Throughout the history of foreign policy, arguments have been made that public opinion is ineffective and cannot influence foreign policy, with cogent arguments being made by respected writers, historians, and international relations theorists likeWalter Lippmann, Thomas A. Bailey, and George F. Kennan. However, public opinion can influence foreign policy to a large degree.

Here, Alan Cunningham explains how US military conflicts have been influenced by public opinion.

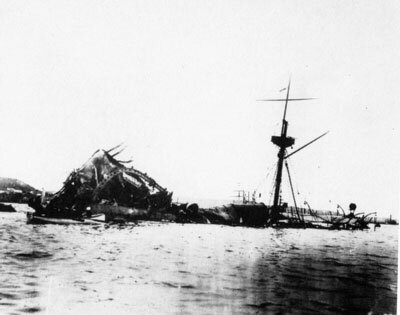

The sunken USS Maine in Havana harbor, leading to the 1898 Spanish-American War.

By simply looking at military conflicts in the United States, we can find that many of these are sharply influenced by U.S. public opinion. The American Revolution, the First World War, the Second World War, the Vietnam War, and the 2003 Iraq War were all heavily influenced by the public’s desires and the media. Individual operations, such as 1989’s Invasion of Panama, 1916’s Pancho Villa Expedition, and 1980’s Operation Eagle Claw, too suffer from public opinion; if the public and Americans’ at large feel that the operation or the conflict is worthwhile, assists in preserving American security and safety, or stops an extreme crisis (like genocide or crimes against humanity) then the overall foreign policy goal continues, but that public support is integral.

Ole Holsti, a professor of political science at Duke University, writes, “the Vietnam War served as a catalyst for a re-examination of the post-World War II consensus on the nature and effects of public opinion. Although these recent studies continued to show that the public is often poorly informed about international affairs, the evidence nevertheless challenged the thesis that public opinion on foreign policy issues is...without significant impact on policy making”. I agree that while most of the public is largely uninformed on international issues and key political-military affairs (social media posts about a draft for World War III in the aftermath of General Qasem Solemani’s targeted killing exemplifies this in my view), the public’s voice does matter and can significantly shape foreign policy decisions and what actions a state takes. The 1993 Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia and the 1898 Spanish-American War are prime examples of this.

1993 Battle of Mogadishu

To first understand the battle, one must look back at the conditions that shaped Somalia into needing outside, global intervention. The country had long been ruled by Mohamed Siad Barre, a ruler who had accepted both U.S. and Soviet aid, and eventually lost hold of his nation due to declining influence, the collapse of the Soviet Union and a major benefactor, and poor economic policies thrusting the country into decline; In 1991, a rebellion overthrew Barre which resulted in a civil warbased upon tribal lines. The UN developed a task force to return order to the country and U.S. Marines invaded and removed the major tribal forces from power in the capital of Mogadishu. Upon completion of the humanitarian mission, however, it became apparent that the strongest warlord, Mohammed Farrah Aidid, would return to power, so the U.S. began planning to return Somalia to a democracy. As most know, the following six weeks of military special operations were successful, but eventually made large scale, international news when Special Operations Forces operators became entrenched in a fifteen-hour firefight defending two crashed helicopters, with nineteen U.S. military personnel and two UN multinational force soldiers being killed throughout the entirety of the mission. While the mission itself (to capture two high level members of Aidid’s clan) was a success and the U.S. military severely crippled the clan’s military capacity, public opinion about the conflict was molded heavily after seeing the bodies of U.S. servicemen being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. Pressured by their constituents, Congress began making similar statements and eventually the Clinton administration decided to fully remove American forces from Somalia.

Public opinion in this case completely changed the outcome of the entire, two-year mission in Somalia and essentially dictated Bill Clinton’s foreign policy until 1995. Due to the public’s desire to focus on domestic issues and not become embroiled in a foreign war (especially one that many saw as having no clear exit strategy or goals), Clinton’s administration kept out of Darfur, Rwanda, and (at least initially) Bosnia. Public opinion dictated how the U.S. should respond in these incidences and eventually forced the administration to reintegrate themselves into defending against genocides after the Rwandan incident.

1898 Spanish-American War

Another example of this can be seen with the Spanish-American War. The Spanish Empire was largely seen as a nuisance and fear to the U.S., being an imperial force so ingrained and entrenched within the Western Hemisphere. Being that the Cuban Revolution was largely seen as a force for democracy and were portrayed as brothers to the American public, many imperialists began calling for war against the Spanish. This call was bolstered by Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal and eventually culminated with the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor; with news reports claiming that the Spanish had deliberately sunk the warship, the U.S. made preparations for invasion and launched operations. While the war was short and something of an anomaly in military endeavors (with more personnel dying due to diseases than bullets or wounds), the impact of this was that Cuba’s populace were freed and then immediately put under U.S. rule for a period of time before being handed over to pro-U.S., anti-Communist strongmen like Fulgencio Batista. What this points to is the effect that public opinion and desires have upon foreign policy decisions. While some blame solely Hearst and Pulitzer for beginning the war and single-handedly provoking war, it is important to note that both Pulitzer and Hearst did not have an audience outside of New York and only appealed to the working class, not anyone in politics or white collar workers. As Thomas Kane points out in the journal Contemporary Security Studies, the true decision to invade was because the broad majority of Americans were sick of bloodshed and because many in American politics agreed that trying to contain the situation in Cuba was lost. In the end, public opinion mattered, not how influential newspapermen were.

Conclusion

In both of these, public opinion and support or opposition towards specific policies played a large role in determining how the government would deal with foreign policy matters and how individual administrations would deal with future crises in the globe. Public opinion and outward support of operations, military conflicts, or foreign policy goals has enough coherence to be effective and to seriously change the way that governments operate and go about performing missions and attaining their overall goals.

What do you think of the role of public opinion in influencing foreign policy in the US? Let us know below.

About

Alan Cunningham is a graduate student at Norwich University where he is pursuing an MA in International Relations. He will be joining the United States Armed Forces upon the completion of his degree and aims to gain a PhD in History and a JD from Syracuse University. He has been published in the Jurist, Small Wars Journal, the U.S. Army War College’s War Room, and Eunomia Journal.