Politicians have a history of using fear to gain votes and win elections. Here, Jonathan Hennika (his site here), considers recent events in the US in the context of 19th century America. He explains how immigrants from Ireland and Germany led to fear and the rise of the American Party – or Know Nothing Movement.

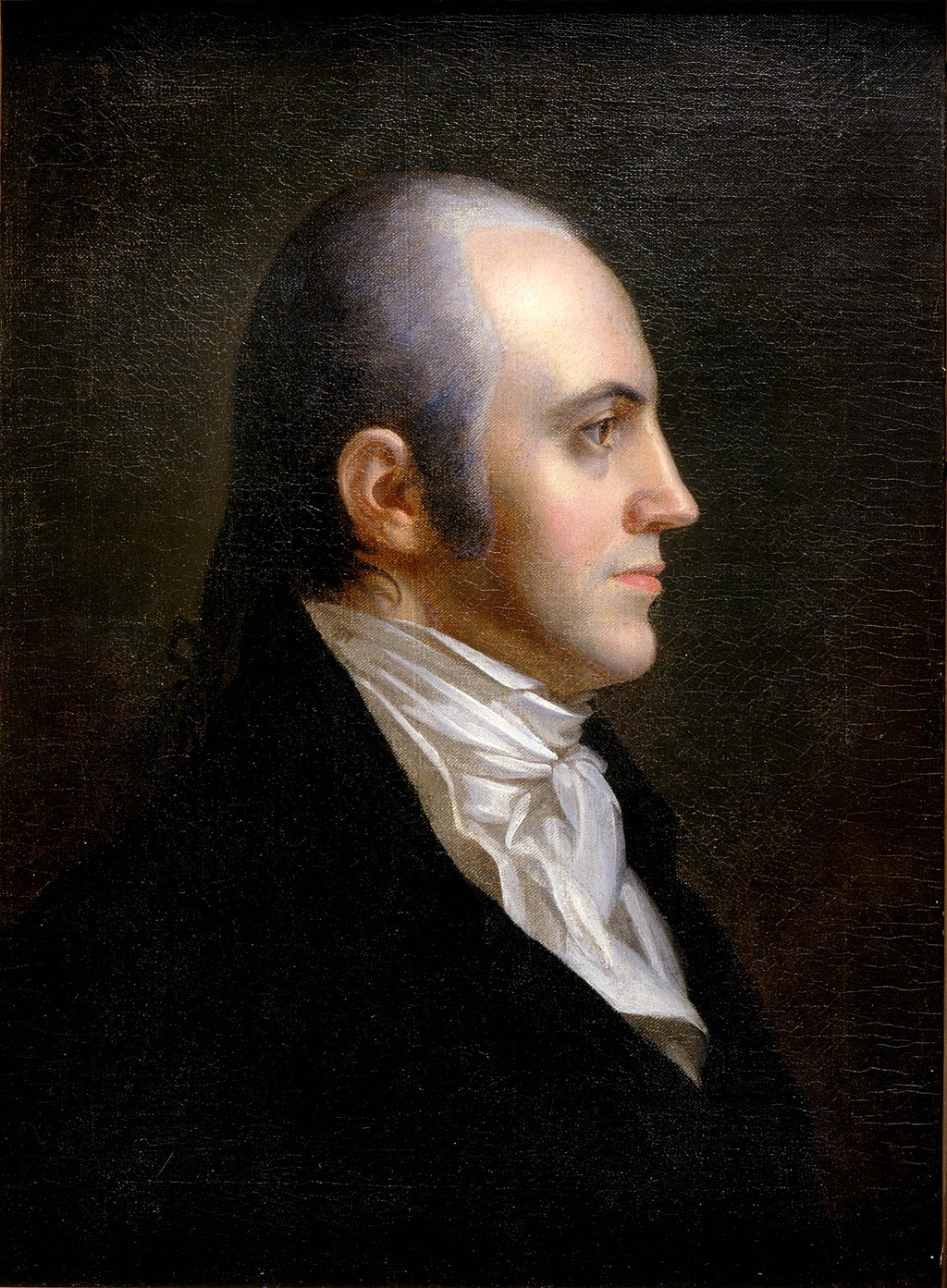

An image representing the American Know Nothing Movement. 1850s.

In 1958 for three-bits you were able to purchase "Masters of Deceit" by J. Edgar Hoover, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The book is currently available at various booksellers and online. In explaining Communist Discipline, he wrote, "Modern-day communism, in all its many ramifications, simply cannot be understood without a knowledge of Communist Discipline: how it is engendered, how it operates, how it tears out man's soul and makes him a tool of the Party.”[i]After defeating the Axis powers in the catastrophic war, a new/old threat emerged, Red Communism. The era of bomb shelters and duck and cover, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, McCarthy and Nixon, and Alger Hiss and the Pumpkin Papers. Korea ended in a stalemate, and something was brewing with the French in Indo-China. Americans were afraid.

According to J. Edgar Hoover, this was the threat America faced, "To make the United States a communist nation is the ambition of every Party member, regardless of position or rank. He constantly works to make this dream a reality, to steal your rights, liberties, and property. Even though he lives in the United States, he is a supporter of a foreign power, espousing an alien line of thought. He is a conspirator against his country."[ii]

Many questions surround the legitimacy of the 2016 elections and the current political climate in America. Regardless, we are still a scared nation, whether it be from a terrorist attack, a mass shooting, or just everyday life in poverty-stricken America. When we vote, that fear is present. We elect leaders whom we believe will take care of us. In the television show The West Wing, the character of Josh Lyman explains to an aide how the electorate makes their choice at the polls: “When voters want a national daddy, someone to be tough and strong and defend the country, they vote Republican. When they want a mommy, someone to give them jobs, health care the policy equivalent of matzah ball soup, they vote Democratic.”[iii] Researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst studied the impact of fear and anger in political information processing.[iv] They found “feelings of anger may promote voting for candidates who are well recognized, regardless of their beliefs on issues. However, fear may encourage individuals to vote for candidates whose positions on specific issues are congruent with their own, thus leading to more thoughtful, meaningful, and self-relevant choices.”[v]

At the height of the 2016 election cycle, Time magazine’s political correspondent, Molly Ball, published an article in The Atlantic. The title of her article: “Donald Trump and the Politics of Fear.”[vi] In it, she wrote: Fear and anger are often cited in tandem as the sources of Trump's particular political appeal, so frequently paired that they become a refrain: fear-and-anger, anger-and-fear. But fear is not the same as anger; it is a unique political force. Its ebbs and flows through American political history have pulled on elections, reordering and destabilizing the electoral landscape.”[vii]

It is with that premise in mind that I plan to write on the use of fear in politics, in particular, the “fear of the other.” The other being whomever the politicians need to target to arouse fear and anger. I will work through this examination in chronological order; examining various political campaigns, parties, and movements for their use of fear and treatment of the other. I will demonstrate how the use of fear impacts the electorate.

The First Immigration Crisis: The Irish and Emergence of the Know-Nothing Party

Most Americans recognize the words of the Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." Patriarchal language aside, this was a fundamental tenet of the Founding Fathers. In contrast, thirteen years later, these same founders indicated that an African-American was 3/5th a person, for purposes of the decennial census.

This American Narrative, a nation founded on the principles of freedom and equality, was accepted as truth. The narrative makes false assumptions, using an English and Protestant-centric view. The everyday use of the English language as an amalgamating societal force aided the growth of the narrative. Enacting its first Naturalization Act in 1790, the United States accepted any white person into its citizenry. Estimates are that between 1790 and 1805 immigration to the United States averaged 6,000 new citizens a year. The Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 tampered down new influxes of Americans. The first rise in immigration began in 1815, leading the Congress to enact the Steerage Act, in 1819, requiring all ships to keep detailed records of passengers and offer better transportation conditions.[viii]

Immigration to America peaked in 1854 at 428,000, with Irish and Germans escaping adverse agricultural conditions. [ix] For these immigrants, their first views of America were the port cities they disembarked from. The first test of the American Narrative began in that time and place. "In the communities where the new Irish Catholic immigrants settled, many wondered whether their presence would affect American cultural identity. Natives also expressed fears and doubts regarding the allegiance of this group to American democratic values and institutions. Finally, they feared that these newcomers were being manipulated by corrupt city politicians, who were more concerned about votes than inculcating the principles of democracy in the new immigrants." [x]

The Order of United Americans/Know-Nothing Party

Thomas R. Whitney, son of a New York silversmith, is a little-known name to most Americans. A politician and a journalist, Whitney was a moving force in the Order of United Americans (OUA), a nativist fraternity. Founded in 1846, the OUA, was an amalgam of former Whigs, Free-soilers, and nativists who opposed slavery and were concerned with the growing power of the foreign-born. Initially, a secret society (members were instructed to answer that they knew nothing about the organization if questioned), by the early 1850s knowledge of them was common. Whitney served as editor starting in 1851 of the Republic, “a monthly magazine of American Literature, Politics, and Art that the rapidly expanding OUA initiated, sponsored, and distributed. Whitney's standing in the OUA was confirmed in 1853 when he began a second term as grand sachem. In 1856 Whitney crowned his writing career with the publication of a nearly four-hundred-page Know-Nothing bible, A Defence of the American Policy." [xi]

Economic development, a homogeneous national culture, active government, and opposition to the burgeoning women's rights movement was at the heart of OUA beliefs. The nuclear family was essential and required female and filial subordination. An active government was committed to economic and cultural development. It did not offer legislation attacking societal inequality. Whitney opposed maximum hours laws, public aid to the elderly, as well as a homestead bill that proposed to grant federal lands to those without. "Government’s proper task, Whitney argued, was to shore up the foundations of existing society, serve its needs, and advance its general interests."[xii]

To Whitney and the rest of the OUA, foreign-born nationals were not reliable conservatives and would not support the American Narrative. The OUA was threatened by the new peasants, craft workers, and unskilled laborers emigrating to the United States. They did not have the proper political experience. They had the wrong acculturation. The threat to the United States came in two forms: Roman Catholics and Radicals.

IRISH NEED NOT APPLY

According to the Library of Congress, nearing one-third of those immigrating to the United States between 1830 and 1860 were Irish Catholics.[xiii]

An Anti-Catholic fervor swept the nation. One conspiracy theory postulated the Catholic Church was behind the influx of Irish. The Irish also represented a greater fear for the OUA; they did not own property, so they were corruptible, irresponsible, and ignorant. The OUA used propaganda that the Irish were uneducated, politically unaware and easy to manipulate to attract men (i.e.voters) to the OUA. Voters were scared that the corruptible immigrants would prevent "good men" from governing. [xiv]

There was also a fear of radicalism, as Europe was undergoing its transformation in the 1840s. A riot between striking Irish dock workers and strikebreakers exemplified this radicalism. The political upheaval of 1848 added to the fear of newly arrived citizens. Some of the radical ideas were coming out of Germany; thus German emigres were marked as targets. In speaking of these working-class immigrants, Whitney said they were "carriers of a deadly plague--Red Republicanism." [xv]

The political wing of the OUA, the American Party, had strong showings in the elections of 1852 and 1854. The American Party drew most of its support from New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. The 1855 Congressional session started with 43 members of the American Party. Their candidate for President in 1856 won 21% of the vote.[xvi]

The leaders of the American Party were men who had never voted and defectors of the Whig Party. They promised to take power away from the political machines, to "drain the swamp," as it were. They proposed a direct primary voting system and required candidates for office to be "fresh from the people-not professional, no politicians." As a result, most, American Party candidates were inexperienced and incompetent.[xvii]

America, then as in now, was a nation in crises. The people, the voters, were scared. There were more Irish, Germans, and other Europeans coming to America. The revolts in Europe in 1848 added to the influx. The uneducated immigrants added to the population of the emerging cities. Soon, ghettos would appear. As the towns grew so did their political machines. These events added up to a threat against the traditional American narrative cherished by Thomas Whitney and others like him. They seized upon the inherent fear of the other in trying to preserve the American Narrative, never knowing they were altering it by their use of fear.

To be continued.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

You can read more of Jonathan’s work at Portable Historian: www.portablehistorian.com.

[i] J. Edgar Hoover, Masters of Deceit, (NY, 1958), 163

[ii] Ibid., 4

[iii] Elie Attie, “The Mommy Problem,” The West Wing, (2005) https://www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk/view_episode_scripts.php?tv-show=the-west-wing&episode=s07e02

[iv] Michael T. Parker and Linda M. Isbell, “How I Vote Depends on How I Feel: The Differential Impact of Anger and Fear on Political Information Processing,” Psychological Science, 21 (April 2010), 548.

[v] Ibid., 549

[vi] Molly Ball, “Donald Trump and the Politics of Fear,” The Atlantic, September 2, 2016, 1.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] The Statute of Liberty- Elis Island, "Immigration Timeline," https://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/immigration-timeline#1790

[ix] Raymond L. Cohn, "Nativism and the End of the Mass Migration of the 1840s and 1850s," The Journal of Economic History, 60 (June 01), 361.

[x] Jose E. Vega, "Cultural Pluralism and American Identity: A Response to Foner's Freedom and Hakim's Heroes," OAH Magazine of History, 20 (July 2006), 19.

[xi] Bruce Levine, "Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-Nothing Party," The Journal of American History, (Sept 2001), 461-463.

[xii] Ibid. 464-466

[xiii] https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/irish2.html

[xiv] Levine, 468

[xv] Ibid., 469

[xvi] Encyclopedia Britannica, "Know-Nothing Party," https://www.britannica.com/topic/Know-Nothing-party; Michael F. Hot, "The Politics of Impatience: The Origins of Know-Nothingism," The Journal of American History, 60 (September 1973) 311.

[xvii] Ibid., 311, 318,319