During the presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981-89) the Cold War got hotter – and there were a number of major Cold War battlegrounds. Somebody who played a key role in many of these was CIA Director William Casey. Casey was to play a major role in several noteworthy and controversial events, perhaps most infamously in the Iran-Contra Affair. Scott Rose explains.

You can read Scott’s past articles about spies who shared American atomic secrets with the Soviet Union (read here), the 1950s “Red Scare” (read here), the American who supplied the Soviets with secrets in the 1980s (read here), and Cuban spies in the US in the 1980s (read here).

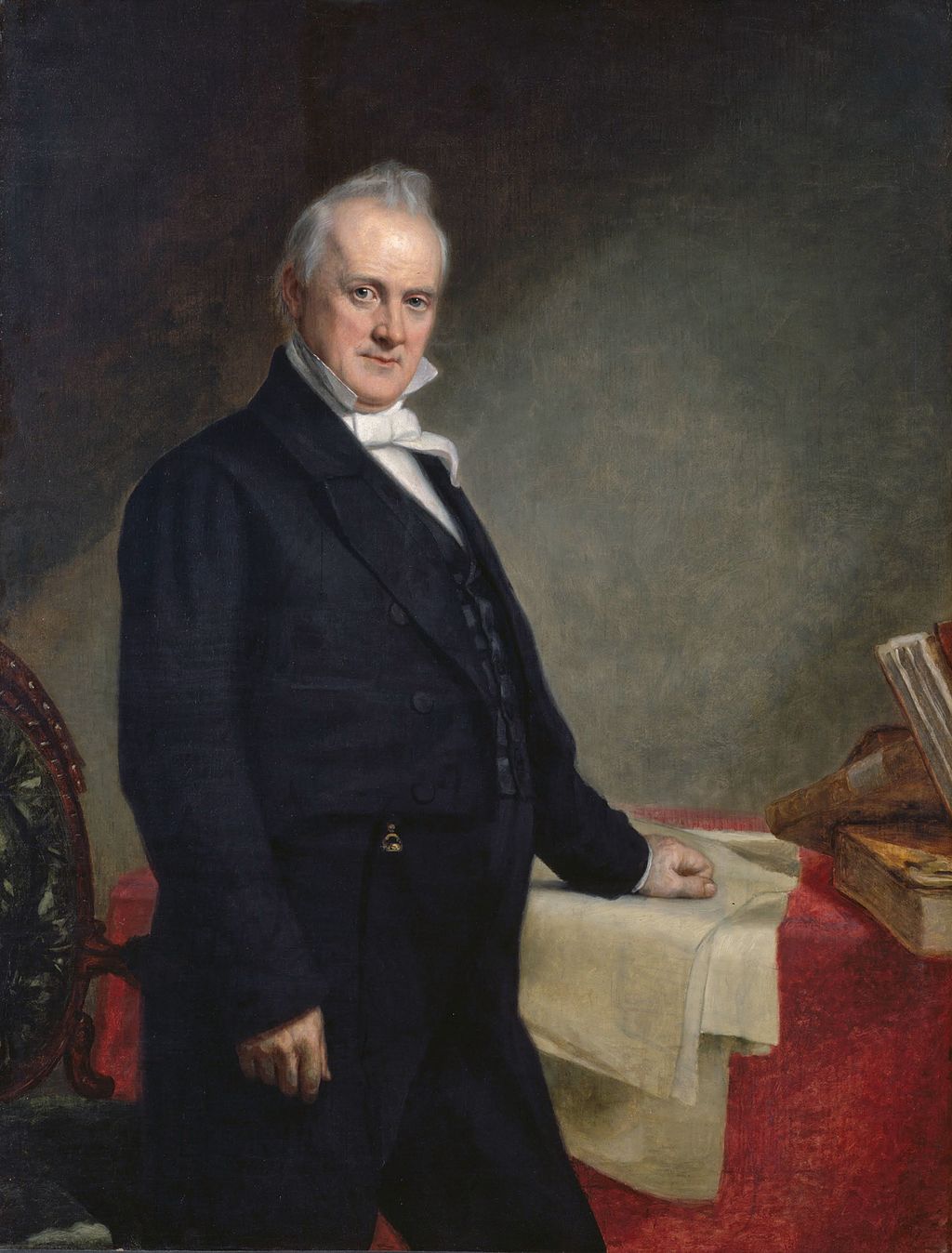

William Casey, CIA Director from 1981-1987.

As the Cold War drew to its conclusion, President Ronald Reagan was viewed as the one individual most responsible for the eventual demise of the Soviet Union. Reagan’s “Tear down this wall” speech at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin will probably always be thought of as the beginning of the end of communism in the U.S.S.R. and its satellite states.

However, there was another American official just as responsible for the Cold War victory of the Western world. William J. “Bill” Casey was Reagan’s CIA Director from 1981-1987, and Casey pulled the strings of American Cold War policy, making it his personal crusade to bleed the Soviet Union dry. Undoubtedly, Casey was one of the most powerful CIA Directors to ever hold the position.

Instead of being remembered for his patriotism as Reagan is, Casey’s legacy is quite controversial and unclear. Most Americans who remember Casey will forever associate him with the murky episode known as the Iran-Contra Affair.

Lawyer, Spymaster, Writer

Bill Casey was born in New York in 1913, to a hard-working family with limited financial means. From his childhood onward, Casey was ambitious and determined to change his social status. During his grade school years, he displayed great intellect, while showing a temperamental side as well, earning the nickname “Volcano” from his classmates. The only mark he ever received less than a B grade was a C in personal conduct. He became a caddie at a local golf course and taught himself how to play golf, which would remain a lifelong hobby.

Casey’s good grades got him into Fordham University in Manhattan, followed by law school at St. John’s University. In 1938, he passed the bar exam and began working at a law firm in New York. Casey displayed a talent in business and financial law, and created what is known as the “tax shelter.”

During World War II, Casey went to work for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the pre-cursor of the Central Intelligence Agency. He served in France and helped coordinate American spying operations inside Nazi Germany. Fiercely patriotic, Casey was by all accounts very effective in his position managing spies and gleaning vital information as the Allies prepared to invade Germany, and was awarded the Bronze Star for his service. After the war, he would return to his legal practice in New York.

Casey wrote several books about business law during the 1950s; the books sold well, and were widely purchased by other American lawyers. He made a small fortune, which was multiplied by successfully investing his earnings into a variety of business ventures and stock holdings. He also lectured on tax law for fourteen years at New York University.

Casey was a strong supporter of Richard Nixon during the election of 1968. Nixon and Casey had common ground; both were conservative lawyers, World War II veterans, and staunch anti-Communists. In 1971, Nixon named Casey chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and three years later, Casey became Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs.

A Partnership with Reagan

During the late 1970s, the United States looked to be losing prestige on the world stage. The Jimmy Carter Administration had failed to check Soviet influence around the world, and the Iran hostage crisis had made Carter appear soft. The American economy was in recession, compounding the nation’s problems in foreign affairs.

Ronald Reagan was challenging Carter in the 1980 election, vowing to restore America to its former glory. An unabashed capitalist and anti-Soviet, Reagan was a candidate Casey could relate to, just as Nixon had been. Upon announcing his candidacy, Reagan named the crafty and tireless Casey to be his campaign chairman. Reagan won in a landslide, and shortly after he was inaugurated, the Americans who had been held hostage in Iran were released. There has been a popular theory that Casey persuaded the Iranians to delay the release in order to weaken the Carter campaign; whether or not this was true has never been established.

Reagan asked Casey to become the new CIA Director, but initially Casey was not enthused about the prospect. He wanted to help shape American foreign policy, not merely report intelligence that had been gathered. However, Reagan promised Casey he would be given a large role in the country’s international affairs, and Casey took the job. Still well respected in the intelligence community for his OSS operations, he was a popular choice with many of the senior officials at the CIA.

During the Carter years, the CIA had been vilified in several Senate hearings. The Agency’s budget had been drastically cut, and by 1980 morale had dwindled. Upon becoming Director, Casey sought to rebuild the CIA back into the world’s strongest and most effective intelligence organization. Budgets were increased, and many new agents and administrators were hired. Casey voiced his intention to not only stop the increase of Soviet influence, but to “roll back” the Soviet world presence as well. His understanding of intelligence gathering and economics had put him in a unique position to do just that.

Taking on the Soviets

As the American economy recovered, Casey realized that the Soviet economic system could be damaged through long, drawn-out military operations such as the one in Afghanistan. The Soviets had invaded the country in 1979, but were now engaged in an ongoing conflict with Afghan rebels known as mujahedeen, or freedom-fighters. Casey asked Congress for financial aid for the Afghans, and received even more money than he had asked for. The CIA used these resources to furnish the Afghans with military equipment for use against the Soviets. Before long, the mujahedeenwere using American anti-aircraft missiles to bring down Soviet military helicopters. Just as Casey had expected, the U.S.S.R. poured more money and personnel into the conflict. In all, the Soviets would be bogged down in Afghanistan for nearly ten years, before withdrawing in 1989, losing billions of dollars and thousands of troops along the way.

Casey had hoped to accomplish the same objectives in Nicaragua, where the Soviets were sending $400 million per year to back the communist Sandinista government in its fight against the American-backed Contra forces. However, Congress was not as receptive to aiding the Contras, who had a less-than-stellar record when it came to human rights. Eventually, a bill was passed to limit American aid to the Contras. When the CIA mined harbors in Nicaragua, Casey was called to testify before Congress, and most of his answers were vague and indirect. By this time, Casey spoke in a slurring fashion (referring to Nicaragua as Nica-wag-wa), and there were many occasions when he spoke and left his listeners completely confused. In 1984, Congress passed a second measure, completely banning American aid to the Contras.

Neither Casey nor President Reagan had any intention of letting the Contra cause die. Before the second Congressional Bill was passed, Reagan asked his National Security Advisor, Robert McFarlane, to find a way to keep the Contras afloat. McFarlane and his deputy, Lt. Colonel Oliver North, were able to persuade the royal family of Saudi Arabia to send a million dollars per month to the Contras. This was a far cry from the level of assistance the Sandinistas were receiving from the Soviets, but enough to keep the war going for the foreseeable future. For Casey’s part, he went on record that the CIA no longer had any involvement in Nicaragua.

In 1984, Casey had another huge problem to deal with. William Buckley, the CIA station chief in Lebanon, had been kidnapped by Hezbollah, an Iranian-backed organization. Shortly after Buckley’s kidnapping, American intelligence operatives in Lebanon began to disappear. It was clear that Hezbollah was torturing Buckley to gain information. These fears were confirmed in early 1985 when a videotape arrived, showing Buckley being tortured. Reportedly, the tape was so graphic that several CIA officials openly wept upon watching it.

The Iran-Contra Conundrum

Casey ordered his subordinates to find Buckley’s location and plan a rescue mission. In spite of this, the CIA couldn’t determine where Buckley was, or if he was even still in Lebanon. With each passing day, the Agency became more desperate to find the agent.

Eventually, a shimmer of promise came in the form of an Israeli foreign agent named David Kimche. In July of 1985, Kimche visited Robert McFarlane in Washington, telling the National Security Advisor that there might be a way to get Buckley and six additional American hostages released. Kimche told McFarlane that there was a group of Iranians who wanted American support for overthrowing the anti-American Iranian government of Ayatollah Khomeini. In return, these Iranians would use their influence with Hezbollah to obtain the return of the Americans being held in Lebanon, including Buckley. The point of contact would be an Iranian named Manucher Ghorbanifar.

McFarlane told President Reagan and other cabinet members, including Casey, about his conversation with Kimche. The President and Casey were in full support, while others in the Administration were more suspicious of what they heard. Kimche returned in August, telling McFarlane that Ghorbanifar’s group was asking for American weapons as part of the deal. Secretary of State George Shultz and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger were opposed to the idea, arguing that it would become an “arms for hostages” situation. Undeterred, Kimche proposed to McFarlane that Israel sell the weapons to Ghorbanifar, with the United States resupplying Israel. Weinberger argued that this would be illegal, while Casey disagreed. McFarlane and Casey supported Kimche’s idea, and ultimately, so did President Reagan. However, Casey had not been forthcoming with the President or McFarlane; he was actually already aware of Manucher Ghorbanifar. The CIA had met with the Iranian in 1984, administering two polygraph tests which Ghorbanifar had failed. Afterward, the CIA issued a “burn notice” on Ghorbanifar, meaning he was not to be trusted under any circumstance, a fact Casey made no mention of.

Shortly afterward, the arms shipments began. However, after the first shipment of TOW missiles, Ghorbanifar claimed the shipment had “fallen into the wrong hands.” After the second shipment, Ghorbanifar told McFarlane that Hezbollah would release one hostage, and for McFarlane to pick the hostage. McFarlane promptly picked William Buckley, but to Casey’s horror, the captors replied that Buckley was too ill to be moved, and another hostage would have to be chosen. Within a few months, the American government would find out that Buckley had actually died of a heart attack while being tortured in June of 1985.

The arms shipments continued into 1986; in all, there were seven shipments, with only three hostages being released. Then, in autumn of 1986, the lid was blown off the entire operation. In October, a helicopter carrying supplies to the Contras was shot down in Nicaragua. The lone survivor, an American named Eugene Hasenfus, told the Sandinistas that he was a CIA operative, which Casey denied. Then, in November, a Lebanese magazine reported the arms shipments to Iran. The Reagan Administration initially refuted the allegations, promising an investigation. Later the same month, Attorney General Edwin Meese confirmed not only that the arms shipments had indeed occurred, but also that proceeds from the arms sales had been diverted to the Contras in Nicaragua.

The spotlight turned squarely on Casey and the CIA. He was called to testify before Congress in December; however, the morning before he would have testified, Casey suffered a seizure at CIA headquarters. Taken to the hospital, he suffered a second seizure the same day. He was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor, and three days later he had surgery to remove the tumor. Casey would never recover his health, and resigned as CIA Director in January of 1987.

As the Iran-Contra affair unfolded in spring of 1987, several current and former members of the Reagan Administration were called to testify before Congress, but Casey was never able to do so. Most of the American public speculated that Casey was the one person who knew the entire story. On May 5, a former Air Force officer and CIA operative named Richard Secord testified that he organized weapons deliveries to the Contras, under direction of Casey and Oliver North. The next day, Bill Casey passed away.

Legendary Washington Postreporter Bob Woodward wrote a book called Veilabout Casey and the CIA, which includes a controversial story about Casey during his final days. Whether the story is factual or simply sensationalism is up for debate. Woodward claimed to have entered Casey’s hospital room for a few minutes while Casey’s guards were away. According to Woodward, he asked Casey, “You knew about the diversion to the Contras didn’t you?” He claims Casey looked and him and nodded that indeed he had. Woodward also states that he then asked the former CIA Director why he had approved of the events that had taken place, to which Casey faintly replied, “I believed.”

What do you think of the Iran-Contra affair? Let us know below.

References

Steve Coll, Ghost Wars, Penguin Press, London, 2004

Robert C. McFarlane, Special Trust, Cadell & Davies, New York, 1994

Joseph E. Persico, Casey: The Lives and Secrets of William J. Casey: From The OSS to the CIA, Penguin Books, London, 1991

Bob Woodward, Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA 1981-1987, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1987