In 1953, following his July 26 assault on the Moncada Barracks in Oriente province, a young lawyer and the mastermind of the attack in which many Cubans perished, named Fidel Castro, appeared in court to face prosecution. Out of as much desperation as revolutionary zeal, he delivered a powerful, hours-long speech in his defense. As of yet, no record of this speech has been found, and Fidel Castro was unsuccessful in avoiding conviction.

Here, Logan M. Williams considers Castro’s speech and looks at the history, successes, and failures of pre-revolutionary Cuba.

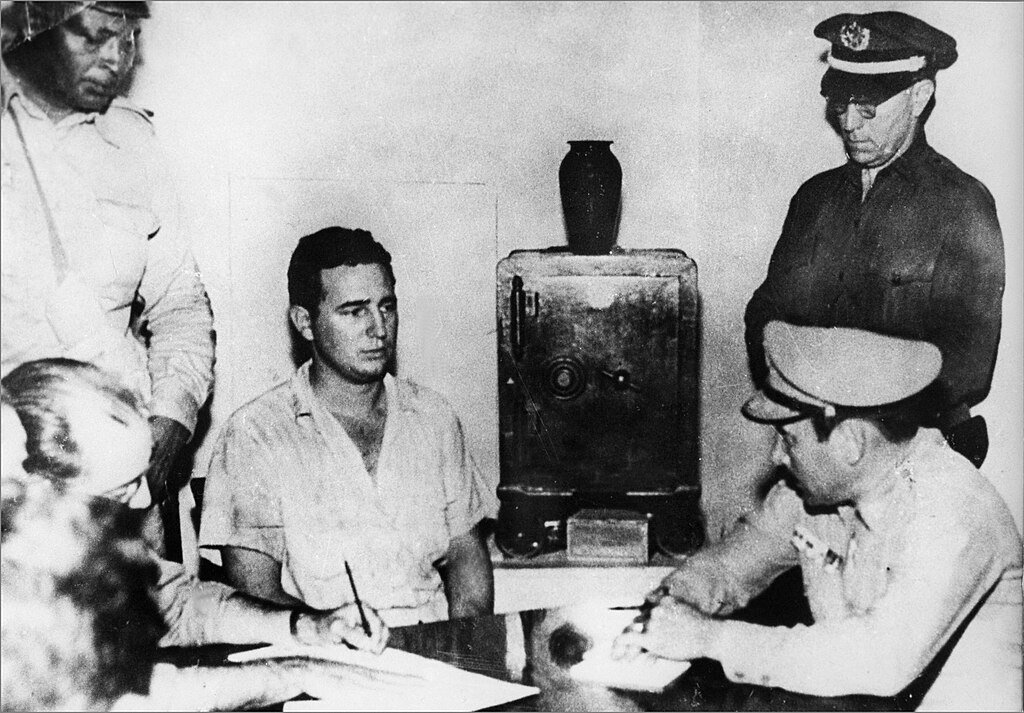

Fidel Castro under arrest after the 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks.

Castro was sentenced to a term of 15 years imprisonment, of which he only ended up serving less than three, in Cuba’s Presidio Modelo on the Isle of Pines. During his time in prison, he gave newspaper interviews, and continued to participate in the organizing of Cuba’s anti-Batista efforts. While in prison, he also spent a great deal of time reconstructing a “record” – used loosely, because it was not an exact copy or a true record, due to the fact that it contained several embellishments and added phrases – of the speech that he delivered in court on that fateful day. One of the embellishments which he added to the recreated speech is one of the most infamous political phrases of the modern era, and it would become the title of his work: “History Will Absolve Me." The phrase was eerily similar to one used by the German despot, Adolf Hitler, who said when he found himself in a situation much like Castro’s, that the judgement of the “eternal court of history” would exonerate him.

Castro’s recreated speech would eventually transform into a manifesto for his future revolutionary activities and become required reading for militant leftists around the world. In it, Castro expressed the belief that the desperate conditions under which some Cubans suffered, provided justification for the radical nature of his actions. Castro described these conditions as follows: “the people have neither homes nor electricity” and those who were lucky enough to have shelter “live cramped [with their families] into barracks and tenements without even the minimum sanitary requirements.” He stated that “rural children are consumed by parasites which filter through their bare feet from the earth” and that Cuba had “thousands of children who die every year from lack of [medical] facilities.” Castro attributed these social conditions to an indifferent society as well as a corrupt and negligent government. Indeed, denigration of the Cuban Republic period is still a mainstay of Cuban regime propaganda today, which sees this sort of fear-mongering as the only way to justify its increasingly repressive regime.

Pre-Revolutionary Cuba

This propaganda may be effective, as most of today’s world now knows the Cuban Republic of 1902-1959 by its reputation for troubling and potentially neo-colonial relations with the United States or as a period of crime, graft, moral decay, political unrest, and total misery (if they know anything at all). However, this isn’t a complete representation of the era, as Castro himself alluded to in his speech before the court. Of the Cuban Republic, before the inception of the Batista dictatorship in 1952, Castro stated:

“It had its constitution, its laws, its civil rights, a president, a Congress, and law courts. Everyone could assemble, associate, speak and write with complete freedom. The people were not satisfied with the government officials at that time, but [the people] had the power to elect new officials and only a few days remained before they were going to do so! There existed a public opinion both respected and heeded and all problems of common interest were freely discussed. There were political parties, radio and television debates and forums, and public meetings. The whole nation throbbed with enthusiasm.”

He also noted that “the [Cuban] people were proud of their love of liberty and they carried their heads high in the conviction that liberty would be respected as a sacred right.” Within today’s Cuba, Castro’s pamphlet, “History Will Absolve Me,” is not easily found in its entirety.

While certain aspects of Cuban society (particularly the government and political class) may have earned the harrowing reputation presented by Castroist propaganda, the lived experience of the average Cuban who resided on the island in this era – which was actually a period in which Cuba underwent a remarkable transformation and made steadfast progress towards liberal development – tells a vastly different story. Due to the work of a few committed scholars, who have dedicated their time to chronicling the achievements of the Cuban people, we have brought light to the Cuban “Dark Ages.”

Cuban Republic in History

Traditionally, the Cuban Republic is identified as the form of government which existed between the years 1902 and 1959, although this is not entirely accurate, and it doesn’t do justice to the efforts of Cuba’s liberals and independence fighters. The Cuban Republic came into existence for the first time during the second half of the nineteenth century, during the Ten Years War, when the island revolted against Spain. However, it ceased to exist following the defeat of the Cuban separatists, and the complete reimposition of Spanish colonial rule. The Cuban Republic was revived during the Cuban War of Independence, and it experienced several early and remarkable successes in governance, whilst embroiled in a brutally destructive war with Spain. Horatio Rubens, a New York-based attorney who was a personal friend of Jose Martí and who served as a principal advisor to Martí’s Cuban Revolutionary Party as well as the U.S. provisional government during the brief occupation of the island, describes the accomplishments of this iteration of the Cuban Republic in an 1898 journal article for The North American Review. These revolutionaries, amid a war, had built a modern, representative government, based upon republican principles. This new government included a system for the collection of taxes, as well as significant checks and balances, especially upon military authority. In Eastern Cuba which, at this point, was largely poor as well as underdeveloped, and entirely in the control of the revolutionaries (except for major cities), newspapers were published frequently, which was a positive indicator for free speech as well as other democratic freedoms, and schools were even established. Most notably, the Cuban Republic experienced its first election in 1897, ostensibly free from the corruption and political violence which would plague future such elections.

After a brief period of initial occupation lasting from the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898 to 1902, the United States’ provisional government and most of its soldiers departed Cuba; the island nation had finally achieved a measure of autonomy (autonomy is used in this case to indicate the existence of a level of agency and self-government short of complete sovereignty). Most scholars of the Republic during this period in Cuban history stubbornly refuse to refer to it as sovereign Cuba, at least until the 1930s, due to the existence of the Platt Amendment, which formalized the continuation of U.S. dominance over Cuba by restricting the new island nation’s rights in the realm of international relations and by cementing the United States’ right to intervene militarily on the island under certain circumstances. Thus, Cuba’s sovereignty was so constrained until at least 1934, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” policy – and the persistence of Cuban diplomats – brought about the dismantling of the amendment.

The economy

After 1902, however, regardless of the existence of the Platt Amendment, the Cuban Republic was once again free to pursue liberalization and advancement in a Cuban manner. In spite of the many aforementioned plagues and hurdles faced by Cuba’s newly formed state, the Cuban Republic made extraordinary progress in the economic and social spheres; it was fully engaged in the crucible that is liberalization.

Economic data from this period indicate that the Cuban Republic was a middle-income (likely upper-middle income by modern standards) country, with living conditions comparable to some European countries, or to those in the southern United States (which were the poorest states in the U.S. at this time). Consumption rates at certain points during the Cuban Republic measured as high as 70% of most European economies and exceeded those of almost every other Latin American nation. The Cuban Republic’s income per capita before the Revolution of 1959, was well above the average for Latin America; in fact, it was equidistant from the European and Latin American averages. Several consumption-based economic indicators are especially useful in highlighting Cuba’s prosperity during the republican period, mainly those which relate to private ownership of technology and luxury items, as well as those which relate to food supply and nourishment. The Cuban Republic’s rate of private television ownership (measured by the number of televisions per 1000 persons) was nearly 7 times greater than the average for Latin American states, and approximately equal to the European average. Likewise, Cuban private ownership of radios was well above Latin America’s average, as was the rate of private ownership for passenger vehicles. Additionally, during the Cuban Republic period, Cuba regularly led Latin America in food production, as well as per capita daily caloric consumption; whereas, Cuba following the Revolution of 1959 has often lagged behind other Latin American nations in these regards. Finally, the rapid development of Cuba during the Republic era is evident by the fact that for much of that time period, Cuba led Latin America as the region's largest consumer of cement, a resource which is essential for the construction of new infrastructure. Additionally, Cuba’s investment in technology and mechanization during this period drastically exceeded that of its neighbors. In 1920, a time known as the “Dance of Millions” due to its especially high levels of prosperity, Cuba’s investment in these goods accounted for a quarter of the total investment in machinery for the entirety of Latin America (more of a cultural conception than a geographic region, “Latin America” has ill-defined borders, but for context can be estimated as containing approximately between 20-30 different countries.) After presenting many of the above statistics, and in light of the decidedly positive, albeit one-sided, perspective that they offer, authors of the above-cited paper in the Journal of Economic History, Marriane Ward and John Devereux concluded that “The story of Cuba during the twentieth century is therefore the story of how it has fallen in the world income distribution…. Over the last fifty years, Cuba has replicated the failings of command economies elsewhere albeit in a uniquely Cuban fashion.”

Infrastructure

The Cuban Republic’s remarkable success wasn’t limited to solely economic factors, Cuba also made remarkable progress in improving its transportation infrastructure. This helped the Republic to extend the rule of law, as well as healthcare and education opportunities, into the Eastern (largely rural and poor) portion of the island. During the republican period, railroads were constructed which spanned the entirety of Cuba, with the assistance of at least $60 million (likely over $1 billion in today’s currency) in American investment. The Cuban Republic’s relatively well-developed transportation is credited with facilitating much of the Republic’s incredible progress in healthcare. The same article notes that the Cuban Republic was exceptional by Latin American standards due to its ability to provide “relatively easy access to fairly high-quality healthcare for an unusually large share of the population…,” due partly to the government’s investment in social services, and aided by the government's drastic improvement of sanitation as well as water and sewer infrastructure. Before the Revolution of 1959, Cuba’s infant mortality rate was only 33 per 1000, less than a third of the average for Latin America and functionally identical to that of Europe. Additionally, the ratio of medical personnel to population in the Cuban republic was 2.5 times greater than the average for the region and virtually identical to the European average. Life expectancy in the Cuban Republic was 64 years, a full 14 years greater than the average for Latin America, and just five years below that of the United States. The Cuban Republic was also notably dedicated to matters relating to education, and the Cuban constitution – in its various iterations – always provided for free and compulsory education. As a result of this dedication, in 1955, Cuba’s literacy rate was 79 percent, amongst the highest in Latin America. Taking into account Cuba’s significant rural population, largely unreachable by the government at that time (not an unusual problem for developing nations), these feats in medicine and education are truly remarkable.

Human rights

Finally, and most importantly, the Cuban Republic continually made impressive advancements in human rights and liberalization. In Cuba’s 1940 Constitution, widely considered a bulwark of freedom and social justice, Cuban delegates included language which provided for anti-discrimination protections and other liberal principles. Notably, the constitution included unparalleled protections for Cuban women. The United States had, prior to the end of its provisional occupation in 1902, re-imposed the Spanish Civil Code upon Cuba as a stop-gap alternative to the difficult process of drafting a new body of law for the island. The Spanish Civil Code was heavily Catholicized, and thus, held regressive and prohibitive views of women and their role in society. During the short period of its existence, the Cuban Republic made remarkable progress in removing the religious influences from its body of law, and in elevating the status of women in the Cuban society. In the early 20th century, Cuban women catapulted from a position in which the law afforded them little autonomy and no property rights, to being able to own property, vote, divorce their husbands, and organize politically. Laws were also passed which attempted to abolish all forms of discrimination based upon sex, although their implementation proved difficult.

Cuba’s contributions to the cause of human rights during the republican period were not limited to the Constitution of 1940, or to Cuban domestic pursuits; Cuba was essential to the progress of the international human rights movement. In the latter years of World War 2, Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt communed to discuss the post-war order, and to construct a world order amenable to their respective interests. The notions underpinning the United Nations, as an international organization dominated by the great powers and designed to serve as the arbiter of their new world order, emerged from these discussions. It was the efforts of various Latin American nations which made the United Nations what it is today: not just an organization designed for ensuring security and stability, but a dedicated, efficacious bastion of human rights. More specifically, it was Cuba’s delegation that assumed a leadership role of the Latin American bloc, at that time the largest group of nations in the original 58-state body, and spearheaded an aggressive charge to re-define the nature of the United Nations as a body primarily dedicated to the defense of human dignity. During the first session of the United Nations, the Cuban delegation became the first to submit a proposal that the United Nations consider issuing an authoritative statement demonstrating its commitment to human rights, a suggestion that ran counter to the immediate interests of the United States and other major members of the body. When the original motion failed the Cuban delegation resolved to pursue it with the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council which, due to the Republic of Cuba’s tenacity, established the Commission on Human Rights for the purpose of drafting an “international bill of rights.” Cuba also submitted a draft such declaration, which inspired the final document, serving as a model in both substance and form. If it were not for Cuba’s novel idea that universal human rights should be listed, so that they might be easily understood, attained, and defended by persons of every walk of life, the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights might never have come into existence. Throughout most of the modern era, outside of religious doctrine and certain areas of academia, rights were seldom discussed in the context of “humankind,” “international,” or “universal.” Rather, rights were seen as the prerogative of the nation-state and were outlined in national contexts or documents (e.g., state constitutions.) Cuban, and larger Latin American influence over the United Nations assisted in shifting that paradigm, and it is perhaps the most incredible part of the Cuban Republic’s legacy.

Conclusion

It is important that the presentation of these facts not be mistaken as an effort to obscure the serious shortcomings of the Cuban Republic. It is especially critical that the aforementioned economic statistics not be misused to obscure the gross income inequality under which a segment of the Cuban Republic’s poor languished, or to exonerate those responsible for the political instability which plagued the era. Rather, knowledge of this period is crucial for two major reasons. First, the Cuban regime often boasts about spectacular achievements (particularly in the fields of health care and literacy), and these “achievements” form a central pillar of revolution propaganda, but the above data illustrate that most of these regime “successes” were largely achieved by the Republic which came before. Second, and even more important, this story of the Cuban Republic is the story of a brave people who fought for countless years to achieve some measure of freedom and liberalism, only to have it snatched away from them by a revolution – and revolutionaries – steeped in perfidy. Unfortunately, irony abounds in present-day Cuba which, once a key drafter of the original document, now bans the distribution of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on the island and severely punished those in possession of the document. Additionally, while Fidel Castro was given the chance to defend himself in open court on July 26, 1953 – in front of relatively fair-minded judges and the press – those who live on the island in the present day are denied that right. While Castro was released from prison after organizing an amnesty campaign from his cell, having served less than 3 years of his 15-year sentence, Cubans are now subjected to draconian prison sentences in medieval prisons. Perhaps this is why many Cubans prefer to refer to the Republican period as “free Cuba,” drawing a powerful juxtaposition with present-day, “un-free Cuba.”

History has yet to absolve Fidel Castro, or the brutally oppressive regime that he left behind, but it seems to be in the process of absolving the principles of the Republic which Castro worked so hard to topple.

What do you think of pre-revolutionary Cuba? Let us know below.