Throughout history, fortifications have served as physical manifestations of a society's desire for security, power, and territorial control. From the earliest wooden palisades of the Neolithic era to the massive stone castles of the medieval period, defensive architecture has evolved in response to changing technologies, political structures, and threats. Many of these fortifications still rise above the landscape today, while others lie buried beneath layers of earth and centuries of development, offering clues to archaeologists about the ancient world's priorities and conflicts.

Terry Bailey explains.

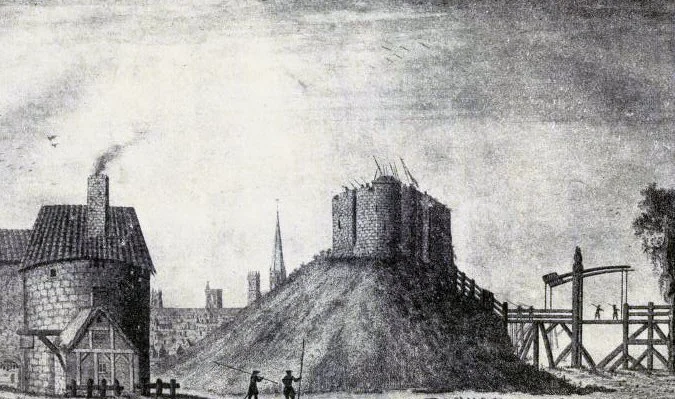

York Castle (Clifford's Tower) in 1644.

Early fortified settlements

The need for protection from rival tribes, wild animals, or marauding raiders spurred the earliest humans to construct rudimentary fortifications. Archaeological evidence from Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey, dating back to around 7500 BCE, suggests that early urban settlements employed dense housing patterns and elevated entrances as a form of communal defense. Although not a fortification in the traditional sense, the lack of streets and the rooftop-only access served to repel invaders.

The first recognizable fortifications, constructed with the intent to produce a clear defensive perimeter, appear during the Neolithic period. At sites like Jericho, one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities, archaeologists have uncovered a massive stone wall dating to around 8000 BCE, complete with a round tower over 8 meters high. This structure likely protected the community from floods or hostile groups and stands as evidence of early human instinct for security.

Bronze Age walls and citadels

As societies grew more complex during the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BCE), fortifications became increasingly sophisticated. Many were constructed using earthworks, stone, and timber. Defensive ditches and ramparts encircled hilltop settlements, particularly in Europe.

A notable example is Mycenae, a powerful city-state in ancient Greece. By the 14th century BCE, its rulers had constructed massive Cyclopean walls, named for their enormous limestone blocks, so large that later Greeks believed only the mythical Cyclopes could have built them. Mycenae's Lion Gate, adorned with a stone relief of lions, remains standing and is one of the most iconic survivals of ancient fortification.

Near East, cities like Babylon were surrounded by formidable walls. King Nebuchadnezzar II (6th century BCE) expanded the walls of Babylon, which Greek historians like Herodotus claimed were so wide that chariots could race atop them. However, modern scholars question this scale, the archaeological remains nonetheless show double and triple layers of defense, with crenellated towers and fortified gates such as the Ishtar Gate, now reconstructed in Berlin's Pergamon Museum.

Side note:- Today it is well recognized that the historical writings of Herodotus were heavily laced with artistic license

Iron Age hill forts and ramparts

With the arrival of the Iron Age (c. 1200 - 600 BCE), tribal societies in Europe began constructing hill forts, which were fortified enclosures built on elevated ground to command views of the surrounding landscape. These were often surrounded by dry-stone walls, timber palisades, and deep ditches.

In Britain, examples such as Maiden Castle in Dorset and Danebury Hillfort in Hampshire provide extensive archaeological evidence of Iron Age fortifications. Maiden Castle, one of the largest hillforts in Europe, features multiple concentric ramparts and ditches, which would have been topped with wooden palisades. Excavations have revealed signs of violent conflict, including weaponry and evidence of burning, indicating their active use in war.

Further afield, (large fortified settlements) emerged in the Celtic world during the late Iron Age. Sites like Bibracte in modern France combined residential, commercial, and defensive functions, surrounded by stone walls that reflected both technological innovation and social complexity.

The Roman military machine

No civilization better epitomized systematic military fortification than ancient Rome. Roman engineers constructed a vast network of forts (castra), walls, and border defenses that spanned the empire.

Standardized fort blueprints included rectangular layouts with rounded corners (similar to modern-day forts), stone walls, watchtowers, and barracks within. A well-preserved example is Housesteads Roman Fort along Hadrian's Wall in northern England, which was part of a continuous defensive structure begun in 122 CE to mark the empire's northern boundary. Many stretches of Hadrian's Wall remain visible today, with watchtowers and milecastles dotting the windswept hills.

Another notable example is Vindolanda, located just south of Hadrian's Wall. Layers of occupation have revealed multiple phases of construction, including wooden forts predating the stone phase, as well as thousands of writing tablets, providing a rare glimpse into daily life at a Roman military outpost.

The age of castles; medieval fortifications

With the fall of Rome and the fragmentation of Europe, defensive architecture took on new forms in response to feudal power structures and frequent warfare. The castle emerged as both a military stronghold and a symbol of lordly authority.

The earliest medieval castles were motte-and-bailey structures, popularized in Norman-controlled areas following the conquest of England in 1066. These consisted of a wooden or stone keep perched on a raised mound (the motte), accompanied by a courtyard (the bailey) enclosed by a wooden palisade and ditch. Clifford's Tower in York originated as a wooden structure, with later stone enhancements.

As military tactics evolved, so did castles. From the 12th century onward, stone became the standard, and concentric fortifications with curtain walls, crenellations, and moats emerged. Castles like Dover Castle in England or Carcassonne in France, still standing in remarkable condition demonstrate the complexity of medieval defense systems. Features like machicolations (openings through which defenders could drop stones or boiling oil), arrow slits, and drawbridges became common.

The Tower of London, begun by William the Conqueror in the late 11th century, evolved over centuries from a simple keep into a formidable fortress complex with multiple layers of defense. Its central White Tower still dominates the skyline, surrounded by curtain walls and bastions that testify to successive waves of expansion.

Archaeological legacies; fortifications beneath the feet

While many castles and city walls survive above ground, even more remain buried beneath centuries of sediment and urban development. Tell sites in the Middle East, such as Tell Brak in Syria or Tell es-Sultan at Jericho, consist of accumulated layers of occupation where ancient fortifications are discovered at lower strata, sealed by later civilizations.

Modern techniques like ground-penetrating radar, LIDAR, and aerial photogrammetry have revolutionized the discovery and mapping of these ancient defenses. At Troy in western Turkey, Heinrich Schliemann's 19th-century excavations revealed multiple layers of city walls, some dating back to the late Bronze Age, indicating a continuous occupation of the site and once thought to be myth, now recognized as an archaeological fact.

In Scandinavia, Viking ring fortresses such as Trelleborg in Denmark, dating to the 10th century, were only rediscovered through aerial surveys and excavations. These perfect circular enclosures with symmetrical gates and wooden palisades were highly advanced for their time and demonstrate the military precision of Viking engineers.

All these sites simply show that the history of fortification is as much a story of evolving engineering as it is of social and political transformation. As materials improved and societies grew more organized, so too did the scale and complexity of their defensive architecture. While many ancient palisades and timber walls have rotted into obscurity, their stone successors, ramparts, towers, and battlements continue to shape the landscapes and cities of the modern world.

From the buried remains of prehistoric hillforts to the tourist-drawing towers of medieval castles, fortifications remain some of the most enduring monuments of human civilization. They speak not only of the human fear of conflicts but also of the ingenuity, determination, and capacity for monumental construction.

In conclusion, the evolution of fortifications reflects far more than a mere arms race between attackers and defenders, it charts the rise and fall of civilizations, the march of technology, and the changing fabric of human society. Each wall, ditch, bastion, and barbican tells a story, not just of conflict, but of ingenuity, adaptability, and the deep-seated human desire for permanence and protection.

From the early walls of Jericho and the tower-studded ramparts of Babylon to the moated castles of medieval Europe and the precise, measured castra of Rome, fortifications reveal how communities confronted insecurity in both practical and symbolic terms. They were not only shelters against physical threats but also statements of power, order, and control. The very act of building a fortification, whether a Bronze Age citadel, an Iron Age hillfort, or a Norman castle was a declaration of intent: to claim and hold territory, to deter rivals, and to withstand the unknown.

Moreover, these structures evolved hand-in-hand with developments in military tactics, political authority, and material science. The shift from earth and timber to dressed stone, the introduction of concentric defenses, and the incorporation of innovations such as drawbridges, towers, and bastions all point to a dynamic interplay between builders and besiegers.

Fortifications were never static; they were constantly adapted, expanded, and sometimes abandoned as the tides of history shifted. Even in the modern era, the ghostly outlines of these ancient structures, revealed through archaeology, satellite imaging, and painstaking excavation are a reminder that beneath the foundations of modern cities and towns lie the remnants of humanity's earliest efforts to shape and safeguard its future.

Discoveries such as the multi-layered defenses at Troy, the perfect geometry of Viking ring forts, or the massive Cyclopean walls of Mycenae underscore how sophisticated early societies truly were, and how much effort and resources they devoted to their protection.

Today, as individuals or researchers marvel at restored castles or peer over ancient battlements worn by time, as a species we are not merely looking at relics of warfare, we are witnessing the resilience of human civilization, etched into earth and stone. Fortifications, in their many forms, represent a universal language of resistance and survival, transcending geography, culture, and chronology. They are lasting proof of the lengths humanity and cultures have gone to safeguard their people and citizens, while asserting their dominance, and expressing their identity through architecture.

In a world increasingly defined by fluid borders and new forms of conflict, cyber, ideological, and environmental, the ancient fortifications that still dot the landscape serve as poignant reminders of a time when stone walls and high towers stood between safety and peril. Their enduring presence is a bridge between the distant past and the present, inviting an appreciation of craftsmanship, in addition to, the historical importance, along with reflections on what it means to build, to defend, and ultimately, to endure.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Notes:

The walls of Jericho, long immortalized in biblical stories and tradition as having "come tumbling down" at the blast of Israelite trumpets, have been a subject of both faith and archaeological inquiry. While the dramatic biblical account attributes their collapse to divine intervention during Joshua's conquest, archaeological evidence has suggested a more grounded explanation. The technique of undermining, where besiegers dig beneath a wall to weaken its foundations, may have been responsible for their fall.

Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the site of ancient Jericho, have uncovered significant remains of fortification systems, including massive stone retaining walls and mudbrick superstructures that once stood atop them.

Kathleen Kenyon's work in the 1950s revealed a collapsed pile of mudbrick debris at the base of the retaining wall on the western side of the site. This discovery pointed to a sudden structural failure of the upper walls. Rather than the result of an earthquake or simple erosion, archaeologists have interpreted this pattern of collapse as indicative of human action, specifically, undermining.

Undermining involved digging tunnels under a wall and setting fire to supporting wooden beams, causing the earth and wall above to collapse. This was a known siege technique in the ancient Near East. In Jericho's case, if besieging forces had tunneled beneath the mudbrick structures resting on the stone base, the sudden release of pressure would have caused the entire superstructure to slide outward and down, resulting in the kind of massive debris field Kenyon uncovered. The consistency and location of the rubble support the theory of internal weakening and outward collapse, which aligns with the effects of undermining.

Thus, while the biblical narrative presents the destruction of Jericho's walls as a miraculous event, the archaeological record offers a plausible military explanation rooted in ancient siegecraft. The evidence of collapsed mudbrick walls at the base of the fortifications suggests that undermining, rather than trumpet blasts, was likely the true cause behind the dramatic fall of one of history's most legendary walled cities.

Tell sites

Characteristics of Tell Sites:

Layered occupation:

A tell forms when successive generations build new structures on top of the ruins of older ones, often using mudbrick, which erodes and compacts over time.

Each layer (or stratum) represents a different period of occupation, producing a chronological sequence that archaeologists can study.

Mound shape:

Tells are typically conical or flat-topped mounds, with steep sides formed by centuries of erosion and debris accumulation.

They often stand prominently above the surrounding landscape.

Rich in cultural material:

Tells are archaeological goldmines, containing artefacts, architecture, burial remains, tools, and ceramics that reveal much about ancient daily life, trade, and society.

Examples of famous Tell sites:

Tell Brak in Syria

Tell el-Hesi in Israel (one of the first to be scientifically excavated)

Tell Halaf and Tell al-Rimah in Mesopotamia

Çatalhöyük in Turkey, a Neolithic mega-settlement and one of the oldest known tells

Archaeological importance:

Excavating a tell site allows archaeologists to trace the long-term development of a community or region.

The stratigraphy within a tell is crucial for relative dating, where deeper layers are generally older than those above.

In short, tells are time capsules of human occupation, offering a vertical record of history at a single geographic point.

The root of the word palisades

The word "palisades" comes from the Middle French word palisade, which itself is derived from the Provençal (palisada) and ultimately from the Latin word palus, meaning stake.

Therefore, originally the Latin word palus, meaning stake or "post, Latin (plural), pali, stakes (used to construct barriers), and late Latin verb, palicium meaning a fence made of stakes, passed to old French: palis a stake or fence, through middle Middle French, palisade meaning a defensive fence made of stakes.

Eventually into English in the late 16th century, as palisade, a fence of wooden stakes or iron railings fixed in the ground, used as a defensive structure.

Thus originally, a palisade referred to a defensive barrier or fence made of pointed wooden stakes, often driven into the ground in close succession. Used from ancient and medieval times to fortify military camps, towns, or temporary strongholds.

The term later expanded to describe natural formations resembling fences of stakes, such as cliffs or steep rock faces, hence, names like The Palisades along the Hudson River in the United States.

The root of the word castle

The word "castle" has a rich etymological history that reflects its military and feudal significance throughout the centuries.

The word castle finds its root in Latin, originating from the Latin term castellum, which is a diminutive of castrum, meaning "fort" or "military camp."

Castrum refers broadly to Roman military encampments or forts, therefore, Castellum would then mean a small fort or fortified place which was often used to describe watchtowers, outposts, or minor fortifications during the Roman Empire.

Evolution into English:

The Latin castellum passed into Old English as castel, but it was primarily reintroduced into English through, Old French, Castel or chastel (modern French: château) during the Norman Conquest (1066 CE), which had a profound impact on the English language.

Whereas, in Middle English, the word became castel, retaining the meaning of a large fortified residence or stronghold of a lord. However, in modern English, it was eventually standardized as "castle", the term came to refer specifically to the fortified residences of European nobility during the medieval period.