thought ‘one day everything I’ve just seen from history could be a reality’. Einstein once said, in the perfect eloquence he always had; ‘I do not know with what weapons World War Three will be fought, but World War Four will be fought with sticks and stones.’ Hack Green beautifully (perhaps a bad choice of adjective, but you follow my point) presents what will happen before those sticks and stones. It gives a brilliantly immersive reality to those that wish to understand just how much of a knife edge we once sat on, and continue to, in my opinion. Take a deep breath as you enter though; the inspired curation and presentation of this museum serves as a stark reminder of the power we hold against each other. Hack Green in essence masters what science has still failed to achieve; time travel. But perhaps not just the past, maybe the future too.

What do you think of the article? Have you visited any nuclear bunkers? Let us know below.