The Battle of the Allia and the subsequent sacking of Rome in 390 BCE (or 387 BCE, according to some sources) remain among the most traumatic events in early Roman history. Rome's humiliating defeat at the hands of the Gallic Senones, led by Brennus, exposed its military weaknesses and left a lasting psychological and strategic imprint on the Republic. The aftermath forced Rome to reassess its military doctrines and city defenses, setting in motion changes that would ultimately contribute to its rise as a dominant power in the Mediterranean world.

Terry Bailey explains.

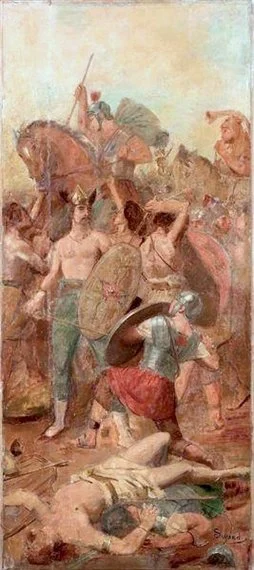

The Battle of the Allia by Gustave Surand.

The road to battle

In the early 4th century BCE, Rome was a rising power in central Italy, exerting influence over neighboring Latin and Etruscan states. However, the peninsula was not isolated from broader European movements. Around this time, waves of Celtic tribes, collectively referred to as Gauls, began moving southward, seeking fertile lands and opportunities for plunder.

The Senones, a Gallic tribe from modern-day France, moved into northern Italy and established themselves in the Po Valley. Their leader, Brennus, led them further south, eventually arriving at Clusium, an Etruscan city that sought Roman assistance against the invaders. Rome's intervention, however, escalated the situation. Roman envoys, instead of merely negotiating, participated in a skirmish against the Gauls, violating diplomatic protocols. Enraged, Brennus redirected his forces toward Rome itself, seeing it as a direct challenge.

The Battle of the Allia

The Romans, alarmed by the swift approach of the Gauls, hastily assembled a force to meet them at the River Allia, approximately 18 kilometers north of Rome. Though the exact size of the Roman force is unclear, contemporary accounts suggest it was poorly organized and inadequately prepared for the encounter. The Gallic army, on the other hand, was highly mobile, aggressive, and battle-hardened from their campaigns in northern regions.

The battle was a disaster for Rome. The Roman army, composed largely of levied citizen-soldiers, was unfamiliar with the Gauls' style of warfare. When the Gallic warriors charged, their sheer ferocity overwhelmed the Roman lines. The Roman left flank, where inexperienced troops were positioned, collapsed almost immediately. Panic spread through the ranks, leading to a chaotic retreat. Some Romans fled to Veii, while others scattered across the countryside. Those who sought refuge in Rome had little time to organize a meaningful defense before Brennus and his warriors arrived at the city's gates.

The sacking of Rome

With no standing army to oppose them, the Gauls entered Rome unchallenged. Most of the population had already fled, while the Senate and a small garrison took refuge atop the Capitoline Hill. The Gauls looted the city, slaughtering those who remained. Fire and destruction followed as buildings were razed and sacred sites desecrated.

For months, the defenders on the Capitoline resisted the siege. According to legend, the sacred geese of Juno warned them of a surprise Gaulic attack, allowing them to repel an attempted night assault. However, the Romans were in dire straits, suffering from starvation and dwindling morale. Eventually, a ransom was negotiated: Rome would be spared in exchange for 1,000 pounds of gold. When Romans protested the unfair weight of the scales used in the transaction, Brennus is said to have thrown his sword onto the scales, uttering the infamous words, "Vae victis"—"Woe to the vanquished."

The aftermath and long-term consequences

Though Rome survived the catastrophe, the scars of the sack lingered for generations, the event left several enduring impacts. The vulnerability of Rome during the Gallic invasion underscored the need for better defenses. This led to the construction of the Servian Wall, a massive fortification that protected the city from future incursions.

Rome learned hard lessons from the battle. The traditional levy-based military system proved inadequate against highly mobile and aggressive foes. Over time, Rome restructured its legions, improving discipline, training, and organization, changes that would eventually make it one of the most formidable military powers in history.

Roman psychology and national identity

The humiliation of the sacking became ingrained in Roman consciousness. It fostered a deep-seated fear and hatred of the Gauls, influencing Rome's later military campaigns against Celtic tribes. This trauma also strengthened Roman unity and determination, reinforcing the idea that Rome must never again allow itself to be so vulnerable.

Expansionist policies

Some historians argue that the sack of Rome instilled a more aggressive expansionist mindset in Roman leadership. Over the following centuries, Rome sought to secure its borders and assert dominance over the region and beyond, ensuring that it would never again be subjected to foreign invasion.

The aggressive expansionist policy transformed Rome into a dominant power and eventually into the undisputed master of the Mediterranean world. This period saw Rome engage in a series of wars that systematically dismantled its rivals and expanded its territorial control across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. The expansion was driven by a combination of strategic necessity, economic interests, military ambition, and the Roman Republic's political structure, which incentivized conquest through personal and national prestige, especially as Rome began to recover from the sacking of Rome.

One of the key aspects of this expansionist period was the series of wars against major Hellenistic kingdoms. The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BCE) marked Rome's direct intervention in Greek affairs, ending with the defeat of Philip V of Macedon at the Battle of Cynoscephalae.

Rome then positioned itself as the liberator of Greece, but this claim was soon undermined when it fought and defeated the Seleucid Empire in the Roman–Seleucid War (192–188 BCE), forcing King Antiochus III to withdraw from Asia Minor. Further wars followed, culminating in the destruction of Macedonian independence after the Third (171–168 BCE) and Fourth Macedonian Wars (150–148 BCE), and the eventual annexation of Greece following the sack of Corinth in 146 BCE.

Simultaneously, Rome expanded westward through its conflicts with Carthage. The Third Punic War (149–146 BCE) ended with the destruction of Carthage, securing Roman dominance in North Africa. In Spain, Rome waged prolonged campaigns against the Celtiberians, culminating in the conquest of Numantia in 133 BCE.

This relentless push for expansion continued in the late Republic with the annexation of Gaul under Julius Caesar (58–50 BCE) and further incursions into the eastern Mediterranean, including the absorption of Ptolemaic Egypt following Cleopatra's defeat in 31 BCE. By the time Augustus established the Principate, Rome had transformed from a republic controlling what is now Italy into a vast empire stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia, an expansion largely fueled by military prowess and a relentless pursuit of hegemony, in addition to fear of the defeat at the battle of Allia

A cautionary tale for the Ancient World

The sack of Rome was not just a Roman tragedy; it sent ripples throughout the known world. Other states and city-states took note of Rome's recovery, and as Rome grew stronger, it eventually turned the tables on those who had once threatened it. When Julius Caesar later campaigned against the Gauls in the 1st century BCE, he did so with an understanding of Rome's historical grievances.

In conclusion, the Battle of the Allia and the subsequent sack of Rome were among the darkest moments in early Roman history, yet they played a crucial role in shaping the Republic's destiny. Rather than breaking Rome, the trauma reinforced its resilience, prompting military, political, and psychological transformations that laid the foundation for its future supremacy. The lessons Rome learned from this defeat would ultimately propel it toward becoming one of the ancient world's greatest empires, ensuring that never again would the phrase "Vae victis" apply to the Eternal City.

The Battle of the Allia and the subsequent sack of Rome marked a profound turning point in the city's early history. What initially appeared to be a devastating and humiliating defeat ultimately became a catalyst for Rome's transformation into a formidable power. The shock of the Gallic invasion instilled in Rome a lasting fear of foreign incursions, driving fundamental changes in military organization, urban defense, and political strategy. The construction of the Servian Wall, the restructuring of Rome's military, and the psychological scars left by the sacking all contributed to a more disciplined and expansionist Republic.

Far from being a fatal blow, the Gallic sack reinforced the Roman ethos of perseverance and adaptability. The Republic's relentless drive to secure its borders and extend its influence stemmed in part from the trauma of 390 BCE, ensuring that Rome would never again be so vulnerable. Over the next centuries, this expansionist policy led Rome to dominate first the peninsula and then much of the Mediterranean world, systematically eliminating rival powers.

In retrospect, the sack of Rome was not just a crisis but a defining moment that shaped the Republic's destiny. It forged a national memory that inspired future generations of Romans, fueling their ambitions for conquest and solidifying their belief in Rome's manifest destiny. The phrase "Vae victis" may have once been a bitter reminder of defeat, but Rome's ultimate triumph ensured that it would never again be uttered at its expense. Instead, Rome would rise from the ashes of its sacking to build an empire that would stand as one of history's most enduring civilizations.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Notes:

The Senones

The Senones were one of the prominent Celtic tribes in ancient Gaul, inhabiting the region that roughly corresponds to modern-day northeastern France, particularly around the area of the Champagne and Burgundy regions. Their name, Senones, was used by the Romans, who encountered them during their expansion into Gaul. The Senones were part of a larger group of tribes known as the Gallic Senones and were renowned for their participation in major historical events, most notably their invasion of what is now known as Italy in the 4th century BCE.

In the early stages of their history, the Senones were a powerful and well-organized tribe, known for their martial prowess and distinct cultural practices. They were a part of the broader Celtic tradition, sharing similar customs and beliefs with other Gallic tribes. Their society was structured around a warrior elite, with chieftains and leaders who commanded respect through both martial skill and tribal allegiance. The Senones also maintained strong relationships with other Gallic tribes, particularly those in central Gaul, and participated in various alliances and conflicts.

The Senones' most notable historical moment came in 390 BCE, when they, along with other Gaulish tribes, famously sacked the city of Rome, as indicated in the main text. This event is often referred to as the Gallic Sack of Rome, during which the Senones, led by their chieftain Brennus, invaded the Peninsula and laid siege to Rome. The event marked a significant moment in Roman history, and while it did not result in long-term Gaulish dominance over Rome, it left an indelible mark on the Roman psyche, which would influence their later military strategies.

In terms of material culture, the Senones were skilled metalworkers, known for their intricately crafted weapons, armor, and jewelry. Archaeological evidence suggests that they lived in fortified hilltop settlements, known as oppida, which were typical of many Celtic tribes of the time. These settlements offered defense against both external enemies and internal conflicts. The Senones' religious practices involved a pantheon of Celtic gods and a strong reverence for the natural world, with sacred groves and ritual sites playing a central role in their spiritual life. Despite the eventual conquest of Gaul by the Romans, the cultural imprint of the Senones and their role in Gallic history remain an important part of ancient Celtic heritage.