Three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan was involved in one of the most important trials of the twentieth century. The Scopes Trial took place in 1925 and involved the age old debate between religion and science. Edward Vinski follows up on his first article on the trial (available here) and considers what William Jennings Bryan believed and when he believed it.

On the surface, William Jennings Bryan’s involvement in the famous State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes court case seems inconsistent with his earlier public life. Although he was long a supporter of progressive causes, Bryan’s prosecution of Scopes, a high school teacher who violated Tennessee’s statute against the teaching of non-Biblical Human Evolution, appears to represent an about-face: a harsh, conservative punctuation to the life of a man who famously backed women’s suffrage, prohibition and regulation of the railroads. Indeed, for those whose knowledge of Bryan comes only from the film or stage versions of Inherit the Wind, dramatizations that use the trial as a metaphor for McCarthyism, he appears to be an arch-conservative purveyor of hostility and fear. What is the truth about Bryan’s anti-evolution position? Were they long-held beliefs or did they reflect a growing conservatism in Bryan’s social ideas?

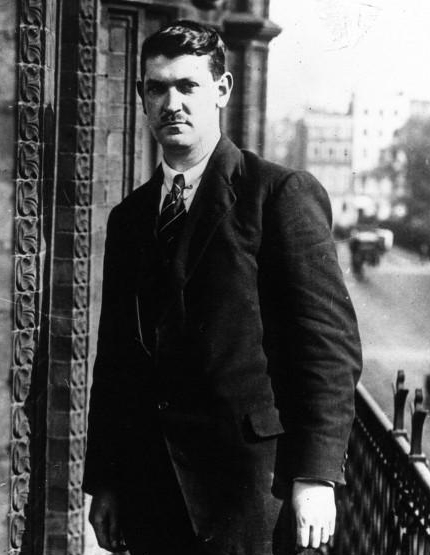

Who Was William Jennings Bryan?

Born in 1860, Bryan became one of America’s most influential political and social figures. His famous “Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 Democratic National Convention secured him that party’s presidential nomination. Despite his loss to William McKinley in the general election, Bryan would receive the Democratic nod two more times, losing to McKinley again in 1900 and to William Howard Taft in 1908. In spite of his pacifist leanings, he volunteered for duty in the Spanish American War, and although he never saw combat, he achieved the rank of Colonel in the Nebraska State Militia. Bryan was selected as President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, but resigned in 1915 over a disagreement with Wilson’s position following the Lusitania sinking. Still, he campaigned for Wilson’s re-election in 1916, and offered his services to the President following the United States’ entry into World War I. In the years following his work for Wilson, he was, among other things, a frequent speaker on the Chautauqua circuit, and a supporter of the progressive movements mentioned above.

A campaign poster for William Jennings Bryan in the 1900 presidential election.

In the film version of Inherit the Wind, The Bryan character[1] speaks in opposition to “godless science” and “agnostic scientists”. In fact, Frederick March, in his portrayal of the character goes so far as to pronounce “evolution” as “evil-ution” throughout the film. Bryan is portrayed as being a strict Biblical literalist who believed truly that Jonah was swallowed by a whale, that Joshua commanded the sun to stand still and in the accuracy of Bishop James Ussher’s estimates of the earth’s age. In fact, Bryan was excited by the potentialities of applied science. He went so far as to join the American Association for the Advancement of Science as a means of refuting the notion that he opposed scientific investigation. Bryan also accepted the possibility of non-human evolution, but he was worried that when science denied the supernatural, “every manner of immoral behavior” would be unleashed upon the world (Kazin, 2006, p. 273).

Two questions now arise. First, did Bryan’s opposition to evolution reflect a long-standing belief or a change to more conservative opinions in his later years? Second, to what degree was his attack on science inconsistent with his progressivism? To answer these questions, we will turn our attention to three sources: Bryan’s oft-repeated speech “The Prince of Peace”, his argument against scientific testimony during the Scopes Trial and his never-delivered closing speech that was included as a postscript in the trial transcript.

The Prince of Peace

One of the first clues to Bryan’s position on evolution comes from his 1904 speech “The Prince of Peace” (published in book form in 1909). In it, he stated that:

I have the right to assume, and I prefer to assume, a designer back of the design-a creator back of the creation… no matter how long you draw out the process of creation, so long as God stands back of it you cannot shake my faith in Jehovah… I do not carry the doctrine of evolution as far as some do; I am not yet convinced that man is a lineal descendant of the lower animal. I do not mean to find fault with you if you want to accept the theory…you shall not connect me with your family tree without more evidence than has yet been produced” (Bryan, 1909, p.12-13).

Fine. He seems willing to say “to each his own”. Yet years later, he would be at the fore of the anti-evolution movement in the United States. Was this a change of heart? Well, a closer examination of “The Prince of Peace” demonstrates that there was not necessarily a substantial change, for there is one easily overlooked passage a mere three pages earlier that sheds light on his fears. In describing why a system of morality based upon reason alone would be deficient, he stated:

As it rests upon argument rather than authority, the young are not in a position to accept or reject. Our laws do not permit a young man to dispose of real estate until he is twenty one…because his reason is not mature (Bryan, 1909, p.9).

Bryan’s concern for the moral life of young people would, in part, drive his anti-evolution crusade decades later. He feared their blind acceptance of materialistic arguments without a solid foundation of faith behind them. Shortly after this statement, he described his own youthful skepticism before concluding that “I have been glad ever since that I became a member of the church before I left for college, for it helped me during those trying days” (p. 11). The young person “is just coming into possession of his powers, and feels stronger than he ever feels afterwards-and he thinks he knows more than he ever does know” (p. 11). Thus, young people can become easily confused.

The Argument Against Expert Testimony

The second source for understanding William Jennings Bryan’s ideas comes from the Scopes Trial Transcript. On Thursday July 16, 1925, the focus of the trial turned to whether or not the testimony of scientists would be admitted into evidence. The defense hoped that these scientists would demonstrate that the study of evolution did not necessarily contradict the Biblical account of creation. In speaking against such testimony, Bryan turned to the tried and true position that had made him a three-time presidential nominee: the right of the populace or their elected representatives to regulate what is taught in US public schools.

“The statute,” he said, “defines exactly what the people of Tennessee desired and intended and did declare unlawful and it needs no interpretation” (Scopes Trial Transcript). The statute contained two provisions. It was illegal first “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Devine Creation of man as taught in the Bible” and second “to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals” (Tennessee House Bill 185). Bryan acknowledged that the testimony of experts would be acceptable if the statute only contained the provision relating to Biblical contradiction. By adding the provision about descent from lower animals, however, the legislature removed that possibility.

This is not the place to try to prove that the law ought never to have been passed…the people of this state passed this law, the people of this state knew what they were doing when they passed the law, and they knew the dangers of the doctrine-that they did not want it taught to their children (Scopes Trial Transcript).

It is not for nothing that he was called “The Great Commoner”. Long a champion of the working class and opponent of corporate power, he fought to protect the weak and poor from exploitation. “The rule of majority opinion against imposing elites” (Gould, 1999,p. 156) was long one of William Jennings Bryan’s primary focuses, and it is that point he tried to drive home in his attempt to block expert testimony.

Bryan’s Final Speech

A final source of Bryan’s views come from his proposed address following the trial. On the final day, the defense led by Clarence Darrow waived its right to closing argument and recommended that the jury return a verdict of guilty upon Scopes. In so doing, they not only set the stage for an appeal, but also deprived Bryan of his own closing remarks. Bryan’s speech was, however, appended to the trial transcript.

In the address, Bryan rehashed several of the points we have covered. Citing recent precedent, he pointed out the right of the state to control the public schools and to “forbid the teaching of anything ‘manifestly inimical to the public welfare’” (Scopes Trial Transcript). In addition, he claimed that the law was in no way an attempt to force religious beliefs upon the populace, but rather the majority’s attempt to protect its religious heritage from attacks by “an insolent minority…to force irreligion upon the children” (Scopes Trial Transcript). The statute, according to Bryan, did not represent a devaluation of science, and in fact Christians welcome truth wherever it may be found. This, in turn, led to his second point: that evolution is not truth but rather “millions of guesses strung together” and that “there is no more reason to believe that man descended from some inferior animal than…to believe that a stately mansion has descended from a small cottage” (Scopes Trial Transcript).

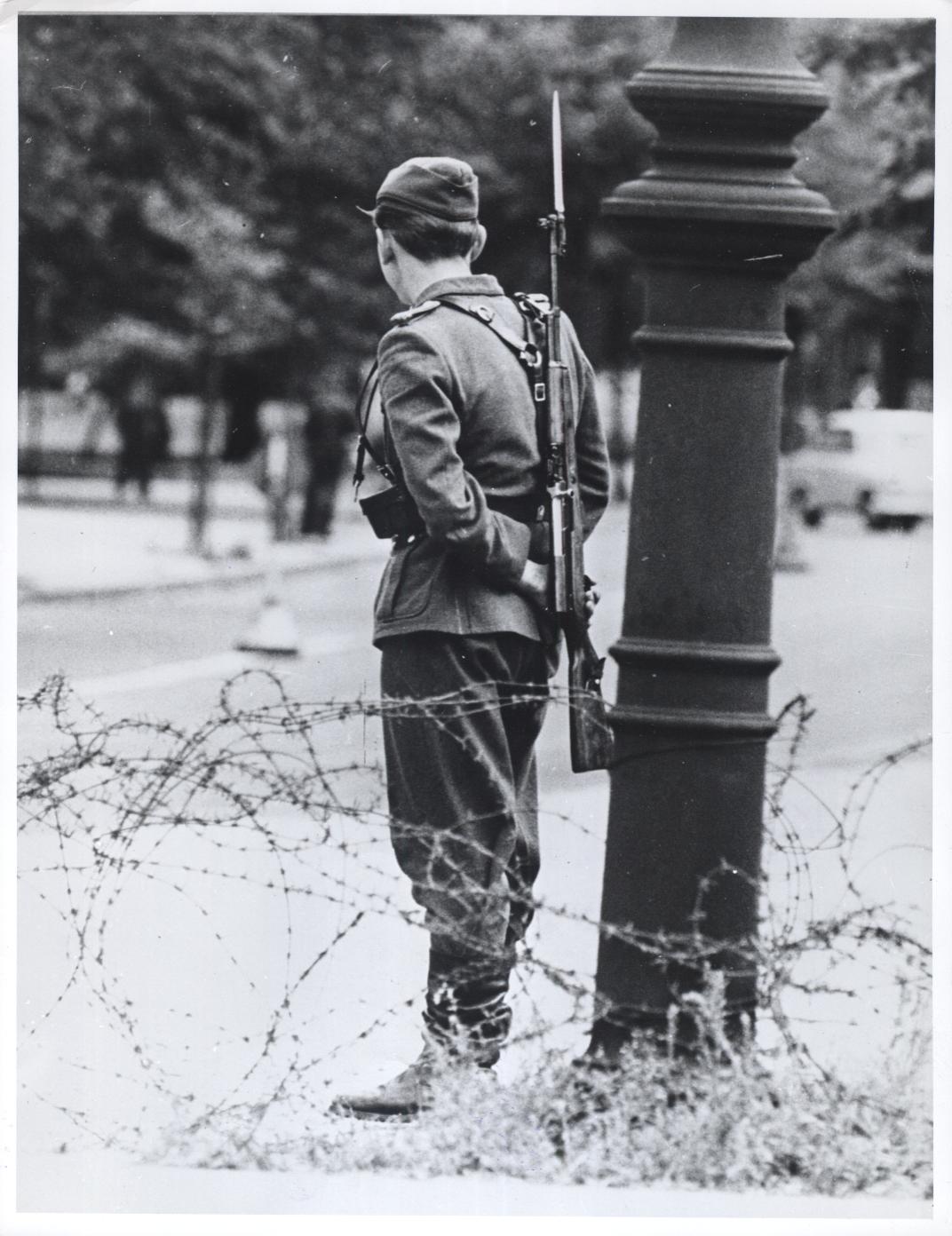

Toward the end of the address, however, Bryan describes Darwin’s “barbarous sentiment”. “Darwin,” he wrote, “speaks with approval of the savage custom of eliminating the weak so that only the strong will survive” (Scopes Trial Transcript). It was the Social Darwinism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that William Jennings Bryan most feared. He feared that under it, eugenics, euthanasia and sterilization would flourish as persons and nations tried to create a perfect race based upon the doctrine of survival of the fittest. From those perfect “supermen” world-dominating superstates would surely emerge. “Science,” he continued, “is a magnificent material force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine” (Scopes Trial Transcript). In Bryan’s mind, this was never more evident than in the First World War - not yet a decade in the past. “Science,” he wrote, “has made war more terrible than it ever was before. “The world needs a Savior more than it ever did before” and it is only “the meek and lowly Nazarene” who could save it (Scopes Trial Transcript). With that, Bryan returns full circle to “The Prince of Peace”.

Conclusion

It’s clear that Bryan’s involvement in the Scopes Trial did not represent a substantial deviation from his prior progressive tendencies. He was long concerned with the effect adults can have on the impressionable minds of the young, and he strove to protect the young from such influence. He championed the right of the people to determine their laws. Finally, he long believed that, left unchecked, science posed a great threat to humanity.

With hindsight, it is hard to argue with Bryan’s claims. One can only image his outrage at Nazi concentration camps, at US internment camps, and at bombs so powerful that they could destroy the world as we know it several times over. Bryan may have been wrong on a number of levels, not least of which is that scientific facts are not bound by majority opinion. But if he was wrong, he might well have been wrong for the right reasons.

Did you find this article interesting? If so, tell the world. Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

Edward J.Vinski, Ph.D is Associate Professor of Education at St. Joseph’s College, NY.

[1] Bryan’s name was changed to Matthew Harrison Brady for Inherit the Wind.

References

Bryan, W.J. (1909). The Prince of Peace. New York: Fleming H. Revel Company.

Gould, S.J. (1999). Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. New York: Ballantine Books.

Kazin, M. (2006). A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Anchor Books.

Scopes Trial Transcript, 1925 Tennessee House Bill, 185.