Funerals and burials are a hugely important part of modern British life. Although we thankfully now live longer and fuller lives than our ancestors, the loss of a loved one is no less heartbreaking. How we mourn and grieve in the immediate aftermath of a death remains a central part of how we move on with our lives, from one generation to the next.

We’ve come a long way in the UK in terms of funeral traditions. From the pre-Christian Celts who believed in reincarnation filling their graves with items needed for the next life, to our modern day scientific knowledge of the process of death. Yet some customs and traditions have remained through the ages.

Here, Laura Fulton explores some of the key aspects of modern UK funerals, where they come from and how they’ve changed over time.

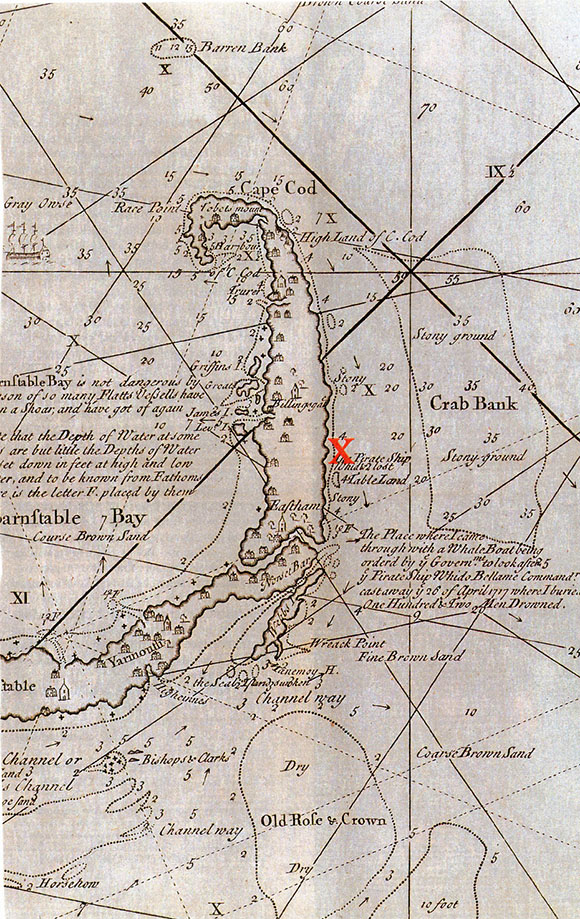

A 15th-century funeral at Old St. Paul's Cathedral in London, UK.

Obituary notice

In the UK it is traditional for families to announce a death to the community by way of a death notice usually published in the local paper, and including details of the funeral.

Coming from the Latin obit meaning “death”, published death announcements date back as early as the 16th century in America. But it would be 300 years before the British made longer obituaries standard. There was even a time in the early 1800s when it was popular to write them in poetic verse. They were usually reserved for people of social prominence, such as soldiers or public servants. However the 20th century saw the rise of the “common man” obituary when the deaths and funeral details of everyone in the community would be regularly published, giving them equal status - in death at least - as members of the local aristocracy.

In modern Britain, we now see social media networks such as Facebook giving the option for a named person to take control of your profile after death, turning it into a public memorial place to list funeral details and accept messages from friends and well-wishers.

Black clothing

The tradition of wearing black in mourning dates back to Elizabethan times and it remains in the UK to this day, albeit in a more relaxed fashion. The ritual reached its peak in Victorian times during the Queen’s prolonged mourning for Prince Albert when widows became expected to wear full mourning attire for two years.

Funeral attendees now wear a mixture of dark colors from black, to navy and brown, but not exclusively. It is increasingly common for mourners to be asked to wear a specific color, such as a favorite sports theme or a young child’s favorite color, to celebrate their life at the ceremony.

Mourning rings were another important part of Shakespearean funeral dress but the tradition has largely died out. The rings were made to memorialize death, often featuring skulls, coffins, or crosses.

Funeral procession

Funeral processions led by the hearse (funeral car carrying the coffin) are still used in UK funerals, particularly in close-knit communities. There are actually no motoring laws surrounding this aspect of a funeral, but even though the days of horse and cart corteges have gone, modern passers-by still recognize the procession and will often be seen to stop and pay their respects before moving on.

Funeral processions date back to ancient times around the world. Though considered a distinctly Roman tradition in ancient Britain, the introduction of the word funeral itself into public discourse is credited to acclaimed ‘Father of English Poetry” Geoffrey Chaucer in the 1300s. The word appears in The Knight’s Tale (the first of The Canterbury Tales), where he talks about the sacred flames from a funeral pyre rising. It originates from the Medieval Latin funeralia meaning “funeral rites.”

Funeral processions in Roman times looked very different, and sounded different too. Professional mourners were paid to form part of the funeral procession, wailing loudly. The larger the procession, the more noise and music, the wealthier and more powerful the deceased person was regarded to be.

Wake

Wakes remain a modern day practice in UK funerals. The wake is often now held after the burial service, in either an immediate family member’s home or a local hospitality establishment. The sentiment behind it is to take time to share memories, to celebrate their life, and to grieve together.

The practice originates back to ancient Anglo-Saxon times when Christians held celebrations (wakes) which involved sports, feasts and dancing. Through the night there would be prayer and meditation in church, followed by a day of recognized holiday in the parish.

However the tradition of the wake dates back even further - long before Christianity. It referred to the period of time before burial, when family and friends would keep a constant vigil over the body as it lay in wait at the home. This gave time for mourners to travel from further away, but also had its roots in superstition. A vigil meant that the body had to be kept safe from ancient dangers such as body snatchers or evil spirits. The night-long activity was then known as “waking the corpse.”

Chapel of rest

The funeral director’s private viewing area or “chapel of rest” remains an option in UK burials for those who don’t want to or can’t permit the body to be brought to the home before the funeral. It was a late Victorian development as attitudes to hygiene and superstition changed and people began to feel more comfortable allowing mourners to visit the dead at a place separate from where they would continue to live.

Funeral flowers

Flowers were traditionally used alongside candles in the room during wakes to mask unpleasant smells which we have now avoided thanks to advances in mortuary care; however the deeper meanings behind the tradition have encouraged its continuation. White lilies remain the most popular flower choice, stemming from their symbolism of the innocence of the soul.

More commonly now, flowers from mourners are viewed as a poor use of money and so instead, the family and friends will ask for donations in lieu of flowers. Sometimes by a donation to a charity close to the deceased person’s heart, or often an organization or cause linked to their death, for example a palliative care or hospice service.

This is actually a long-standing tradition from Elizabethan times, when money would be given to the poor as part of the feast of mourning.

Burial

In most Christian cemeteries, the majority of traditional graves will be found facing west to east (head to feet). This old custom originates back to the sun worshippers of Pagan times, however early Christians adopted it because they believed this allowed the dead to be facing Christ on the day of Resurrection. In ancient Celtic times, the burning of loved ones was more common.

Nowadays, burial and cremation are equally an option, especially since the Church announced that ashes could be held on sacred ground. Mourners will still often throw soil, flowers or personal items on top of a lowered coffin, a tradition dating back centuries.

Gravestones as markers of burial are a UK tradition that dates right back to circa 2,000 BC in the UK, with Stonehenge being one of the most renowned ancient gravesites in the world. Through the plague decades burials were moved to designate sites outside towns, with the poor using wooden crosses instead of stone. But again, the tradition of carved headstones dates back to Victorian times.

Mementos

Victorian burials in the UK included some now-considered macabre ways of remembering lost loved ones, from post-mortem photography to the weaving of their hair onto jewelry and ornaments.

However, the idea behind this old tradition is making somewhat of a comeback, with companies now offering the service of turning the ashes of a loved one into a diamond for example.

Forgotten Superstitions

Elements of UK funerals that have definitely gone out of favor are the once-important superstitious customs. These included stopping the clocks in the room the person died in to prevent bad luck, covering mirrors so their soul wouldn’t get trapped in the glass, and turning family photographs face-down so that the people in them would not be possessed by the spirit of the dead.

New trend: a celebration of life

In the 1800s it was customary to hold a celebratory feast in honor of the deceased person after their burial. This continued into the 1900s and only dipped in favor a little through the War periods. The celebratory post-funeral pub gathering remains popular in parts of the UK but increasingly, among younger generations, is a growing trend for “happy funerals” too.

Upbeat songs during services through to ashes being spread via fireworks are no longer unheard of.

The future: green goodbyes

The growing concerns about the environment and global warming have led to modern legislation around how and where we bury or cremate bodies. But increasingly people are being more proactive on this, planning for their own “green” burials.

Disposable coffins have emerged, alongside the growth of woodland burials and memorial trees planted in place of traditional headstones. There are even virtual memorial gardens online displaying people’s life stories.

So funerals are moving away from a focus on the processing of the body, with strict guidelines on behavior, dress and ritual to a more informal style of gathering and grieving among surviving relatives and friends. Instead of focusing on the sadness of death, we see society move towards funerals that are a celebration of life.

The growing trend to blend traditional customs with new and celebratory elements is resulting in a more personalized goodbye that our loved ones who have left us, can be proud of.

How do funeral traditions vary in your country? Let us know below…

Finally, Laura has asked us to mention 360 Protection Choices Life Insurance.