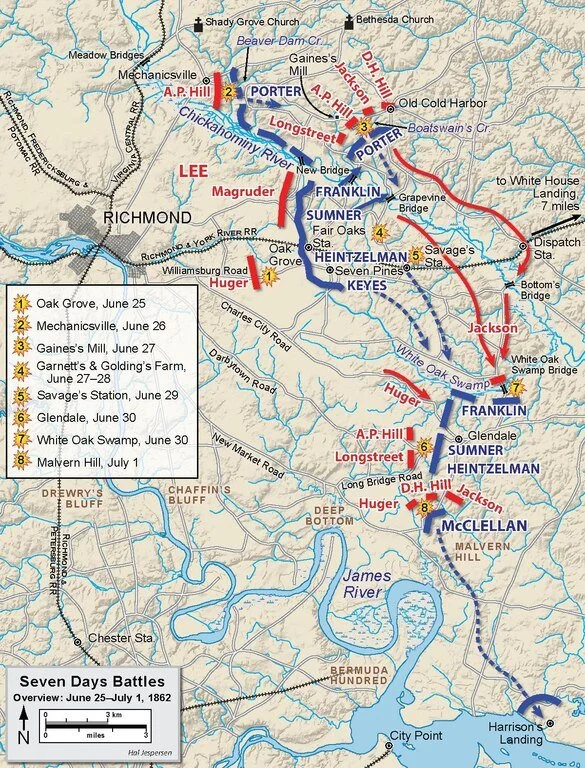

Battle of Gaines’ Mill (June 27, 1862)

Gaines' Mill stands out as the battle during the Seven Days Campaign that most clearly showcased General Lee's capabilities as a military leader. His approach was characterized by significant risk-taking, which underscored his aggressive command style and his readiness to pursue high-stakes opportunities. At this pivotal moment, Lee successfully gathered between 60,000 and 65,000 Confederate troops, while the Union forces, commanded by Fitz John Porter, comprised approximately 34,000 soldiers on the battlefield.

Lee’s perspective. After the indecisive Battle of Oak Grove and Lee’s attack on the Union right at Mechanicsville was repulsed with great losses, witnessed by his president, Lee might have been encouraged to proceed cautiously. However, Lee discerned a potential vulnerability, believing that a retreat following a battle that resulted in a Union victory indicated a strategic weakness. Seizing this opportunity, Lee initiated a formidable attack on Porter's isolated V Corps at Gaines' Mill, recognizing that Porter had retreated to that location and resolved to capitalize on the situation.

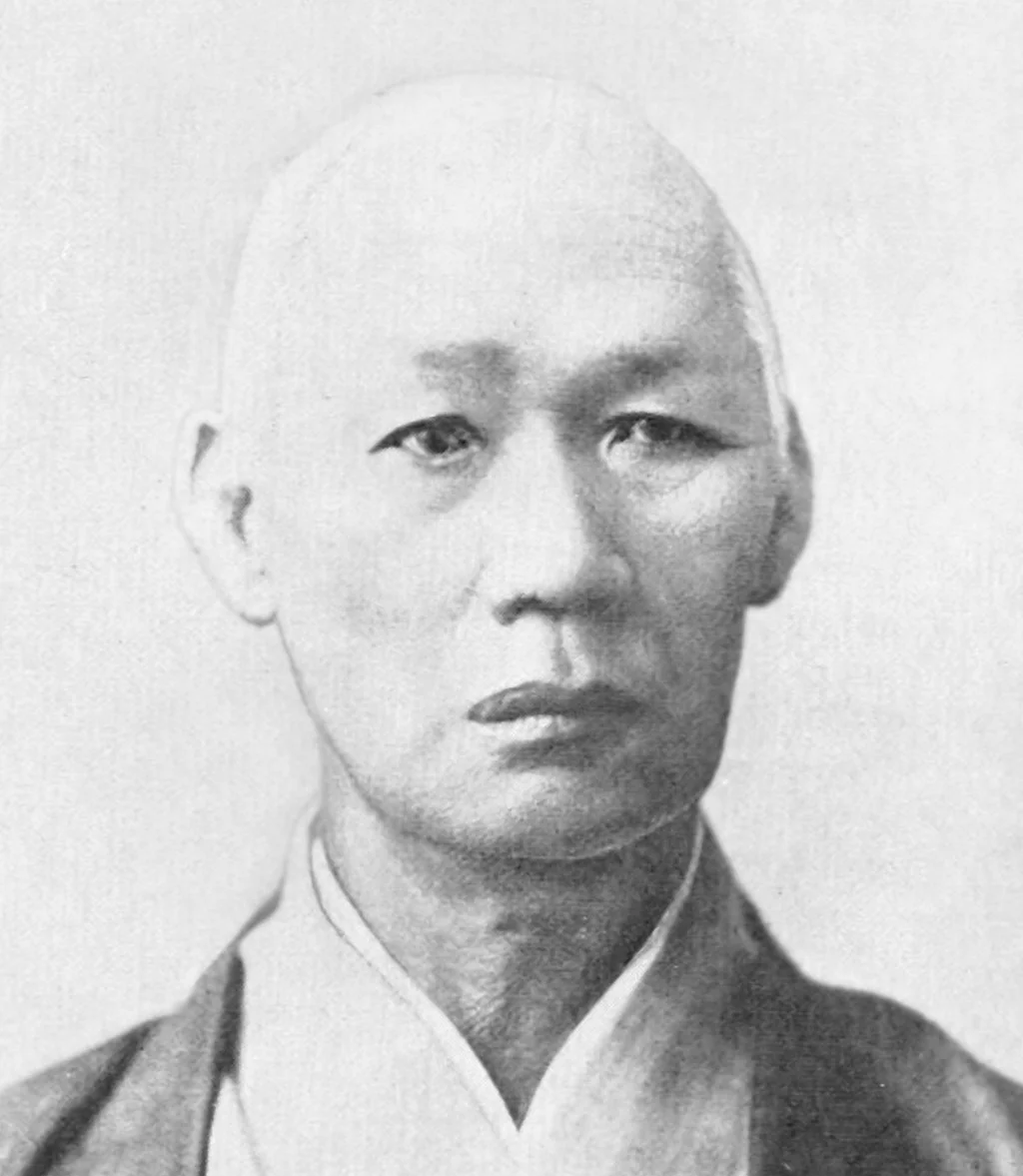

General Fitz John Porter and V Corps had been successful at Mechanicsville defending against Lee’s attack. In the pre-dawn hours of June 27th, McClellan issued a series of urgent directives to his commanders, instructing them to either relocate or abandon their supply trains and to retreat towards the James River, where they would establish a new supply base shielded by artillery support from naval gunboats. McClellan entrusted Porter, his most reliable subordinate, with the critical responsibility of maintaining the rearguard for the Federal army north of the Chickahominy River. Following these orders, Porter retreated eastward, securing a formidable position that overlooked Boatswain’s Swamp, a river boundary that was notably absent from Lee’s maps.

As Lee advanced, he encountered a well-fortified perimeter established by Porter’s forces. The Confederate commander launched renewed assaults, only to discover Union troops strategically positioned behind a stream that Lee had not expected to be present. Lee focused his efforts on the right flank of the Union Army, where General Porter and V Corps found themselves isolated on the northern bank of the Chickahominy River. While Richmond’s elite looked on, Confederate generals A. P. Hill and Richard S. Ewell charged up a steep hill, suffering horrific casualties. Despite Lee's commitment of all six divisions to frontal assaults, the attacks were poorly coordinated and initially failed to dislodge Porter’s men.

Longstreet directed four brigades against the Union left, while D. H. Hill and Richard Ewell also launched attacks across open terrain leading to the woods, brush, and swamps bordering the creek, all of which were met with fierce resistance. The situation shifted when Stonewall Jackson, arriving late and slow to engage, finally entered the fray. A massive frontal assault involving 32,000 men under A. P. Hill ensued, ultimately breaking the Union line. In the wake of this overwhelming offensive, Union commanders Slocum and Sykes were compelled to retreat, marking a significant turning point in the battle.

Gaines' Mill stands out as the sole battle that General Lee could genuinely regard as a tactical victory during the Seven Days Campaign, as the other encounters resulted in either defeats or draws. This battle is notable not only for its immediate outcome but also for its significant ramifications on subsequent military engagements throughout the Civil War. From a leadership perspective, Lee achieved success despite the Confederates' numerous unsuccessful assaults, culminating in a final, coordinated offensive that ultimately shattered the Union defenses.

General Lee undertook significant risks during this battle, notably by dividing his forces against a numerically superior opponent. He concentrated a substantial contingent to launch an assault on the Union's right flank at Gaines’ Mill while assigning a smaller group to defend Richmond and hold back McClellan’s remaining troops south of the Chickahominy River. This strategic division left Richmond vulnerable to potential Union attacks, particularly if McClellan had chosen to exploit this opportunity rather than retreat. A counteroffensive toward Richmond might have overwhelmed Lee’s fragmented forces, jeopardizing the Confederate capital.

Additionally, Lee ordered a large-scale frontal assault against the Union's fortified position on a ridge, which was well-defended by artillery and natural barriers. Such assaults are historically known for their high costs and challenges. The initial Confederate attacks resulted in significant casualties, and further attempts risked not only demoralizing his troops but also depleting his forces without achieving a breakthrough. Furthermore, Lee's strategy relied heavily on the timely arrival of Stonewall Jackson’s corps to strike the Union flank; however, delays due to fatigue and confusion left Lee's initial maneuvers unsupported. By committing nearly all available Confederate units to the battle at Gaines’ Mill, Lee left himself with few reserves to address unexpected developments, which could have severely weakened his army and compromised the defense of Richmond had the assault failed.

Despite the staunch resistance encountered, the Union lines eventually faltered, compelling General McClellan to withdraw across the Chickahominy River. Lee's victory might have been even larger were it not for Jackson's misdirected march and poor staff work. The major assault that Lee unleashed at 7 p.m. breaking the defense could have occurred three or four hours earlier, which would have put Porter in jeopardy, before the reinforcements arrived and obviating the benefit of the cover of darkness.

Lee’s gamble at Gaines’ Mill paid off. His aggressive tactics overwhelmed the Union defenses late in the day, forcing McClellan to retreat across the Chickahominy River and abandon his advance on Richmond. While costly, the victory demonstrated Lee’s willingness to take calculated risks to achieve strategic objectives, a hallmark of his leadership throughout the war.

John Bell Hood led the Texas Brigade that led the charge that broke the Union line near the Watt house. Hood himself survived unscathed, but over 400 men and most of the officers in the Texas Brigade were killed or wounded. He broke down and cried at the sight of the dead and dying men on the field. After inspecting the Union entrenchments, Maj. Gen Stonewall Jackson remarked, "The men who carried this position were truly soldiers indeed."

Jackson was late for a multitude of reasons. During the opening stages of the battle, his men were led down the wrong road, which resulted in an hour-long countermarch. Once on the right road, Jackson’s men encountered roadblocks and sharpshooter fire, which delayed his men even further. By the time Jackson arrived on the field, A.P. Hill’s men were already engaged with the Federals.

Porter had faced multiple waves of attacks and managed to maintain his position. Nevertheless, in order to sustain his defense, he required additional troops. The bulk of McClellan’s forces were stationed across the Chickahominy River, while Jackson’s division was lagging behind, having lost its way en route to the battlefield. After successfully repelling a series of Confederate offensives throughout the afternoon, Porter made a request for reinforcements. McClellan, albeit reluctantly, dispatched only Slocum’s division, which allowed Lee to effectively organize his attacks and finally bring Jackson into the fray. With 16 brigades, totaling approximately 32,000 men, Lee launched an assault against a similarly sized defensive force. As the evening progressed, Porter’s line began to falter, leading to a retreat towards the Chickahominy River.

By 7 p.m., Lee's entire Confederate contingent was assembled and ready to engage the Federal lines. The attack on June 27th, led by A.P. Hill, represented the largest offensive of the Civil War, with over 30,000 troops participating. This assault was nearly twice the size of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg and exceeded Winfield S. Hancock’s attack at the Mule Shoe during the Battle of Spotsylvania, as well as the Confederate charge at the Battle of Franklin.

Despite having a numerical advantage overall, McClellan failed to provide adequate support to Porter during the conflict. While Lee focused nearly his entire army on Porter, McClellan left a significant portion of his forces inactive on the southern bank of the Chickahominy River, thereby missing a critical opportunity to strike at Richmond or Lee’s rear. By bolstering Porter with a substantial number of troops or initiating a simultaneous offensive across the river to target Lee’s left flank, McClellan could have altered the course of the battle and potentially delivered a decisive blow to Lee’s forces. He could have even opted to send a considerable contingent directly to threaten Richmond itself.

Lee’s victory at Gaines' Mill saved Richmond and the Confederacy in 1862. V Corps had been defeated. Two entire Union regiments were surrounded and had to surrender. The tactical defeat led McClellan to retreat. He believed he was in a trap, caught between two rivers. He declared publicly that his campaign against Richmond was over. When General Grant was in almost the same position in 1864 after the Battle of Cold Harbor (the battlefield is almost adjacent), he did not let the opportunity slip away.

Garnett’s & Golding’s Farm (June 27–28, 1862)

While the battle at Gaines's Mill raged north of the Chickahominy River, the forces of Confederate General John B. Magruder conducted a reconnaissance in force that developed into a minor attack against the Union line south of the river at Garnett's Farm. To escape an artillery crossfire, the Federal defenders from Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman’s III Corps refused their line along the river.

The Confederates attacked again near Golding’s Farm on the morning of June 28 but were easily repulsed. These "fixing" actions heightened the fear in the Union high command that an all-out attack would be launched against them south of the river. The action at the Garnett and Golding farms accomplished little beyond convincing McClellan that he was being attacked from both sides of the Chickahominy. McClellan had decided to retreat to his base at the eastern end of the Peninsula on the James River. He called it a “change of base”, but for him, the campaign was over.

Magruder once again employed a ruse of making a lot of noise and marching his men in circles conspicuously to convince McClellan that he had a lot more men than he did. He was clever to recognize that something so simple could be so successful. General Magruder’s nickname was “Prince John” for his dramatic manner and his interest in the theater. His dress and attitude were flamboyant and intended for showmanship. He learned the value of deception in the Mexican War. He had goaded General Butler into attacking him at Big Bethel. He understood intuitively that when intelligence is lacking, commanders make decisions irrationally, and can be deceived by noise and shadows.

Brig Gen Robert Toombs, who had resigned as the Confederate Secretary of State due to his disagreements with the President, was ordered to create a diversion. Instead, the movement turned into a sharp attack. Winfield Scott Hancock led the defense against the attack and stopped it cold.

The two farms were situated close to the Seven Pines battlefield, with Fair Oaks Station located just to the south. These farms can be found approximately a few miles roughly northwest relative to the train station, which lies south of the Chickahominy River. The strategic situation involved General Lee launching a vigorous assault on the Union's right flank in the north while merely feigning an attack on the Union's left. Despite this tactical deception, General McClellan chose to retreat, a decision that was particularly perplexing given the significant losses incurred to secure that territory initially.

The rationale behind McClellan's retreat is difficult to comprehend, as he had several more advantageous alternatives available for a potential repositioning. The retreat necessitated the movement of not only his infantry but also a considerable amount of artillery, including 16 siege guns, along with 3,800 wagons and over 2,500 cattle. Viable options for alternative bases included White House Landing and West Point, advancing towards Fort Monroe, or maintaining his position on the right while planning an offensive against Richmond. Opting to move south across the Peninsula towards the James River not only represented a strategically weak choice but also posed logistical challenges due to the limited road access in that direction, providing Lee with the opportunity to launch an attack on McClellan's rear guard.

Battle of Savage’s Station (June 29, 1862)

McClellan's over-reactions during the encounters at Mechanicsville and Golding's Farm, which, were not classified as defeats yet prompted withdrawals, captured Lee's attention. Recognizing a potential opportunity to destroy McClellan's entire army, Lee formulated a comprehensive plan for pursuit. It is important to highlight that this approach was notably aggressive; he could have simply declared victory without further action. However, Lee was in the hunt of a more significant objective.

To execute his strategy, Lee dispatched the divisions of James Longstreet, A. P. Hill, and Theophilus H. Holmes to the southeast, positioning them to target McClellan's left flank. He instructed Stonewall Jackson, who was leading his division, along with the divisions of D. H. Hill and Brigadier General William H. C. Whiting, to repair a bridge over the Chickahominy River and subsequently launch an attack on McClellan's forces from the north. Additionally, Lee commanded Brigadier General John B. Magruder to advance his division along the Richmond and York River Railroad to engage McClellan's rearguard.

As McClellan found himself in a full retreat, he left behind a rearguard consisting of three corps: Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner’s 2nd Corps, Brigadier General Samuel P. Heintzelman’s 3rd Corps, and Brigadier General William B. Franklin’s 6th Corps, stationed near Savage’s Station. Interestingly, McClellan did not designate an overall commander to oversee the operations of his rearguard, which could have provided a more coordinated defense during this critical battle.

Savage’s Station was a stop on the Richmond and York River Railroad, acting as a depot for McClellan’s supply lines. This location also hosted a Union field hospital, where medical personnel attended to approximately 2,500 soldiers who had sustained injuries during the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. As Magruder’s division advanced eastward along the railway, the Federal forces were engaged in preparations for evacuation, systematically destroying any supplies that could potentially benefit the Confederates.

On June 29, at 9 a.m., Magruder initiated combat with Sumner at Orchard Station, located two miles west of Savage’s Station. Although Sumner's forces outnumbered the Confederates by a margin of 26,000 to 14,000, Magruder anticipated reinforcements from Jackson on his left flank and Huger’s division on his right. However, Jackson failed to arrive on time, having misunderstood his orders and remained positioned north of the Chickahominy River, while Huger was not present on Magruder’s right as expected.

Concerned that his outnumbered troops might be vulnerable to a Federal assault, Magruder sought additional support. In response, General Lee provided him with two brigades from Huger’s division, stipulating that these reinforcements would need to be returned if no attack occurred by 2 p.m. As the designated time arrived and elapsed without incident, Magruder was compelled to send back the additional forces. Confronted with the challenging situation of engaging a significantly larger enemy contingent, he opted to delay his offensive until 5 p.m.

There were rumors regarding Magruder's potential consumption of alcohol, largely stemming from his distinctive character, although substantial evidence to support these claims is lacking. At this critical juncture, he issued a series of perplexing orders for an assault, which may have been influenced by morphine administered to alleviate severe indigestion. This possible impairment in judgment led to the issuance of unclear and hesitant commands, resulting in less than half of his available troops participating in the subsequent confrontation.

With no overall commander in charge of the federal rear guard, Heintzelman decided that two divisions were enough to hold off Magruder and unilaterally marched his men south to join the main army, without informing Sumner or Franklin. After learning of Heintzelman’s departure, Sumner’s directives proved even more cautious than Magruder’s. When Magruder finally attacked, Sumner deployed only ten of his twenty-six regiments during the engagement.

After several hours of intense fighting, the engagement concluded around 9 p.m. as darkness fell and violent thunderstorms erupted. While the combat was fierce at times, the outcome remained ambiguous. The Confederates incurred approximately 450 casualties, whereas the Federals faced nearly 900 losses; however, General Magruder was unable to dislodge General Sumner from his position.

That evening, General Lee sent a dispatch to Magruder expressing his disappointment regarding the lack of progress made in pursuing the enemy: “GENERAL, I regret much that you have made so little progress today in pursuit of the enemy. In order to reap the fruits of our victory the pursuit should be most vigorous. I must urge you, then, again to press on his rear rapidly and steadily. We must lose no time, or he will escape us entirely.” Despite Lee's insistence, Sumner managed to evade capture. Anticipating the arrival of Jackson during the night, McClellan instructed Sumner to withdraw from Savage’s Station, leaving behind 2,500 soldiers and medical personnel at the Union field hospital. By noon the following day, the majority of McClellan’s army had successfully crossed the White Oak Swamp, thereby eluding Lee’s encirclement.

Battle of Glendale (June 30, 1862) & Frayser’s Farm or White Oak Swamp

Following the defeat of the Union V Corps at Gaines’ Mill on June 27, General McClellan made the strategic decision to abandon his campaign aimed at capturing Richmond. He directed his forces southward toward the James River, seeking refuge and resupply from the naval vessels stationed there. Meanwhile, General Lee recognized McClellan's retreat and perceived an opportunity for a significantly larger victory.

On June 30, three divisions of Confederate troops converged on the retreating Union army at the crossroads near Glendale. Major Generals James Longstreet and A. P. Hill initiated assaults both north and south of Long Bridge Road, targeting the V Corps Pennsylvania Reserves division commanded by Brigadier General George A. McCall. In response, the II Corps division under Brigadier General John Sedgwick, along with the III Corps divisions led by Brigadier Generals Phil Kearny and Joseph Hooker, moved to reinforce McCall. Despite their efforts, Longstreet and Hill managed to momentarily breach the Federal line and capture McCall.

Lee attempted to orchestrate a coordinated strike against the Union rear as McClellan's forces retreated toward the James River. However, the Confederate forces suffered from a lack of coordination once again. Longstreet, in particular, deployed his troops in a fragmented manner rather than as a unified assault. Huger was expected to be part of one of four attacking columns aimed at the Union lines, traveling along the Charles City Road with William Mahone in the lead. Unfortunately, they encountered a blockade of felled trees just two miles away. Although the obstruction could have been cleared within a few hours, Mahone proposed the construction of a two-mile parallel road through the woods. This decision ultimately prolonged their advance, as the Union army continued to fell more trees along the route, preventing Huger from reaching the intended position.

Maj. Generals James Longstreet and A. P. Hill successfully breached the Federal defenses, leading to the rout of the Pennsylvania Reserve division along with other brigades. Their advance brought them close to the Frayser farm, which is situated near the residence of R. H. Nelson. In response, Union forces, commanded by Brig. Generals Joseph Hooker and Phillip Kearny, launched counterattacks that effectively safeguarded the Union's line of retreat along the Willis Church Road. By nightfall, the Federals managed to maintain control over this critical route, which provided access to the remainder of the Union army, allowing them to withdraw to a more defensible position at Malvern Hill.

In terms of troop strength, the Confederates had a slight numerical advantage over the Union forces, with approximately 45,000 soldiers compared to 40,000. The casualty figures were nearly equal, with both sides suffering around 3,700 losses. This engagement, like many others, ended inconclusively, with the Union army narrowly averting a potential disaster.

At Glendale, General Lee's strategic ambitions faltered. General Magruder spent the day maneuvering in the rear of the Confederate Army without engaging in the attack. Meanwhile, General Jackson remained north of the White Oak Swamp, preoccupied with a futile artillery exchange with the Army of the Potomac's VI Corps. Despite the discovery of viable fords by some of his officers, Jackson's inaction during the intense fighting nearby left Longstreet and A. P. Hill's divisions to shoulder the primary burden of the battle. Although their initial assaults succeeded in breaching General George McCall's division and even capturing McCall himself, Union forces under Generals Hooker, Kearny, and Sedgwick managed to halt their advance. The fierce combat, characterized by hand-to-hand encounters, continued until darkness descended, ultimately preventing Longstreet and Hill from seizing the crucial crossroads and allowing McClellan’s army to maintain a strong defensive position against Lee’s disorganized attacks.

While the battle was tactically inconclusive, it represented a strategic victory for the Federal forces. General Lee was unable to fulfill his goal of obstructing the Federal retreat and significantly damaging or annihilating McClellan's army. In contrast, despite suffering substantial losses, the Federal troops successfully repelled the Confederate attacks, enabling the majority of the Army of the Potomac to safely navigate through and establish strong defensive positions at Malvern Hill.

McClellan's absence from the battlefield was once again evident, as he delegated the management of the conflict to his subordinates. During the Battle of Glendale he remained five miles away, positioned behind Malvern Hill, lacking telegraphic communication and too far to effectively direct his forces. His focus appeared to be on retreating to the James River, which ultimately represented a lost opportunity for the Union. A more assertive approach at Glendale could have dealt a significant blow to Lee's army and possibly curtailed the Confederate pursuit. General Porter assumed the role of the de facto field commander during this engagement.

Malvern Hill (July 1, 1862)

On July 1, 1862, after enduring six days of intense combat, the Army of the Potomac made its way to the James River. With confidence bolstered by the presence of nearby naval gunboats, Major General George McClellan's forces established a position on Malvern Hill, situated one mile from the river at an elevation of 130 feet. McClellan took decisive action by fortifying the hilltop with artillery batteries to protect the open fields below, while strategically positioning his infantry with the V Corps on the western slope and the III and IV Corps on the eastern side, ensuring a robust reserve in the rear. Confederate General Robert E. Lee aimed to weaken the Union defenses through a sustained artillery barrage prior to launching an infantry assault. At approximately 1:00 p.m., both armies commenced an artillery exchange, which ultimately proved to be largely ineffective.

Over four hours, a series of miscalculations in strategy and communication led to three unsuccessful frontal assaults by Lee's forces, which charged across open terrain without the support of Confederate artillery. This approach, characterized by direct infantry attacks against well-fortified Union positions, proved ineffective in the context of modern warfare, where artillery and rifled weapons had transformed combat dynamics.

As Lee directed his infantry to advance, the attacks lacked proper coordination, resulting in staggered assaults that faltered before reaching the hill's summit. The initial charge was led by General Lewis Armistead, who found his forces immobilized midway up the hill. Following this, General Magruder launched an attack with his division, which included brigade leader General Barksdale. Initially hesitant due to the perceived ineffectiveness of the artillery fire, D.H. Hill delayed his support for two hours before finally ordering his men to engage in five separate, uncoordinated attacks.

The Union's defensive position was formidable, featuring nearly one hundred artillery pieces strategically positioned along the plateau's summit, with an additional 150 guns held in reserve, complemented by three infantry divisions prepared for combat. In contrast, the Confederate forces were only able to concentrate a maximum of 15 artillery pieces on each flank, which were swiftly neutralized by the Union's superior artillery. The lack of effective communication and ambiguous orders among the Confederate ranks led to devastating losses. The effectiveness of the Federal artillery proved to be the pivotal element in the conflict, successfully repelling every Confederate assault and securing a tactical victory for the Union.

About 55,000 soldiers took part on each side, employing more than two hundred pieces of artillery and three warships. The battle resulted in over 5,600 casualties for the Confederates, representing approximately 10% of their forces, while the Union experienced about 3000 casualties. D.H. Hill, witnessing the devastation, expressed his dismay by stating that the events on the battlefield resembled murder rather than warfare. Surveying the carnage on the bloody field, he remarked disgustedly, “it was not war, it was murder.”

During the Battle of Malvern Hill, General McClellan was on a gunboat, the USS Galena, which at one point was ten miles away, down the James River. His distance rendered him incapable of effectively managing the battle, leading to criticism during the 1864 presidential campaign, where editorial cartoons mocked his preference for the safety of the vessel while conflict raged nearby. Consequently, the responsibility for commanding the army fell to Brigadier General Fitz John Porter, the commander of the V Corps.

Brig Gen Henry Hunt, emerged as the pivotal figure in this confrontation. Colonel Hunt was on McClellan's staff at Malvern Hill and is credited for the gun placement at Malvern Hill. Lt. Col. Webb probably assisted him. Hunt played a crucial and decisive role through his masterful use of artillery. Though not a frontline combat commander in the traditional sense, his contributions at Malvern Hill were pivotal to the Union victory. Hunt selected and arranged about 250 Union cannons on high ground at Malvern Hill, using the terrain to his advantage. He deployed 40 pieces of artillery along the ridge by Willis Church road, covering every direction the Confederates would attack. He established overlapping fields of fire and positioned batteries so they could mutually support one another and repel infantry assaults. He insisted on fire discipline, ordering that cannons only fire at optimal range and at designated targets, not in an uncontrolled barrage. This preserved ammunition and ensured maximum effectiveness during Confederate charges.. While the Union gunboats contributed somewhat, it was Hunt’s artillery placement that resulted in victory. General Lee proceeded with his assaults without conducting a thorough reconnaissance of the enemy's defenses. Undertaking such an assessment would have necessitated at least a half-hour journey to the front lines. Aware that this was his final opportunity to confront McClellan, Lee relied heavily on the intelligence provided by his subordinates, which historians believe may have underestimated the fortifications.

The engagement at Malvern Hill was a definitive victory for the Union forces. Following multiple failed attempts to penetrate the Union defenses, General Lee decided to cease further attacks as darkness descended, effectively concluding the battle. Simultaneously, McClellan directed his troops to retreat toward Harrison’s Landing along the James River, thereby marking the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles.

Summary & Implications

“I, Philip Kearny, an old soldier, enter my solemn protest against this order for retreat. We ought instead of retreating should follow up the enemy and take Richmond. And in full view of all responsible for such declaration, I say to you all, such an order can only be prompted by cowardice or treason.”

When General Lee assumed leadership of the Army of Northern Virginia following the wounding of General Joseph E. Johnston, the Union army was perilously close to Richmond, just four miles away. Lee successfully repelled Union forces, preventing their advance toward Richmond,. The defeat for the Union in the Peninsular Campaign not only delayed their victory for two years but also resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives.

Over a single week, Lee orchestrated a series of daily engagements in a rapid campaign. Employing a strategy he would later replicate, he audaciously split his smaller army to launch attacks at multiple locations, compelling McClellan to retreat from Richmond and back down the peninsula. The ambitious campaign of the so-called 'Young Napoleon' ultimately faltered, while Lee's actions preserved Richmond. McClellan's forces remained at Harrison’s Landing for several weeks, ultimately returning to Washington with little to show for their efforts.

The Seven Days had produced unimaginable carnage. It had been the bloodiest week in American history up to that time, producing more than 34,000 casualties (19,000 Confederate, 15,000 Union). The reversal of fortune represented the first significant turning point in the conflict. For nearly a year, the Union forces, particularly in the Western Theater, had advanced with seemingly unstoppable momentum toward victory, and had even reached the outskirts of Richmond. As news circulated, both Americans and international observers began to form expectations about the war's conclusion, with The New York Times suggesting that hostilities might cease by Independence Day.

However, the events of June 1862 revealed that the Confederate cause had merely been waiting for a leader of exceptional skill to change its trajectory. The emergence of such leadership altered the dynamics of the war, demonstrating that the outcome was far from predetermined. The initial confidence in a swift Union victory was challenged, as the realities of warfare unfolded, reshaping the perceptions and strategies of both sides in the ongoing conflict.

While McClellan’s army performed well tactically in several engagements, particularly at Mechanicsville and Glendale, his reluctance to act decisively and his fixation on retreating to a secure position cost him the chance to gain ground at any of the Seven Days Battles. A more aggressive commander might have turned one or more of these battles into a decisive Union victory, potentially ending the Peninsula Campaign on favorable terms. McClellan had opportunities to achieve significant victories, but his cautious approach and mismanagement of certain engagements prevented him from capitalizing on these moments.

The retreat made Lincoln so angry that he suspended McClellan from command of all the armies, leaving him only the Army of the Potomac. McClellan blamed the War Department, Lincoln, and the Secretary of Defense for his defeats. McClellan distanced himself from his defeat. During the last engagements of the Seven Days, he boarded a gunboat on the James River, watching events from afar and letting one of his corps commanders, Fitz-John Porter, lead the fighting. Typically, McClellan blamed others for the setback. He bitterly wrote to Stanton: ‘If I am to save this army, it will be no thanks to you or any other person in Washington. You have sacrificed this army.’

Although Lee deserves the accolades he has received as a master tactician for taking an aggressive stance with a smaller force to ward off a much larger one, the military reality is that all of these fights were essentially draws; one was a Rebel victory, at least two more of a Union victory. And the losses were staggering. General Lee did not yet have his subordinates in control. At this stage of the war, no one had the experience or expertise needed to coordinate complex offensives, especially in an army with a brigade-centered structure. That was about to change.

Nevertheless, Robert E. Lee’s decision to adopt an aggressive approach during the Seven Days Battles was informed by a combination of strategic insight, intelligence, and a keen understanding of his opponent. Lee calculated that aggressiveness would succeed. He recognized that George B. McClellan was a cautious and risk-averse commander. McClellan’s hesitation to act decisively during the Peninsula Campaign gave Lee confidence that an aggressive strategy could unnerve and outmaneuver him. Lee understood that McClellan was more likely to retreat than to respond with bold counterattacks.

Confederate Intelligence also played a role. Lee had access to information that revealed McClellan’s slow movements and defensive mindset. Confederate cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart’s famous ride around McClellan’s army in mid-June 1862 provided valuable reconnaissance, showing that McClellan’s flanks were exposed and his forces were spread thin. Lee believed that McClellan would not expect an offensive campaign from a Confederate army that was perceived as outnumbered and on the defensive. By taking the initiative, Lee hoped to disrupt McClellan’s plans and seize the psychological advantage. Lee understood the importance of logistics to McClellan’s campaign. By attacking his supply lines, he threatened the entire army beyond a large battle, compelling McClellan to abandon his advance on Richmond.

Aftermath

General Kearny would be killed later that year at the Battle of Chantilly.

General Hancock emerged as an essential figure, significantly influencing the Union's triumphs at both Gettysburg and the Overland Campaign. In 1880, he sought the presidency as the Democratic Party's nominee but was narrowly defeated by James Garfield, another former Union general, with a margin of just 39,000 votes out of a total of 8.9 million cast.

Robert Rodes participated in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, later playing a pivotal role at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg before being killed at Third Winchester. He is often regarded as one of the most promising Confederate major generals whose potential was not fully realized, having received his training at VMI rather than West Point, which was favored by President Davis.

Benjamin Huger was deemed too old for command and pushed out, to the trans-Mississippi. His failures to appear in a timely way were interpreted as a lack of initiative.

General Magruder was banished to command in the far west. Lee had no tolerance for anyone who couldn’t control himself, and flamboyance would seem to be the antithesis of General Lee. Histories of the war often assert that Magruder was prone to drunkenness on duty and that his actions at Savage’s Station allowed a large portion of the AoP to escape. There isn’t much documentation of his being inebriated, and as the narrative suggests, there were plenty of mistakes made by just about everyone involved in this battle. He spent the remainder of the war administering the District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona and the Department of Arkansas; in his tenure, Magruder lifted the naval blockade over Galveston and recaptured the city in 1863. After surrendering the Trans-Mississippi Department in June 1865, Magruder fled to Mexico. He worked in an administrative role under Emperor Maximillian I before returning to the United States in 1867.

D.H. Hill served with distinction in these battles; however, his temperament did not align with that of General Lee. Consequently, he was assigned the task of defending Richmond during the forthcoming campaign. Following the incident known as the Lost Order at Antietam and the death of his brother-in-law, Jackson, at Chancellorsville, Hill found himself once again stationed in Richmond for the Pennsylvania Campaign before being reassigned to General Bragg in the Western Theater. This pattern of leaving behind those he could not rely on was characteristic of Lee's approach to commanders he deemed untrustworthy.

The performance of Stonewall Jackson during the Seven Days battles was notably poor. He arrived late at Savage's Station and failed to utilize fording sites to cross White Oak Swamp Creek at Glendale, instead spending hours attempting to reconstruct a bridge. This miscalculation resulted in a limited contribution to the campaign, as he was relegated to an ineffective artillery exchange and missed a critical chance to make a decisive impact. His absence left A.P. Hill and Longstreet to fend for themselves in their assaults. The great Stonewall Jackson was essentially a non-factor in this particular campaign.

Longstreet, in the Peninsula Campaign, had operational command of over half the Confederate Army, but his efforts had a mixed impact, with great successes and failures. Longstreet’s biggest contribution in the Peninsula was to help General Johnston conduct a sound retrograde back toward Richmond, and try to improve the organization and command and control of the only brigade centric Confederate army in a time when both sides were still learning how to put together effective units and then fight them together. When Lee took over some of this had been done, and Longstreet helped Lee to reach a good divisional structure.

As the command structure evolved, Longstreet and Jackson were formally appointed as Lee's immediate subordinates, serving as Corps commanders, while A.P. Hill's reputation significantly improved in Lee's eyes. The centralization of command proved to be an effective strategy for managing an army with a smaller staff. These adjustments in leadership would mark a period of remarkable success for Lee's army over the next eleven months, ultimately leading to some of General Lee's most notable achievements on the battlefield.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

References

· Matthew Spruill, Decisions of the Seven Days. Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 2021.

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gaines-mill

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-battle-gaines-mill

· https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/seven-days-battles/

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/seven-days-battles

· https://www.historynet.com/details-bridging-the-chickahominy-river.htm

· https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1116765.pdf

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/seven-days-battles

· https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-oak-grove/

· https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-savages-station/

· https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/gainess-mill-battle-of/

· James M McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom. Oxford University Press, 1988.

· Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative. Volumes 1-3. Random House, 1963.

· Crenshaw, Doug. Richmond Shall Not Be Given Up: The Seven Days' Battles, June 25–July 1, 1862.Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017.