Major General George McClellan was one of the central figures of the Civil War. He served as commander of the Department of Ohio, the Army of the Potomac, and was Commander-in-Chief of the Union Army for 5 months. Historically, his command decisions have been criticized and his personal qualities are examined minutely. He represents a paradox: a superbly prepared and highly intelligent man who, during his moment on the world stage, failed in almost every task he performed.

Lloyd W Klein explains.

George B. McClellan. Portrait by Mathew Brady.

Background

McClellan came from a wealthy, elite Philadelphia family. His father was Dr George McClellan, a foremost surgeon of his day and the founder of Jefferson Medical College. A great grandfather was a brigadier general in the Revolutionary War. After attending the University of Pennsylvania for two years, he left to enroll at West Point, where he graduated second in his class at age 19 in 1846, losing the top spot because of weaker drawing skills. He was friends with aristocratic southerners including George Pickett, Cadmus Wilcox and AP Hill.

He was breveted a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. During the Mexican War he served as an engineer building bridges for Winfield Scott’s army. He was frequently under fire and was breveted to first lieutenant and captain. Since his father was friends with General Scott, he received a coveted spot to perform reconnaissance for the general.

He returned to West Point as an engineering instructor after the war. He was given charge of various engineering projects. He was also sent on a secret mission to Santo Domingo by the Secretary of State to scout its military preparedness. In 1852 he helped to translate a manual on bayonet tactics from French. In 1853, he participated in land surveys to scout a transcontinental railroad route. The route he advised through the Cascade Mountains, Yakima Pass, was known to be impassable during the winter snow. The Governor of Washington territory, himself a top of the class graduate of West Point and a mathematics whiz, had made his own survey. He knew that McClellan hadn’t studied the situation carefully. Time has shown that he missed three greatly superior passes in the near vicinity, which were eventually used for railroads and interstate highways.

He was then appointed By Secretary of War Jefferson Davis as captain of the new First Cavalry Regiment, one of two that would be the proving grounds for the Civil War. Because he spoke French fluently, he was sent to be an observer during the Crimean War. There he conferred with military leaders and the royal families on both sides. He observed the siege of Sebastopol first-hand. His report was hailed for its brilliance. McClellan's observations and insights from the Crimean War played a role in shaping his views on military organization, logistics, and the importance of proper training. He was particularly impressed by the Allied forces' well-organized supply lines, medical services, and use of siege warfare. However, he totally missed the significance of how rifled weapons had changed military strategy, an error that would have substantial repercussions in the conflict ahead. McClellan wrote a cavalry manual and designed a saddle, called the McClellan saddle, which is still in use for ceremonies. This was a promising young man with a great future.

But the fact is, promotion in the small pre-war army was very slow, and McClellan was an ambitious man. At age 31, he resigned to become Chief Engineer of Illinois Central Railroad, a position with a huge increase in salary. There he would be promoted to Vice President and work with an obscure railroad lawyer named Abraham Lincoln.

McClellan was, frankly, bored with railroad management. He served as chief engineer and vice president of the Illinois Central Railroad, and then became president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad in 1860. McClellan supported the presidential campaign of Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 election. He also married Mary Ellen Marcy, a woman who had fielded 8 prior proposals, rejecting 7 of them, including a prior one from McClellan; the man she had accepted was not liked by her family, so he withdrew. Finally McClellan asked again, and they were married in New York City in May 1860.

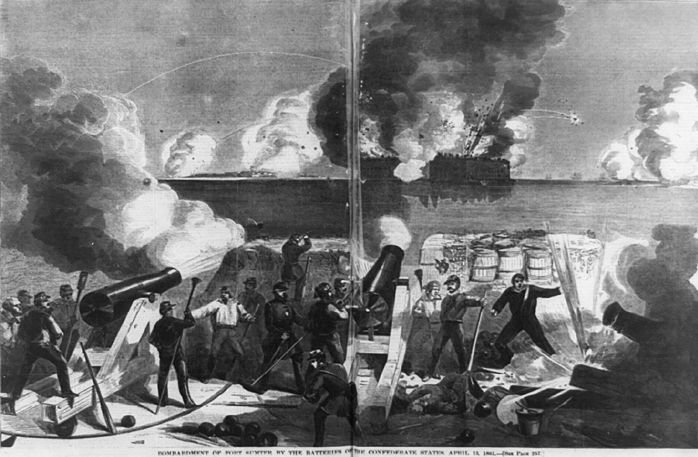

Start of the Civil War & Rapid Promotion

The firing at Fort Sumter changed the trajectory of a lot of people’s lives. For McClellan, it was transformative: he found himself a highly regarded and sought after authority on large scale war and tactics, having written two volumes on the subject. He was wanted by the Governors of 3 states to lead their militias, and he settled on Ohio. He was commissioned a major general in the regular army on Amy 14, 1861, outranking everyone except Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, the general-in-chief. McClellan's rapid promotion was partly due to his acquaintance with Salmon P. Chase, Treasury Secretary and former Ohio governor and senator. Once again, political connections moved him rapidly to the top.

After losing First Manassas, Lincoln needed a military leader who could win battles. McClellan had several victories in western Virginia including Rich Mountain and Cheat Mountain, and was being hailed as the “Young Napoleon” and “Napoleon of the Present War” in the press. But the fact is, McClellan’s actions there showed a number of disturbing features that in retrospect were prescient. McClellan failed to attack at Cheat Mountain several times despite action being underway. Colonel Rosecrans was promised reinforcements but McClellan didn’t send them, forcing him to achieve victory on his own; McClellan’s report gave him no credit. Another subordinate was warned to follow cautiously but then criticized in the report for moving slowly.

Positive Attributes

There can be no doubt that he was a fabulous administrator and logistician. He excelled in organizing and training the Union Army at the start of the war, preparing them for the battles ahead. His meticulous attention to detail and emphasis on discipline contributed to a well-structured and efficient force. Additionally, he implemented effective supply and transportation systems to support his troops. His skills in these administrative tasks were superb and are appropriately admired by all.

Criticisms as Commander in Chief

Throughout his tenure as a commander, McClellan consistently exhibited a tendency to overestimate the strength of his opponents and to be overly cautious in his decision-making, often erring on the side of preserving his own forces rather than aggressively engaging the enemy. McClellan was reluctant to begin his offensives, routinely delayed attacking, demanded an impossible number of reinforcements even though his army greatly outnumbered the enemy, displayed insubordination to the President and civilian leaders, allowed the enemy to escape repeatedly, and retreated several times despite not having lost a battle. He had an inability to create original or innovative ideas, despite being tremendously smart and a quick study. His cautious approach to battle and reluctance to take decisive offensive actions limited his overall success as a military leader.

Over-Cautiousness

Several instances highlight McClellan's consistent pattern of over-cautiousness, which led to missed opportunities and strategic setbacks:

Peninsula Campaign: McClellan's Peninsula Campaign was marked by his excessive caution. Despite having a numerical advantage over Confederate General Robert E. Lee, McClellan moved slowly and hesitated to press his advantage, allowing Lee to consolidate his forces and ultimately repel McClellan's advances.

Seven Days' Battles: During the Seven Days' Battles, McClellan's caution led him to withdraw his forces in the face of Lee's attacks, despite having numerical superiority. This retreat allowed Lee to successfully defend Richmond and avoid being decisively defeated.

Maryland Campaign: After discovering Special Order #191, McClellan has been criticized traditionally as moving slowly. Even though McClellan had gained intelligence indicating that Lee's forces were divided, he still proceeded cautiously. However, recent scholarship has questioned the accuracy of this conclusion.

Battle of Antietam: This battle became the single bloodiest day in American history, and McClellan's failure to exploit his opportunities to defeat Lee's army decisively was attributed to his caution.

Following the Battle of Antietam, McClellan was slow to pursue Lee's retreating army, allowing them to escape across the Potomac River into Confederate territory. His hesitation to pursue and engage the enemy hindered the Union's success in taking advantage of its tactical success.

Repeated Inflated Estimates of Enemy Strength

McClellan’s propensity to inflate enemy troop numbers occurred so routinely that it’s beyond possibility that it wasn’t intentional, and perhaps psychologically motivated.

The pattern of inflating enemy troop numbers was a recurring theme that marked McClellan's career. McClellan doubled the number of troops he had defeated at Rich Mountain, making his victory appear spectacular. He tripled the number of actual troops facing him across the Potomac, leading to a crisis sense and elevation to commander in chief. In the Peninsula Campaign, the process reached its zenith: hyper-inflate the numbers of the enemy, lament about what was necessary to win, when it was impossible to provide that number to reluctantly proceed anyway, and blame superiors if victory wasn’t achieved.

Procrastination

McClellan’s fatal flaw as general was that he was viewed as a procrastinator. His continual delays and refusal to move against the Confederates allowed them to call in reinforcements and win key battles with less than half the manpower. McClellan had a long history of delaying attacks. Maybe he thought that he had to plan in great detail before launching them. But these delays were never beneficial and never justifiable. His delay to initiate the battle at Antietam cost him a decisive victory and ultimately led to his dismissal.

He was an excellent administrative general, but as a tactician he was incapable of taking chances, and war is all about chances. Strategically he really wasn’t bad: Peninsula was an interesting idea but he did not follow through tactically. He wanted to cross the James, as Grant would do 2 years later, but was denied. He had a great advantage at Antietam and won, but he failed to pursue the enemy. He might have been incapable of responding creatively to the real time exigencies of battle. He could not creatively adjust his plan. Thus, at Antietam, when his plan of assault did not unfold like a predetermined Napoleonic success, he was unable to develop any new concepts on the spot to adapt to the changed circumstances.

It is also possible that there were cynical benefits to General McClellan's exaggerated reports of the enemy's size. By consistently overestimating the enemy's strength, McClellan could have positioned himself as the savior of the Union, creating a narrative that he was the only one capable of defending against such a formidable foe. This could have enhanced his political stature and potentially garnered more support from certain factions. McClellan's tendency to exaggerate the enemy's strength could have provided him with a convenient excuse for his reluctance to engage in battle or take more aggressive actions. This allowed him to avoid the risks associated with decisive battles, while placing the blame on the perceived overwhelming enemy forces .And, by portraying the enemy as stronger than they actually were, McClellan might have been able to secure additional resources, troops, and supplies for his own forces. This could have allowed him to build up a larger and more well-equipped army, potentially boosting his own reputation in the process. Finally, the exaggerated reports could have been a way for McClellan to deflect blame for any failures or setbacks onto the supposedly formidable enemy forces. By doing so, he could have avoided taking responsibility for any missteps in his own strategy or decision-making.

Psychological Profile

Psychological profiling of historical figure is fraught with hazard. Nevertheless, historians have found McClellan to be an excellent subject for this kind of analysis. McClellan has been portrayed as “… proud, sensitive, overwrought, tentative, quick to exult and to despair”. He was a competent administrator and engineer who had no skill at winning battles. McClellan's actions and exaggerations might have been influenced not only by strategic considerations but also by his own ambitions and self-preservation. His reluctance to engage in battle can be attributed in part to his fear of failure. His job was to lead, he was supposed to be a great leader, but he was afraid to be wrong. McClellan was more concerned with not losing than with winning. In his mind, as the fate of the Union rested on his shoulders, he could not allow a defeat.

Stephen Sears wrote: “There is indeed ample evidence that the terrible stresses of commanding men in battle, especially the beloved men of his beloved Army of the Potomac, left his moral courage in tatters. Under the pressure of his ultimate soldier's responsibility, the will to command deserted him. Glendale and Malvern Hill found him at the peak of his anguish during the Seven Days, and he fled those fields to escape the responsibility. At Antietam, where there was nowhere for him to flee to, he fell into a paralysis of indecision.”

A fragile ego covered by conceit was reflected in many of his letters to his wife.

He had to build himself up because in fact he lacked self-confidence. McClellan often suggested that divine intervention had chosen him to save the Union. McClellan frequently thanked God for allowing him to be the deliverer of the nation. His letters to Ellen Marcy, his wife, have been widely quoted in this regard (see Table). Many of the letters were intentionally destroyed or burned in a fire after the war, and there is a great deal of speculation as to exactly why the ones that remained still exist. Allan Nevins wrote, "Students of history must always be grateful McClellan so frankly exposed his own weaknesses” in his memoirs.

************************************************************************

Some well-known quotes from his letters to his wife:

“I find myself in a new and strange position here: President, cabinet, Gen. Scott, and all deferring to me. By some strange operation of magic I seem to have become the power of the land … I almost think that were I to win some small success now I could become Dictator. . . . But nothing of that kind would please me. Therefore I won't be Dictator. Admirable self denial!”

“Half a dozen of the oldest made the remark . . . ‘Why how young you look — yet an old soldier!! ... It seems to strike everybody that I am very young. . . . Who would have thought when we were married that I should so soon be called upon to save my country?”

“The President is no more than a well-meaning baboon. I went to the White House directly after tea, where I found "The Original Gorilla", about as intelligent as ever. What a specimen to be at the head of our affairs now.”

““It may be that at some distant day I too shall totter away from” Washington, “a worn out old soldier. . . . Should I ever become vainglorious & ambitious remind me of that spectacle.”

“I ought to take good care of these men. I believe they love me from the bottom of their hearts. I can see it in their faces when I pass among them.”

************************************************************************

Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote that a review of his personal correspondence during the war, especially with his wife, reveals “a tendency for self-aggrandizement and unwarranted self-congratulation.” McClellan thought of himself as the only man who could save the union, and was willing to sacrifice anything and anyone—mentors, colleagues, his own men—to further his ambition. In that sense, George McClellan's memoirs and letters provide some indications of his personality and mindset, and a narcissistic tendency is suggested. But drawing definitive conclusions about his psychological condition, such as labeling him as a narcissist, solely based on these sources can be misleading.

In contradistinction, Lincoln had failed in life before; he made himself a success by hard work and careful thought, and wasn’t afraid of risk. McClellan had been handed everything, had always come out on top, and was afraid to fail. In war, as in much of life, fortune favors the bold. McClellan’s fear of failure and routine promotions on the basis of political connections would be his downfall.

Relationship with President Lincoln

The personal and professional conflict between General McClellan and President Lincoln that manifest in 1862, and continued into the election of 1864, is one of the fascinating subthemes of Lincoln’s presidency. Lincoln and General McClellan didn’t like one another and didn’t get along well. McClellan believed he had a superior education and family background; Lincoln knew he was being looked down upon, but with his superior emotional quotient, he knew that what was important was getting victories, and if this man could, then he would put up with him.

They originally met before the war: Lincoln was an attorney for the Illinois railroad and the two spent time together between cases. He saw Lincoln as socially inferior and intellectually not nearly on his level. He found the country stories Lincoln told to be below him.

Once the war began, Abraham Lincoln and George B. McClellan clashed repeatedly. McClellan constantly ignored Lincoln’s orders, and did not share his plans with anyone including the president. McClellan let it be known that he had contempt for Lincoln. He called him the ‘original gorilla’ in public. On November 13, 1861, Lincoln Seward and Hay stopped at McClellan’s home to visit with him. McClellan was out, so the trio waited for his return. After an hour, McClellan came in and was told by a porter that the guests were waiting. McClellan headed for his room without a word, and only after Lincoln waited another half-hour was the group informed of McClellan’s retirement to bed.

Historian William C. Davis wrote that in 1861, “believing what the press and an admiring circle of sycophants on his staff and high command said about him, Little Mac bristled at being subordinate to the civil authority, and especially to Lincoln, of whom he almost instantly developed a condescending and patronizing opinion. He not only regarded the president as his intellectual and social inferior, but also passed on that attitude to those around him – or even fostered it.”

Famously, President Lincoln came to visit General McClellan on October 3rd. As you can see from the photo by Alexander Gardner, the temperature of the meeting was frosty. Abraham Lincoln spent four days travelling over the field, just two weeks after the guns fell silent. He met with McClellan, trying to prod his young Napoleon into action, met with other generals, and with thousands of wounded soldiers, Including both Union and Confederate. His trip was well-documented, and the photos of his visit are among the most famous of the entire war.

Lincoln expected McClellan to pursue Lee and engage him in a decisive battle as soon as possible. Although the Union outnumbered the Confederate army by almost three to one, McClellan did not move his army for over a month. McClellan overestimated the size of Lee’s force, suggesting that 100,000 troops were in his command, when he likely had just more than half that number. McClellan also noted that his requisitions for supplies had not been filled. Although traditionally these complaints are dismissed as a manufactured excuse, substantial documentation suggests that McClellan had a genuine supply crisis.

It may be that top Lincoln administration officials ruined his reputation intentionally for political reasons. Knowing that he was popular with the troops and a Democrat, they could see where 1864 was leading. That is not to say that McClellan wasn’t slow at times, but it may have been exaggerated in retrospect when he became Lincoln’s opponent.

What were McClellan’s political opinions about slavery, defeating the South, and his post bellum vision?

McClellan’s view on how the war should be prosecuted differed significantly from Mr. Lincoln’s views. McClellan was a Democrat. He was anti-emancipation. He made clear also his opposition to abolition or seizure of slaves as a war tactic, which put him at odds with the executive branch and some of his subordinates. He had a set of political beliefs almost completely at odds with the Republican Party, the party in power. Most of the officers in the United States Army were Democrats. The army was a conservative institution and many of these officers didn’t agree with the vision for the United States that many of the Republicans had, especially the radical Republicans in Congress, who even departed more radically from Lincoln.

What McClellan wanted to do was to restore the Union to what it had been. He was very happy with that Union. And that was not going to be possible during the war once it had gone past a certain point. McClellan was very clear about what kind of war he wanted. He wanted to beat the Rebels just enough to persuade them to come back under the Union. He didn’t want to slaughter their armies. He didn’t want to overturn their civilization, and he wanted to keep emancipation out of the picture.

McClellan had different views about race and southern aristocracy then we do today and that Lincoln had then: but he was not a traitor, and he did want to win the war, not lose it. McClellan emphasized the fact that he previously led the Union military effort in the War and that he was and remained committed to "the restoration of the Union in all its integrity" and that the massive sacrifices that the Union endured should not be in vain.

As he wrote to one influential Northern Democratic friend, and I’m quoting him here, “Help me to dodge the n____. I’m fighting to preserve the integrity of the Union.” That’s McClellan’s take on the war. He was not fighting to free the slaves, and he was not alone. McClellan almost never spoke of African Americans, and when he did it was always in disparaging terms. McClellan was a quiet racist, one who wanted to ensure that the Civil War ended soon so that the question of black emancipation would not become the leading element.

Now, it must be emphasized that up to that stage of the war, Lincoln was also highlighting union and not slavery. He downplayed emancipation because he thought it would alienate the border states, and he wanted to make sure that they stayed in line. After Antietam, Lincoln thought the North was ready for emancipation, but McClellan never changed his attitude.

Quotes from President Lincoln’s Letters to General McClellan

“After you left, I ascertained that less than twenty thousand unorganized men, without a single field battery, were all you designed to be left for the defense of Washington, and Manassas Junction … My explicit order that Washington should, by the judgment of all the commanders of Army Corps, be left entirely secure, had been neglected– It was precisely this that drove me to detain McDowell– … I do not forget that I was satisfied with your arrangement to leave Banks at Mannassas Junction; but when that arrangement was broken up, and nothing was substituted for it, of course I was not satisfied…”

“There is a curious mystery about the number of the troops now with you. When I telegraphed you on the 6th saying you had over a hundred thousand with you, I had just obtained from the Secretary of War, a statement, taken as he said, from your own returns, making 108.000 then with you, and en route to you. You now say you will have but 85.000, when all en route to you shall have reached you– How can the discrepancy of 23.000 be accounted for?” (April 7, 1862)

“And, once more let me tell you, it is indispensable to you that you strike a blow– I am powerless to help this– You will do me the justice to remember that I always insisted, that going down the Bay in search of a field, instead of fighting at or near Manassas, was only shifting, and not surmounting, a difficulty — that we would find the same enemy, and the same, or equal, intrenchments, at either place– The country will not fail to note — is now noting — that the present hesitation to move upon an intrenched enemy, is but the story of Manassas repeated–“

“You remember my speaking to you of what I called your over-cautiousness. Are you not over-cautious when you assume that you can not do what the enemy is constantly doing? Should you not claim to be at least his equal in prowess, and act upon the claim?” (October 13, 1862)

“Again, one of the standard maxims of war, as you know, is “to operate upon the enemy’s communications as much as possible without exposing your own.” You seem to act as if this applies against you, but can not apply in your favor.”

“I have just read your despatch about sore tongued and fatiegued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?”

************************************************************************

The 1864 Presidential election

By the summer of 1864, the Civil War had gone on for over three years. Over 250,000 Union soldiers had been killed, with many more injured permanently. Victory was not yet in sight. Democrats knew that many of the policies of Lincoln were not popular, including many of those we take today as the reason for the conflict, such as emancipation, the military draft, the use of black troops, and violations of civil liberties. Democrats further suggested that the Republicans were advocating in favor of miscegenation and trying to destroy the traditional race relations. They believed they could win, and famously, Lincoln thought that too.

But then the Democratic Party blundered. The convention adopted proposals by Copperheads like Clement Vallandigham calling for a cease fire and a negotiated settlement to the war; but then they selected George McClellan as their candidate. His central argument was that he could win the war sooner and with fewer casualties than Lincoln & Grant. He did not run on a platform of surrender, as is often alleged.

To get the nomination, McClellan had to defeat his opponents Horatio Seymour, New York Governor, and Thomas Seymour, Connecticut governor. Both were real “peace” candidates. Once he was nominated McClellan repudiated the Democratic Party platform. As a result, whatever message intended to be sent to separate their views from Lincoln was garbled. McClellan’s campaign floundered as his repudiation of the peace plank in the Democratic platform provoked discord.

As late as August 23, Lincoln considered it “exceedingly probable” that he would not be reelected. He thought the copperheads would force McClellan into accepting a negotiated settlement, so he made his Cabinet secretly promise to cooperate with McClellan if he won the election to win the war by the time that McClellan will be inaugurated.

Many civil war histories suggest that the victories at Atlanta and the Overland Campaign changed public opinion from the summer of 1864, and surely they did. But a good part of the reason Lincoln was re-elected was that the Democratic Party self-destructed in the campaign.

History books gloss over the closeness of the popular vote. They cite that Lincoln received over 90% of the total electoral votes (212 versus 21 for McClellan). But a 10% margin is relatively close under the circumstances. McClellan ran against Abraham Lincoln, a sitting president, our greatest president, as the war was being won; and garnered 45% of the popular vote. Not only isn’t that pretty under the circumstances of voting against a sitting president in a war (the US has NEVER done this), but the Democratic Party of the 19th century was a fundamentally southern party. In other words, McClellan got 9/20 votes in a population that was northern, running on a platform of stopping the war and reversing emancipation. Moreover, McClellan won 48% of the total vote in a bloc of states stretching from Connecticut to Illinois (Lincoln's home state); Lincoln underperformed in 1864 relative to 1860 in several crucial U.S. states (such as New York, Pennsylvania, and Indiana); and that the Republicans lost the Governorship in his (McClellan's) home state of New Jersey.

What do you think of George McClellan? Let us know below.

Now, read Lloyd’s article on the Battle of Fort Sumter and the beginning of the U.S. Civil War here.

References

Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988. ISBN 0-306-80913-3.

Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0-89919-172-X.

Bonekemper, Edward H. McClellan and failure. McFarland & Co, 2007

Waugh, John C. Lincoln and McClellan: The Troubled Partnership Between a President and His General. Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2010

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.