The USS Panay Incident played a crucial role in the timeline of the United States' involvement in international affairs in the late 1930s as the world prepared for the Second World War. Yet today, most Americans have never heard of the incident. It is cited as both the first time American Naval ships had been sunk by enemy aircraft, as well as the first time US ships had been targeted since the conclusion of World War I.

Ryan Reidway explains.

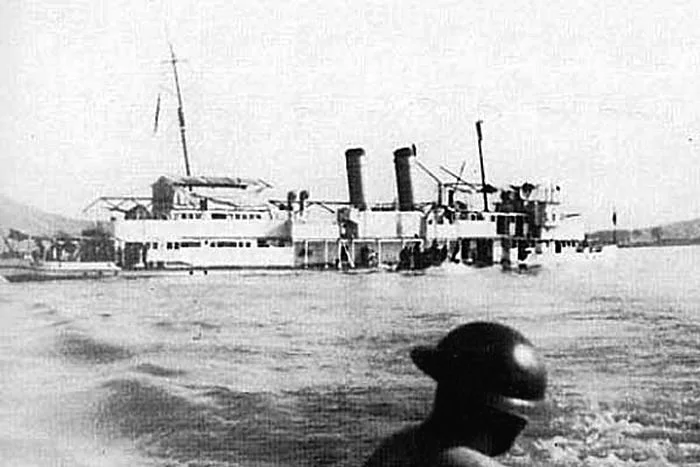

The USS Panay sinking after the Japanese attack.

With three men killed and 48 injured, the incident led, on one hand, to the passage of the March 1938 Naval Act that allowed the expansion of the American Pacific Fleet.[1] On the other hand, it led to increasing anti-war and isolationist sentiment at home. Happening only months after the adoption of the Ludlow Amendment, which restricted the ways Congress could declare war when attacks happened overseas[2]. Although there was initial condemnation and outrage towards the Japanese government in the United States, it seems to have been forgotten in the pages of history.

The USS Panay had been commissioned in 1927 in Shanghai as part of the Asiatic Fleet. It was designed to patrol the Yangtze River to protect American interests in China. It was a shallow draft river boat, with a displacement of between 370 and 500 tons. It could reach speeds of 13 knots and had armor plating on the forward and aft of the ship. It was armed with several.30 Caliber Lewis Machine Guns[3] as well as two 3-inch main guns[4]. Fon Huffman, who is believed to be the last living survivor of the Panay, proclaimed, “It was a good ship. It was a really good ship.”[5]

By the 1930s, the Panay and its crew had become accustomed to fending off pirates who often tried to attack Standard Oil vessels as they moved up and down the river. 1n 1931 According to Lieutenant Commander R. A. Dyer, "Firing on gunboats and merchant ships have [sic] become so routine that any vessel traversing the Yangtze River sails with the expectation of being fired upon. Fortunately," he added, "the Chinese appear to be rather poor marksmen and the ship has, so far, not sustained any casualties in these engagements."[6]

1937

Fast forward to the summer of 1937, when the Japanese army invaded China, Western powers, including the United States, looked on with horror and dismay at the brutality of the conflict. After the fall of Shanghai in November of that same year, Japanese commanders set their sights on Nanjing. Fearing for the lives of their citizen, the United States initially ordered all Americans to enter an International Safe Zone that had been set up in the city. But by early December, Chinese Nationalists had abandoned the city, and the American government wanted its citizens out.

On December 9th, 1937, the Panay’s commanding officer was Lieutenant Commander James Joseph Hughes, and its Executive Officer was Lieutenant Arthur F. Anders, received orders to evacuate all American Citizens from Nanjing. By that night, 15 American citizens, embassy workers, several foreign nationals, and reporters had boarded and joined the 59 officers and enlisted men already on the ship. The Panay remained anchored at the dock on December 10th, despite the carnage of the Japanese onslaught in the city.

By December 11th, Japanese artillery shells were landing too close for comfort, and the order to pull away from the dock was given. The ship slipped away from the dock with American flags flying visibly and proceeded to head up the Yangtze River. It joined a convoy of three Standard Oil ships, the Meiping, Meian, and Meihsia. Those ships had been helping to evacuate employees of Standard Oil, many of whom were Chinese.[7]

Early on December 12th, the Japanese naval officers boarded the ship for an inspection. Commander Hughes replied to the officers, “The United States is friendly to Japan and China alike. We do not give military information to either side.” [8]The Japanese officers left, and the Panay continued down river, eventually anchoring 28 miles north of Nanjing.[9]

Attack

Later that afternoon, as lunch was being served, three Japanese bombers bombed the Panay. After releasing their bombs, they came back around and strafed the ship with their machine guns. Battle stations were manned, and the crew of the Panay attempted to fight back. It was in vain as the ship had sustained too much damage, and the order to abandon ship was given. By 3:55 pm, the ship had sunk. Many of the wounded were evacuated from the ship via sampans as there were no lifeboats. As the men tried to escape the carnage, the Japanese planes came back and strafed them again.

When it was all over, three people had been killed and 50 had been wounded[10]. Two of the three oil tankers had sunk, and one had run aground. Desperate to avoid capture by the Japanese forces, the survivors of the Panay proceeded to walk towards the friendly Chinese village of Hoshien. They were later rescued by American and British naval vessels in the area.

Probably the most remarkable thing about the whole incident was that it was recorded. There were a few reporters aboard the ship, including Norman Alley of Universal Press. Remarkably, using his camera, he was able to document the entire event. The footage would later go on to be used in legal hearings between the governments of the United States and Japan, as well as be broadcast in movie theaters around the United States. A copy of the footage can still be found on the Internet Archive site. In it, there is a narration of the events of that day, including the moments before the attack, the call to arms, the heroic stand, and eventually the sinking of the ship. Viewers will also notice the very visible American flag, which would play a crucial role in the doubts historians have about the official narrative.

Apology

The Japanese government quickly issued a statement apologizing for the incident and claiming it was an unfortunate mistake. While there was an investigation conducted by the American Government, the results showed that the attack was due to “poor field communications and bad visibility”[11]. Ultimately, Japan paid over two million dollars in damages, and while the United States formally accepted the apology in 1938, the American public was outraged. Fear that the American people would demand war forced the United States government to bury the incident and continue diplomatic relations with the Japanese.

Historians have argued, however, that the pilots of the Japanese bombers would have known what the ship looked like, its position in the river, and would have seen the American Flags flying from the air. In addition, reports later came out that the Japanese military had ordered all ships sailing north on the Yangtze to be destroyed to target Chinese military forces. Documents also show that commanders of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy argued which branch was ultimately responsible. The last piece of evidence to show the Japanese involvement was the pilot's request for confirmation of permission to attack before bombing the Panay.

Regardless of the reason for the attack, it is surprising in the 21st Century that this kind of incident did not lead to conflict between the nations. Nonetheless, this tragic event has been forgotten by most despite its revealing nature of the state of events during the run-up to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Speculation dictates that the events of the Second World War could have been very different if the American government had pushed the issue.

Did you find that piece interesting? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

References

Alley, N. (Director). (n.d.). Norman Alley's Bombing of USS Panay Special Issue, 1937/12/12 [Film]. Universal Studios. https://archive.org/details/1937-12-12_Bombing_of_USS_Panay (Original work published 1937)

Barnett, K. (2016, 06 27). Fon Huffman Remembers the USS Panay Attack 1937. Ken Barnett Design Youtube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1yUbW_WkDM&list=PLtJturmrhWAHvT9Hoi9Z4r_vkvacS0Fx6&t=75s

Frank, L. (2023, 08 08). Hidden History: The USS "Panay" Incident. Daily Kos. https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2023/8/8/2172658/-Hidden-History-The-USS-Panay-Incident

HISTORY.com Editors. (2009, 11 09). Rape of Nanjing: Massacre, Facts & Aftermath | HISTORY. History.com. https://www.history.com/articles/nanjing-massacre

Lyons, C. (2015). Attack on the USS Panay. Warfare History Network. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/attack-on-the-uss-panay/

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2021, June 14). The Panay Incident. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved June 29, 2025, from https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1941/prelude/panay-incident.html

1937 USS Panay Incident | A Pearl Harbor Preview. (2024, 12). Today's History YouTube Channel. https://youtu.be/EKECgwufjg8?si=kqf-dnGCphliy0hv

Roberts Jr, F. N. (2012, 11). Climax of Isolationism, Countdown to World War. U.S. Naval Institute, 26(6). https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2012/november/climax-isolationism-countdown-world-war#:~:text=What%20became%20known%20as%20the%20Panay%20Incident%2C%20in,at%20home%20was%20strong%20and%20tensions%20abroad%20high.

USS Panay (PR-5). (n.d.). Detail Pedia. https://www.detailedpedia.com/wiki-USS_Panay_(PR-5)

[1] (Naval History and Heritage Command, 2021)

[2] (Roberts Jr, 2012,)

[3] (Naval History and Heritage Command, 2021)

[4] (Frank, 2023)

[5] (Barnett, 2016)

[6] (USS Panay (PR-5), n.d.)

[7] (Lyons, 2015)

[8] (Lyons, 2015)

[9] (Lyons, 2015)

[10] (Lyons, 2015)

[11] (Roberts Jr, 2012)