Texan independence was. Significant issue in the 19th century. Here, Fredrick Wolf looks at how it was impacted by sovereignty and slavery. He also considers the role of the Alamo.

The Fall of the Alamo (1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk.

“…the institution of slavery is neither an interest to be defended nor an outrage to be denounced, but merely a bygone state of things, through which – as through many another unfortunate conditions of society – the evolution of the human race has carried it; and we can therefore devote ourselves to the investigation of the subject with no prejudice except in favor of historic truth.”

– Professor Justin H. Smith, The Annexation of Texas

The poster for the movie, The Alamo (1960), celebrates its history with the line, "The Mission That Became a Fortress…The Fortress That Became A Shrine….” The latter is a concise and accurate summary of the story of the structure, but not necessarily the events involved in what has famously become known as -- the Alamo – in downtown San Antonio, Texas.

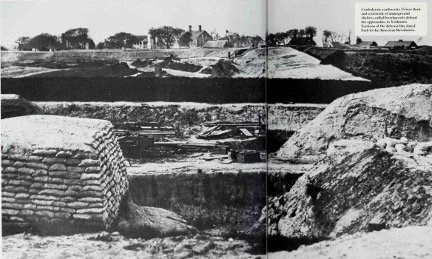

Some historians believe slavery was the driving issue in the battle at the Alamo, arguing that Mexico’s attempts to end slavery contrasted with the hopes of many white settlers in Texas at the time who moved to the region to farm cotton. Renovations to the Alamo, itself, have recently been stalled due to political issues and discussions over the site’s legacy including the role of slavery in the Texas revolution.”

The rebellion in the northern states of Mexico, historically, has been attributed to a response to President Antonio López de Santa Anna repealing Mexico’s Constitution of 1824, abolishing the state governments and issuing autocratic decrees including the suspension of individual property rights.

This work takes the position of the aforementioned Professor Smith: It argues neither for nor against the institution of slavery being the premise behind the battle of the Alamo. It merely develops a reasoned structure of the era detailing the events, circumstances and status of slavery in Mexico from the first Texas colonization contracts to the Texas Revolution. The reader may then draw his or her own conclusion regarding slavery being a motivating cause behind the siege of the Alamo and the struggle for Texas’s Independence from Mexico.

Settlers in Tejas

When Moses Austin secured his first empresario contract to transport settlers to territory now known as Texas, the territory was the possession of Spain, and slavery was legal under Spanish law. The initial contract of 1821 made with the Spanish government made it clear that property rights of future colonists would be protected, including their right to hold slaves.

Agustín de Iturbide, a Mexican caudillo (military chieftain), became the leader of the conservative faction in the Mexican independence movement against Spain; as Agustín I, he briefly became the first emperor of Mexico. The Iturbide government, of newly independent Mexico, reaffirmed in 1823 Moses Austin’s contract, with son, Stephen F. Austin as his lawful heir. This action secured the legal acquiescence of the Mexican national government to permit colonists and their slaves into the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas).

Issue of Slavery

The new Mexican Constitution of 1824 was vague on the issue of slavery, leaving the question to the individual states to determine how slavery would be dealt with. The law declared, generally, that Mexico would prohibit the importation of slaves, reflecting Mexico’s shift away from Spanish policies after gaining independence from Spain. But because the document left the issue of slavery to the states to decide, it was interpreted by Mexican legal authorities as only prohibiting the importation of slaves for resale. As a result, colonists in Texas, as well as native Mexican planters in southern Mexico, continued to import slaves for their own domestic use with the federal government making no effort to contravene such activity.

Coahuila y Tejas

The state of Coahuila y Tejas, officially the Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila y Tejas, was one of the constituent states of the newly established United Mexican States under its 1824 Constitution. The newly adopted state constitution of the state of Coahuila y Tejas allowed in 1827 for the importation of slaves from the U.S. for a period not to exceed six months after the document’s ratification. In September of that year, slaves could no longer be brought into Texas.

In May of 1828, the Congress of Coahuila y Tejas passed a law which made contracts of indentured servitude initiated in foreign countries valid within the state. This provided a means through which slaves could be brought into Texas by making them indentured servants for life. It should be noted that the distaste for slavery of many Mexican citizens and politicians was not necessarily due to a principled stand against the idea of slavery per se. It was, rather, the hereditary nature of slavery which was abhorrent to them. This law merely brought black servitude in Texas in line with the already existing form of servitude – the Mexican norm of debt peonage.

Slavery in Mexico

A legislative attempt to proscribe slavery within the country failed in the Mexican Congress in 1829. President Vicente Guerrero, second President of Mexico, and born of parents of African Mexican and Indian descent was granted sweeping powers to thwart Spain’s attempt to retake the country.

Jose Maria Tornel, the equivalent of the U.S. Speaker of the House of Representatives, influenced President Guerrero to use his newly granted emergency powers to abolish slavery in Mexico. But a little over two months later, the Governor of Coahuila y Tejas, Jose Maria Viesca, convinced the president to exempt Texas from the proscription. To be fair, it should be noted that even if the ban had taken effect in Texas, it would not have freed those already held under indentured servitude contracts.

Yet, at the time, events were changing rapidly in Mexico. In 1831, roughly eighteen months after Guerrero issued his decree banning slavery, it was annulled by the National Congress, along with most of the short-termed, late president’s emergency decrees. Slavery – involuntary servitude -- was once again the law of the land in all of Mexico. And it remained so until 1837, when the National Congress acted again, this time passing an emancipation bill – banning slavery -- nearly a year after Texas in 1836 had won its independence.

Debt Peonage

A few months after the National Congress had annulled Guerrero’s ban on slavery the state legislature of Coahuila y Tejas acted to limit indentured servitude contracts to ten years. But this did little to benefit those living under existing contracts; they still accumulated debt for food, clothing, housing, and medical care. The debt accrued such that it could never be satisfied and those under the contracts remained in debt to the holders of the contract – essentially -- in perpetuity.

This circumstance converted those under contract into debt peons at the end of their indenture terms. In other words, they were required to remain in service to the holders of the contract until those debts were paid, an eventuation nearly impossible. This was the system of servitude that was practiced throughout Mexico before and after Texas won its independence. It was not atypical for wealthy Mexican landowners to have thousands of debt peons in their service. And their treatment was much the same as slaves on American plantations. It should also be noted that the children of debt peons also accrued debts for their care while they were minors, making peonage functionally hereditary.

Such was the state of African bondage in Texas until independence was declared in 1836. The Texas Declaration of Independence, which lists all grievances set before the Mexican government, fails to mention slavery as a basis for redress.

Did Santa Anna march north to free the slaves, as one U.T. history professor has recently said? Or, was his intention to put down Federalist resistance in the northern Mexican states, of which Coahuila y Tejas was but one?

When Texas settlers rebelled in 1835, Santa Anna was quick to organize an expedition against them in defense of centralism. Texan colonists wanted to uphold federalism, a system that allowed for state sovereignty – freedom of choice. Santa Anna and several other Mexican politicians at the time advocated that a centralist government would better serve to unify their nation, after years of instability under federalism. A centralized authority, of course, could also sustain national privileges for the church and military, two special-interest groups that supported Santa Anna’s government.

As a parting remark, one point should be admitted into this commentary. The majority of Texas slaveholders were members of the Peace Party, an organization which lobbied against independence, at least until Mexican President Santa Anna made clear his intention to subdue them, by any means necessary, along with those of his perceived adversary -- the War Party.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

References

Costeloe, Michael. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835-1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Fowler, Will. “Santa Anna and His Legacy.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Latin American History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press USA, 2015.

Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Torget, Andrew J. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850. University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Smith, Justin H. The Annexation of Texas. New York, NY: The Baker and Taylor Co., 1911.

Burrough, B. and Stanford, J. (2021, June 10). The Myth of Alamo Gets the History All Wrong. The Washington Post. The myth of Alamo gets the history all wrong - The Washington Post

Burrough, B. and Stanford, J. (2021, June 10). We’ve Been Telling the Alamo Story Wrong for Nearly 200 Years. Now It’s Time to Correct the Record. Time.com. It's Time to Correct the Myths About the Battle of Alamo | TIME

Hanna, J. (2025, October 24). The CEO of the Alamo's historic site has resigned after a top Texas Republican criticized her. Associated Press. https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/ceo-alamos-historic-resigned-top-221630063.html

Webner, R. (2021, May 10). Alamo renovation gets stuck over arguments about slavery. The Texas Tribune. Alamo renovation gets stuck over arguments about slavery - The Texas Tribune

Moses Austin’s Spanish Empresario Contract. Texapedia.info. https://texapedia.info/1821-empresario-contract/

Barker, E. (2020, July 30). The History of Colonization in Texas: From Moses Austin to the National Colonization Law. Texas State Historical Association. Mexican Colonization Laws

McKay, S. (1994, December 1). The Constitution of 1824: Coahuila and Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Constitution of Coahuila and Texas

Coahuila y Tejas: The Mexican State Before Texas Independence. Texapedia.info. Coahuila y Tejas: The Mexican State Before Texas Independence

Joel. (2025, February 6). Rise of Debt Peonage in Mexico. Far Outliers. Rise of Debt Peonage in Mexico | Far Outliers

Anna, T. (Fall 2002). The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President (review). Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. Johns Hopkins University Press. Project MUSE - The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President (review)

Blake, R. (2020, August 2). The Guerrero Decree: Abolishing Slavery in Mexico. Texas State Historical Association. Guerrero Decree

Mexico frees slaves. (2025, September 15). Texas State Historical Association. Texas History Lives Here | Texas State Historical Association

Indentured servitude. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indentured_servitude

Barker, E. Pohl, J. (2025, May 21). The Texas Revolution: Key Events and Impact. Texas State Historical Association. Texas Revolution

Santa Anna and the Texas Revolution. Santa Anna's Role in the Texas Revolution

Dyreson, J. (1995, December 1). The Peace Party in Texas: A Historical Overview. Texas State Historical Association. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/peace-party