It seems intuitive that if someone is firing bullets at you, you seek cover, and if no tree or rock or fence is available, to build something protective to hide behind. Yet, the U.S. Civil War was the first armed conflict in which extensive trenches were created. At the beginning, soldiers lined up and fired at those in the opposing line at point-blank range. But the death toll was outrageous; by the end of the war, picks and shovels became as much a part of fighting as artillery and guns.

Lloyd W Klein MD explains.

Entrenchments (also called field fortifications or earthworks) were widely used during the American Civil War, becoming increasingly important as the war progressed.. Trench warfare was not as prevalent as in later conflicts. Except for sieges of fortified cities, combat in the past had been of short duration, major battles rarely lasting for more than a day. Early in the Civil War, we don’t see entrenchments at places like Manassas, Shiloh, or Antietam. While fighting behind stone walls and other make-shift barriers was resorted to at various locations, such as Gettysburg, the concept of “digging in” wasn’t prevalent until much later. Nevertheless, the development of trench warfare tactics in the Civil War foreshadowed their extensive use in future conflicts.

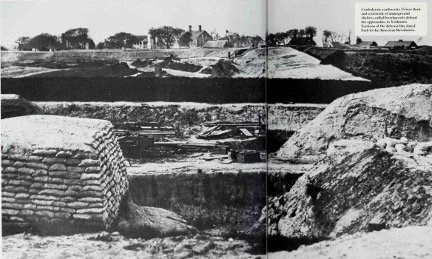

In discussing entrenchments, therefore, we are not talking about pre-existing stone walls (e.g., Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg) or terrain features (e.g., the Sunken Road at Antietam or Little Round Top at Gettysburg). A "trench" is a deep, long ditch dug into the ground to provide shelter for soldiers from enemy fire, while a "breastwork" is a temporary fortification typically made of earth, built up to chest height, allowing soldiers to fire over it while remaining partially protected from enemy fire; essentially, a breastwork is a more shallow, elevated defensive structure compared to a trench which is a deeper, dug-out ditch. Trenches are significantly deeper than breastworks, often allowing soldiers to stand upright within them. Trenches are dug into the ground, while breastworks are often built up from loose earth or sandbags, sometimes on top of a shallow ditch. While both offer protection, trenches generally provide better cover against heavy artillery and gunfire due to their depth.

Trench Construction

The construction of trenches during the Civil War was a labor-intensive process that required organization, manpower, and tools. Commanders would first decide on the location and layout of the trench system. This planning involved selecting high ground when possible, avoiding natural obstacles, and creating a network that provided defensive depth and coverage. Engineer officers would generally plan and supervise. Engineer regiments would assist, if available, but they were limited in number. Most of the work was performed by detailed infantry, perhaps assisted by black labor, free or enslaved, depending on which side.

Soldiers would begin digging the main trench line, typically starting with a shallow trench and gradually deepening it. The soil removed was piled up to create a parapet (a protective wall) in front of the trench to provide additional cover and protection.

Proper drainage was essential to prevent water from accumulating in the trenches. Soldiers would dig drainage ditches and sometimes line the trench floor with wooden planks (duckboards) to keep it dry and prevent mud.

Trenches were often camouflaged to blend in with the surrounding terrain and reduce their visibility to the enemy. Soldiers would use natural vegetation, earth, and other materials to disguise their positions.

“Saps" would be dug forward from an existing trench line, and the new trench extended laterally from there. In addition to the main front-line trenches, support trenches were dug behind the front lines to serve as secondary defensive positions, supply routes, and communication lines. These trenches were connected by communication trenches, which allowed safe movement of troops and supplies between different parts of the trench system..

A typical rifle trench or field fortification included several features.

· Parapet: The mound of earth in front, created from the soil dug from the trench. Protected soldiers from enemy fire.

· Firing step (banquette): A raised step inside the trench allowing soldiers to stand and fire over the parapet.

· Ditch: The trench itself, usually 4–6 feet deep and wide enough to allow movement.

· Revetments: Logs, planks, gabions (cylindrical baskets filled with dirt), or sod used to reinforce trench walls.

· Traverses: Earth barriers placed at intervals inside the trench to reduce the impact of enfilading fire.

Additional features of a sophisticated trench system might include:

· Bombproofs: Underground shelters made with logs and dirt to protect from artillery.

· Artillery platforms: Raised areas behind the main trench where cannons were mounted.

· Communication trenches: Smaller connecting trenches used to move troops and supplies safely.

The construction process was continuous, with soldiers constantly improving and expanding their trench networks to adapt to the evolving battlefield conditions. The resulting trench systems could become extensive and complex, providing significant defensive advantages in the static, attritional warfare that characterized the later stages of the Civil War.

The area surrounding Corinth, Mississippi, was fortified heavily by the Union and Confederate forces who struggled to control the strategically important town. Today, those earthworks are some of the best-preserved in the country. Halleck conceived of Corinth as a quasi-siege, and the concept of building ever-closer lines was a siege stratagem.

Fortifications were made from mounded soil, baskets, timber, and even bales of cotton were very effective. Earth and sod were the primary materials, because they absorbed bullets and shell fragments better than wood or stone. Gabions (wicker baskets filled with earth) were used to reinforce the trenches. To prevent the trench walls from collapsing, soldiers reinforced them with logs, planks, or other materials. In some cases, trenches were lined with sandbags or gabions to stabilize the walls and absorb enemy fire. Trenches were often supplemented with additional fortifications such as earthworks, redoubts (enclosed defensive structures), and gun emplacements. Obstacles like abatis (felled trees with sharpened branches), wire entanglements, and chevaux-de-frise (spiked barriers) were placed in front of the trenches to hinder enemy assaults.

A variety of tools were used to dig trenches, including shovels, picks, axes, spades, and occasionally makeshift tools. Soldiers themselves did the digging early on. Over time, both the Union and Confederate armies developed engineering units to supervise and speed up construction.

Increasing Utilization During the War

The underlying reasons for their increasing popularity as the war continued were improved technology, which had intensified firepower, and crippling deficiencies in communication, which technology had not yet solved. Field entrenchments were a response to progress in weapons technology. Rifle muskets, deadly accurate at several hundred yards, and close-order field artillery made previous battle tactics obsolete. The earthworks were designed to protect troops against this increased firepower. When McClellan advanced from Yorktown in the direction of Richmond, his progress was slowed by an outnumbered Confederate rearguard, which gave ground only grudgingly on a wide front. This was possible because no longer did men need to be packed into tight ranks in order to generate sufficient volume of fire to maintain their position against assault. Reciprocally, the thinning out of ranks made them less vulnerable to incoming fire. Such gams were ameliorated further when men took to lying down to shoot or, better still, made a point of firing from trenches or behind cover instead of standing up in the open, as in Napoleonic Wars or other European conflicts. As had been shown in the Crimea and at Solferino, head-on assaults against a well-emplaced enemy were no longer profitable operations of war. Even less viable was cavalry against modern artillery and rifle fire. Although neither army was yet able to apply the full devastating potential of modern weapons, and many old, muzzle-loading rifles were still in service, the Sharps and Spencer rifles were coming into use.

Early War Use (1861–1862)

At the beginning of the war, both Union and Confederate commanders favored offensive tactics and quick, decisive battles. There was a general belief that the war would be short, and both sides sought to achieve swift victories through aggressive maneuvers and direct engagements.

Many of the early commanders and soldiers lacked experience in modern warfare and did not initially appreciate the defensive advantages that entrenchments could provide. They were more accustomed to traditional Napoleonic tactics, which emphasized open-field battles and charges. Early in the war, entrenchments were used sparingly, mainly around forts, strategic river crossings, or defensive cities. The full impact of rifled muskets and artillery was not yet fully understood. As the war progressed, the increased range and accuracy of these weapons made entrenched positions more valuable for defense. Initially, commanders did not see the necessity for extensive fortifications.

At first, the strategic use of trenches was more limited and often makeshift. Trenches were used mainly for protection rather than extended combat. Building extensive entrenchments required significant time, labor, and resources. Early in the war, armies were more mobile and focused on quick movements and engagements rather than static defenses. There was also a psychological aspect to avoiding entrenchments. Many soldiers and commanders viewed digging in as a sign of weakness or lack of courage. They believed that bold offensive actions were more honorable and likely to bring victory.

However, battlefields like Yorktown (Peninsula Campaign, 1862) saw early use of extensive trenches by both Confederate and Union forces. When McClellan advanced from Yorktown in the direction of Richmond, his progress was slowed by an outnumbered Confederate rearguard, which gave ground only grudgingly on a wide front. This was possible because no longer did men need to be packed into tight ranks in order to generate sufficient volume of fire to maintain their position against assault. Reciprocally, the thinning out of ranks made them less vulnerable to incoming fire. Such gams were ameliorated further when men took to lying down to shoot or, better still, made a point of firing from trenches or behind cover instead of standing up in the open.

Battles like Antietam and Shiloh showed that lining up and firing wasn’t a winning tactic. As the war progressed and the brutal realities of modern warfare became apparent, the use of entrenchments increased significantly. The high casualties from direct assaults and the effectiveness of defensive positions in battles like Fredericksburg and Gettysburg led to a greater emphasis on fortifications. By the later stages of the war, trench warfare had become a common feature, culminating in the protracted sieges of Petersburg and other battles. By the end of the war, trench warfare had become the dominant mode of combat. The Union had some success with a new alignment of attacking forces at Spotsylvania Courthouse but in general, it became about how to deal with an entrenched enemy.

Shift to Entrenched Warfare (1863–1864)

Entrenchments became far more common as the war continued. Experience on many battlefields taught generals and soldiers that rifled muskets and artillery made frontal assaults deadly. The increased firepower and longer campaigns took their toll; armies began digging in to protect themselves during sieges or static operations. Increasingly, it was the best defensive strategy, especially for Rebel armies. Confederates, often outnumbered, used trenches to hold ground more effectively.

Key Examples of Entrenchments

Battle of Vicksburg (May-July 1863): The Siege of Vicksburg involved extensive entrenchments by both Union and Confederate forces. The Union Army, under General Ulysses S. Grant, besieged the city, and Confederate defenders used fortifications to hold off the attackers for over 40 days before surrendering. The fall of Vicksburg was a turning point in the war, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River.

Chattanooga (1863) – Confederates entrenched on Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge.

Overland Campaign (1864) –

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864) is another significant example where entrenchments played a crucial role. During this battle, which was part of the Overland Campaign, both Union and Confederate forces used extensive entrenchments. The most famous segment of the battle occurred at the "Bloody Angle," a section of the Confederate defensive works. At Spotsylvania, the unique earthworks straddled a ravine located on a hillside that ascends 12 feet over 30 yards. The defense was composed of three sets of trenches. The main line of trenches was composed of 11 steps with a traverse trench running along the side. The traverse trench connected all of the steps leading to the top of the hill. The other sets of trenches, just to the west of the main line, are constructed in the same fashion, but were significantly smaller than those along the mainline. Needless to say, this design was unlike any other fortifications in the Civil War.

Battle of Cold Harbor (May-June 1864): Confederate forces under General Lee were heavily entrenched, and Union forces led by General Grant suffered severe casualties in frontal assaults. The entrenched positions contributed to one of the war's most lopsided battles in terms of casualties. Union troops faced massive casualties assaulting well-dug Confederate lines.

Battle of Petersburg (June 1864-April 1865 – Perhaps the most significant use of trench warfare in the war. A 9-month siege with 30+ miles of trenches anticipated WWI-style warfare. Both sides built elaborate networks of trenches and fortifications. The Union forces, led by General Grant, eventually broke through the Confederate lines, leading to the fall of Richmond and the end of the war. Grant kept trying to swing around Lee's right and left flanks during the siege of Richmond and Petersburg. This eventually forced Lee to abandon his lines because he could not sufficiently man the ever-expanding defensive line that Grant imposed on him. Once dislodged, Grant turned Sheridan loose to cut off Lee's move west while the bulk of his army pushed in on Lee.

Petersburg

The most advanced form of trench warfare was observed in the Petersburg campaign in 1864. The defense of Petersburg by General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard is often regarded as both bold and brilliant. He counterattacked Grant’s forward forces periodically to delude the Union army into believing his thinly spread force was much stronger. Meanwhile, he had his engineers building trenches, so that after 3 days, he was able to fall back into a defendable position. One quick determined rush by a Corps on 15th June 1864 might well have broken through. I can never understand why a man of Beauregard’s genius could not find a more central role in the Confederate army.

By June 18th, the trenches were so sophisticated that an army of 65,000 was insufficient to overcome the 40,000 men Lee had rushed to the spot by rail. Faced at first by an improvised line, the initial Federal assault failed from lack of co-ordination. Detachments advanced independently, inadequately supported by artillery, and were pinned to the ground by fire of only moderate intensity. By the time a set-piece attack could be launched on the 18th, the volume of defensive fire was annihilating, compelling Grant to call a halt and commence probing the city’s southern flank with a view to isolating it.

Keeping pace with each Federal sidestep to their left, the Confederates extended their entrenchment to their right, always in time to meet each assault while fiercely contesting Grant’s further attempts to cut the railroad line to Richmond or the one running westward from Petersburg. Assault was usually of the battering-ram sort – a blasting of the selected point of attack by artillery and mortars (the latter, with their plunging fire, being particularly suitable for striking at the deeper enemy emplacements) followed by a massed infantry charge.

Petersburg is the first instance of the use by the Union Army of the rapid-fire gun, the important precursor to modern-day machine guns. Twelve of the guns were purchased personally by Union commanders. The Gatling gun was a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. The Gatling gun's operation centered on a cyclic multi-barrel design which featured multiple rotating barrels powered by a hand crank, capable of firing several hundred rounds per minute. This design facilitated cooling and synchronized the firing-reloading sequence. As the hand wheel was cranked, the barrels rotated, and each barrel sequentially loaded a single cartridge from a top mounted magazine, firing the shot when it reached a set position (usually at 4 o'clock), then ejects the spent casing out of the left side at the bottom, after which the barrel is empty and allowed to cool until rotated back to the top position and gravity-fed another new round. This configuration eliminated the need for a single reciprocating bolt design and allowed higher rates of fire to be achieved without the barrels overheating quickly.

The Dimmock Line

The Dimmock Line was a series of Confederate defensive earthworks constructed to protect Petersburg. It was named after Captain Charles H. Dimmock, a Confederate engineer who designed it in 1862. Its length was 10 miles, forming a semicircle around the eastern and southern approaches to Petersburg, and incorporated 55 numbered artillery redans (small forts) connected by infantry trenches with both flanks anchored on the Appomattox River. It was built by enslaved laborers and Confederate soldiers. The Dimmock Line was initially effective in delaying Union forces during the early days of the siege, but Grant’s forces eventually extended around the line. Union troops finally attacked Petersburg directly, and elements of the Dimmock Line fell in mid-June 1864, which began the Petersburg Campaign. The Dimmock Line is historically significant as one of the earliest large-scale uses of entrenched field defenses in modern warfare, showing the transition from open battle to static, fortified lines.

Battle of the Crater

Digging a tunnel under the trenches and blowing it up seems like the most obvious and simple thing in the world. One of the most notable examples is the Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg (July 30, 1864). The mine built under the Confederate Lines at the Battle of the Crater was anything but simple. Although Grant and Meade were aware of its construction, neither expected any tactical benefit and seemed to have lost interest in it.

The Attack at the Redoubt at Petersburg on July 30th is the “correct” name of what is known as the Battle of the Crater. A mine containing four tons of black powder was detonated beneath the redoubt and its defenders. Placed in a cross shaft at the end of a 511-foot tunnel that a regiment of coal miners secretly dug, it was blown at dawn without warning to the enemy. General Ambrose Burnside, whose four divisions of infantry were to exploit the explosion, seems to have relied too much upon the shock effect of the mine; beyond doubt, the measures he took to ensure that the troops not only occupied the crater but pressed on rapidly beyond were ambiguous and unambitious. As for the troops, so staggered were they by the enormity of the explosion, the air pressure of its blast and the scene of carnage which met their eyes when they poured into the crater, that they lost all sense of purpose and stayed there all morning, poking about among the grisly ruins of dismembered men and equipment.

Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants originated the concept, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's IX Corps, Pleasants, a mining engineer from Pennsylvania in civilian life, proposed digging a long mine shaft under the Confederate Army lines and planting explosive charges directly underneath a fort (Elliott's Salient) in the middle of the Confederate First Corps line. If successful, not only would all the defenders in the area be killed, but also a hole in the Confederate defenses would be opened. If enough Union troops filled the breach quickly enough and drove into the Confederate rear area, the Confederates would not be able to muster enough force to drive them out, and Petersburg might fall.

Union forces, under the command of General Ambrose Burnside, devised a plan to break the Confederate lines at Petersburg by digging a mine underneath the Confederate fortifications. A regiment of Pennsylvania coal miners was tasked with digging the tunnel, which extended over 500 feet to a point beneath the Confederate defenses. Burnside, whose reputation had suffered from his 1862 defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg and his poor performance earlier that year at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, was looking for a way to improve his military reputation.

The tunnel ran 510.8 feet. The shaft was dug with an upward incline to ensure water drainage. One-third of the way, the miners struck a vein of unworkable stone, so they further increased the slope to avoid it. Fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance. A canvas partition isolated the miners' air supply from outside air and allowed miners to enter and exit the work area easily. The miners had constructed a vertical exhaust shaft located well behind Union lines. At the vertical shaft's base, a fire was kept continuously burning. A wooden duct ran the entire length of the tunnel and protruded into the outside air. The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the chimney effect. The resulting vacuum then sucked fresh air in from the mine entrance via the wooden duct, which carried it down the length of the tunnel to the place in which the miners were working. That avoided the need for additional ventilation shafts, which could have been observed by the enemy, and it also easily disguised the diggers' progress.

Lee had intelligence of my construction but made no reaction for 2 weeks. Finally, he initiated some minimal attempts to identify its location, but never did. Shafts were sunk but never found.

The mine was “T” shaped. Its entrance was narrow and 50 feet below the Confederate line. At the end was a 75-foot perpendicular shaft into which the explosives were placed.

Union soldiers filled the mine with 320 kegs of black (gun) powder, totaling 8,000 pounds. The explosives were approximately 20 feet under the Confederate works, and the T-gap was packed shut with 11 feet of earth in the side galleries. A further 32 feet of packed earth was placed in the main gallery to prevent the explosion from blasting out the mouth of the mine.

The mine was detonated on the morning of July 30, 1864. The explosion created a massive crater, killing or wounding hundreds of Confederate soldiers and creating a breach in their lines. Despite the initial success of the explosion, the follow-up assault by Union troops was poorly executed. Confusion, miscommunication, and ineffective leadership led to a chaotic and ultimately failed attack. Confederate forces regrouped and launched counterattacks, inflicting heavy casualties on the Union troops who had entered the crater. The Union assault ended in disaster, and the Confederate lines held.

The reasons for the limited Use of mines included:

· Technical Challenges: Digging mines required specialized skills and knowledge, which were not always available in sufficient quantities. The process was labor-intensive and time-consuming, making it difficult to employ on a large scale.

· Strategic Focus: Early in the war, both sides focused on traditional offensive and defensive tactics rather than siege warfare. As the war progressed and trench warfare became more common, the use of mining techniques increased, but it never reached the scale seen in World War I.

· Resource Constraints: Mining operations required significant resources, including labor, explosives, and time. Both Union and Confederate forces often faced logistical challenges that limited their ability to conduct large-scale mining operations.

· Effectiveness: While mines could create breaches in enemy lines, the effectiveness of such tactics depended on the ability to exploit the breach quickly and effectively. As seen in the Battle of the Crater, poor execution of follow-up attacks could negate the initial success of the mine explosion.

Overall, while mines were used during the Civil War, their employment was limited by technical, logistical, and strategic factors. The Battle of the Crater stands out as a significant example of mining in the Civil War, highlighting both the potential and the challenges of this tactic.

Impact and Legacy

Entrenchments slowed campaigns, turning mobile warfare into grinding, attritional battles.

They foreshadowed trench warfare in World War I, especially the siege at Petersburg.

They reflected how military technology had advanced faster than tactics, forcing adaptation.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

Further Reading

· https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/trench-warfare

· http://www.petersburgproject.org/trench-warfare-in-civil-war-history.html

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/something-new-art-war-civil-war-earthworks-and-trenches

· https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2019/01/08/trench-warfare-in-the-american-civil-war/