Nick Tingley writes his latest article for the site on a fascinating topic. He postulates on what could have happened had the 1944 Normandy Landings against Nazi Germany taken place in 1943. As we shall see, things may well have not turned out as well as they did…

In a mid-spring morning in 1943, France was awash with blood. Like the brutal battle of Gallipoli in the First World War, Allied troops found themselves once again pinned down and being forced back into the sea by a well-trained army. These troops, under the command of US General George Patton, had barely been on the shores of Normandy for more than a week before the German war machine had finally kicked in to gear. Starting at Benouville in the east, German Panzer units were screaming across the coast of Normandy, cutting off the divisions that had already made their way inland. Those that managed to cling on to the coastline began to be evacuated but the German counter-attack was so swift that many were left to their fate. For the second time in the Second World War, the Allies had been kicked out of France.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied effort in Europe, was given little choice but to order the withdrawal of the rest of the invasion force. Soon after he accepted full responsibility for the failure and was fired. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who only a year before had quite happily dismissed Churchill’s plan to attack the “soft underbelly of Europe”, was now forced to admit that the British Prime Minister may have been right. Under immense pressure from a population that was already astonished by America’s “Germany First Policy”, Roosevelt was forced to withdraw his forces from Europe to face off with the Empire of Japan in the Pacific.

After a year of revelling in the presence of their strong, American allies, Britain once again found itself facing the Nazi threat – alone in the West.

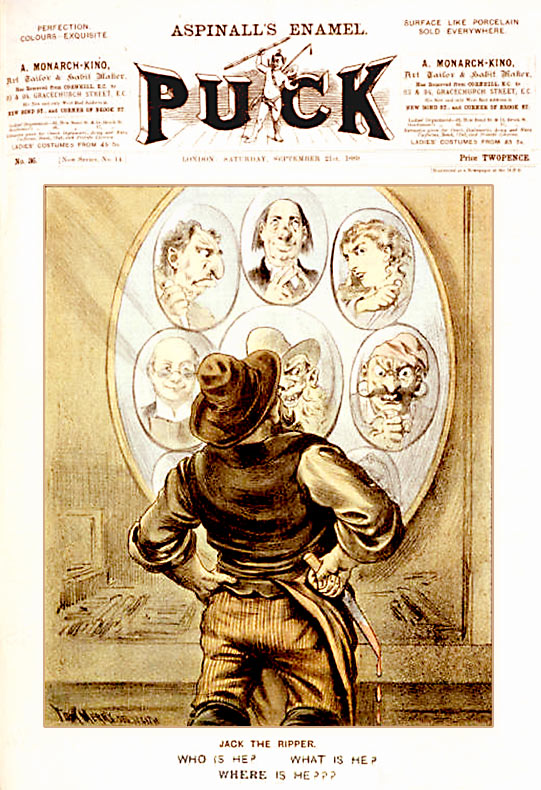

US troops before fighting began in June 1944.

Operation Round Up

But none of this happened.

The Allies did not launch a large-scale invasion of France in 1943. Nor did they fail to hold on to the landings when D-Day finally came about in 1944. Eisenhower was not fired and the American population did not demand that the Armed Forces withdraw to take on the more immediate Japanese threat.

But, when the Americans finally joined the war in Europe in 1942, this scenario of an attempted invasion of France in 1943 was certainly a real possibility. President Roosevelt and his generals, under a huge amount of pressure from the American people and his new Russian ally, Josef Stalin, were eager to open up a second front in France and bring the Nazis to heel as soon as possible.

The proposed invasion of France, codenamed “Operation Round Up”, was intended to take place in the spring of 1943. Its goal was to relieve pressure on the Soviet Union and force a quick end to what had already been a war to rival the Great War of 1914-18. The plan could have ended the war by Christmas 1943. But it was not to be.

The British Question

The main character responsible for delaying the invasion of France was the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. As a politician who had led Britain against the threat of invasion in 1940 and saw the turn about of the British fortunes of war in North Africa, Churchill held a lot of sway over both the British people and the American president. Whilst American generals were advocating an invasion of France as soon as the troops were ready to do so, Churchill and the British generals were suggesting a more roundabout way of dealing with the Nazi threat.

Churchill’s suggestion was simple. The Allies should focus on removing the Axis Powers from Africa first, to relieve pressure on the forces fighting from Egypt. Then, once Africa was secure, he later suggested that the Allies should attack Sicily and then mainland Italy in an attempt to knock the German’s closest ally, Italy, out of the war before taking the Nazis on in the final attack.

Unwilling to argue with the British, whose island offered the only close staging point for any invasion of France, Roosevelt eventually capitulated to Churchill’s plan, much to the dismay of his own generals. Seaborne landings took place in Africa in 1942 and in Sicily and Italy the following year.

Ever since, historians have been arguing over Churchill’s intentions for suggesting an attack on the “soft underbelly of Europe”. Many suggest that Churchill was only ever interested in securing Britain’s Empire by having troops in Africa and that the attack in Italy was designed so that Churchill could gain leverage against the Soviet Union in any potential post-war agreement. It appeared that many of the American generals at the time had considered this possibility as well. When Churchill further suggested the idea of an invasion of the Balkans prior to an invasion of France, the generals, and later historians, were quick to suggest that this was merely a ploy to ensure that the Soviet Union would have little bargaining power after the war was over. However, this invasion did not take place and Roosevelt finally stood his ground, insisting that the Allies’ next invasion should take place in France.

There are, however, some historians who have suggested that Churchill had learned from his experience at Gallipoli during the First World War and, as such, was proceeding with a greater caution when addressing the issue of defeating the Nazis. These historians are keen to point out that the sea and air landings in Africa, Sicily and Italy were by no means successful.

Learn By Experience

Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa, was a complete farce in comparison to the later D-Day landings. Both the British and Americans failed to achieve their objectives, the landings were delayed due to poor planning and an airborne operation with a single American parachute battalion turned into a complete nightmare. In the aftermath of Operation Torch, both the US General Patton and British General Clark acknowledged that the landings had been completely chaotic. They even went so far as to suggest that their troops would have been massacred had they been fighting German troops rather than the badly armed French colonial troops that they actually engaged.

Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, was little better. Although pre-dawn airborne drops and sea landings saw 80,000 allies land on in Sicily, the attacks themselves were often chaotic. After landing on shore, the US Seventh Army had no clear objectives due to the vague planning of the operation and it was only by the exploitative nature of General Patton that the army did not stop dead in its tracks. Furthermore, troops often came ashore in the wrong place and airborne troops found themselves scattered all over the place. The British glider force, who were tasked with capturing a key bridge south of Syracuse, lost the majority of its gliders to the sea and were forced to capture the bridge with only thirty men. To make matters worse, ground commanders often complained about the lack of Allied air cover over Sicily, but their air force colleagues were unwilling to risk fighters as they would often get picked off by their own anti-aircraft batteries.

The Allied landings in Italy in September 1943 appeared to be a drastic improvement on the earlier attempts in North Africa and Sicily, but this was largely due to the Italian government surrendering shortly afterwards. A later landing at Anzio in January 1944 failed to advance quickly enough and allowed the occupying Germans to fall back to more defensible positions.

Whilst many are quick to criticise Churchill for “leading the Allies up the Mediterranean path”, the chaotic invasions of North Africa, Sicily and Italy show us that the Allies were by no means ready to take on the Germans in 1943. In fact, many of the lessons learned from these failures during the earlier invasions ensured the success of Operation Overlord in June 1944. Regardless of Churchill’s reasoning, he had at least prevented a potentially disastrous invasion of France in 1943.

The What Could Have Beens

So what would have happened during a 1943 invasion of France?

There are many interpretations for what might have happened. I believe that General Patton would have been the obvious choice to lead the invasion of France. Patton was not chosen to lead the attack in 1944 due to an incident during the Sicily campaign where he slapped a soldier who was suffering from combat fatigue. But if the invasion of Sicily had never happened, this event may not have happened leaving Patton open to command the attack on the Normandy beaches.

There may still have been an attempt to attack and capture Pegasus Bridge, which was one of the few bridges that would allow the Germans access to attack the eastern flank of the Normandy beachheads. And this attack would probably have been undertaken by glider assault. But we can imagine that the attack would have been as successful as the glider assault in Sicily. With gliders crashing well short of the target there would have been few troops in position to hold the bridge. The troops at Pegasus Bridge would have easily been overrun and the Germans would have had the opportunity to cut the invading armies off from the sea.

There would have been an airborne assault, but given how chaotic the airborne assaults in North Africa and Sicily had been, the confusion that the paratroopers encountered on D-Day in 1944 would have been far greater in 1943 had they not had that earlier experience in the Mediterranean. The same can be said of the beach landings that would have been chaotic and delayed. We can quite easily imagine that the struggle that occurred on Omaha beach in 1944 would have been present and even greater at every single landing site in 1943.

Whilst we can’t know for sure that a 1943 invasion of France would have been a disaster, history suggests that it would have been. It is entirely possible that the landings themselves may have been a success, but without the experience of encountering those small failures in the otherwise successful landings in the Mediterranean it seems highly unlikely that the invasion of France would have achieved anything close to the success of D-Day. At best, an Allied Army would have found itself penned into the Normandy region by a more experienced German force. At worse, the Germans would have poured along the coast, cutting off the invasion forces and driving the rest back in to the sea.

Did you find this article interesting? If so, tell the world. Tweet about it , like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below...

References

The Second World War - Anthony Beevor (2012)

Invaders: British and American Experience of Seaborne Landings 1939 - 1945 - Colin John Bruce (1999)

Fighting them on the Beaches: The D-Day landings, June 6, 1944 - Nigel Cawthorne (2002)

D-Day Fails: Atomic Alternatives in Europe - Stephen Ambrose (1999)