The concern with workplace health and safety and workers' rights has been discussed for decades. Throughout British history, there have been many attempts by workers, to create unofficial trade unions to improve their working situation. During the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the question of whether our working environments are safe, necessary and improve an individual’s productivity has been asked. The pandemic saw many people begin the transition into the work from home (WFH) structure as many offices and buildings could not cater to social distancing measures, efficient ventilation or isolate the spread of disease. Of course, many were unable to transition to a WFH strategy and had to continue to travel to their place of work. Organisations were faced with the challenge of managing the spread of disease, protecting workers from illness, and work productivity.

Health and safety in the workplace is not a new phenomenon brought about by the pandemic but one that is rooted in British history. Workers endured gruelling labour and toil with poor living and working conditions, with a lack of government reform to protect workers and their families from injury or even death. It was not until the Health and Safety at Work act of 1974 that was introduced to protect workers and their rights. Although throughout the nineteenth century, there was a gradual progression towards improving the working lives of many Victorians, for example, the Factory Act in 1833. This article explores how the living and working conditions of seamstresses in nineteenth-century west end London became pushed into public discussion and Parliament's reluctance to pass reforms to ease the lives of seamstresses.

Amy Chandler explains.

Seamstresses in 19th century France.

The distressed seamstress

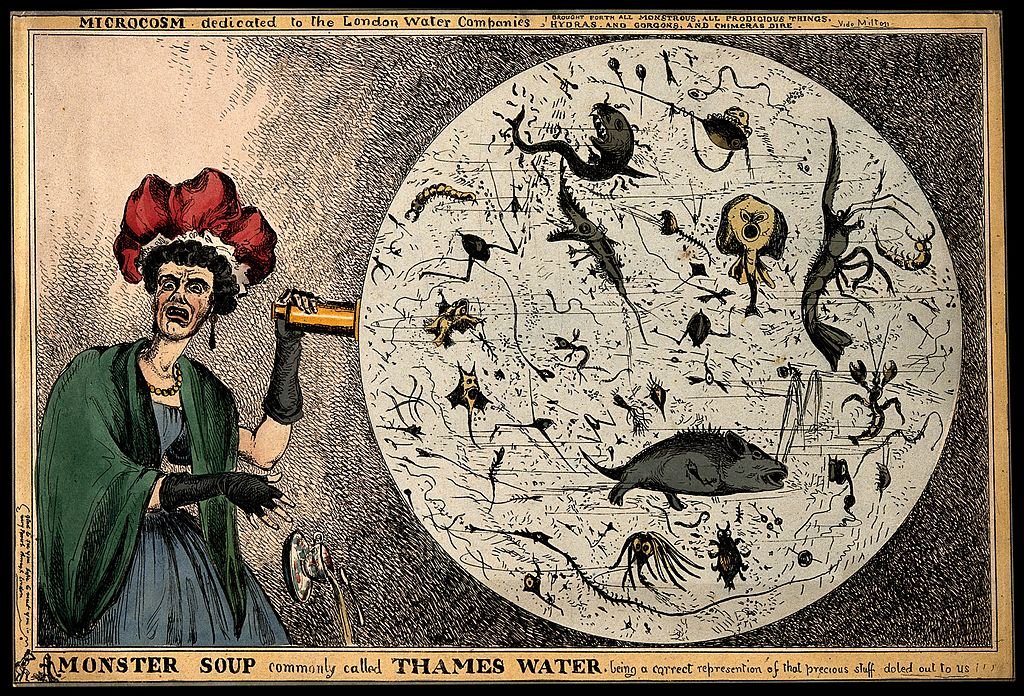

The industrial revolution took place between 1760 – 1840 and transformed the UK in many ways from the increased number of factories, trade, pollution, and a decline in living conditions. The industrial revolution also increased the chances of developing new illnesses from poor living conditions and lack of sanitation policies. London expanded rapidly and offered a new life for people in the city to find opportunities and employment, however the reality was bleak. Many found it hard to find work and earn enough money to stay in accommodation. Options were bleak, and many women resorted to prostitution or ended up in workhouses; some women were forced into prostitution to earn money on top of their daily employment. During the Victorian period, sewing was seen as a feminine quality and a skill taken up by women of all classes. The occupation of a seamstress was taken up mostly by working-class women and some upper-class women who were unable to become governesses, to support themselves and their families.

The image of the distressed seamstress became a cause celebre, which meant a controversial figure that attracted public attention and interest. The image of the distressed seamstress frequented art and literature in the nineteenth century with Thomas Hood’s famous poem Songs of the shirt 1843, depicting the plight of seamstresses as “fingers weary and worn, With eyelids heavy and red. A woman sat in unwomanly rags, plying her needle and thread”.(1) Hood’s poem continues throughout twelve stanzas revealing the plight of the living and working conditions of the life of a seamstress. Other literary figures attempted to shed light on the lives and hardships of the seamstress, such as Richard Redgrave. Hood’s poem inspired Redgrave to illustrate the figure of the seamstress as a pitiful and lonely figure with no escape to a better life or improved living and working conditions.

The death of seamstress Mary Walkley

In 1863 the course of how seamstresses were viewed changed forever after the death of a seamstress named Mary Walkley, “a workwoman in the employment of Madame Elise, described as Court Dressmaker, of 170, Regent Street”.(2) Women worked all day and night to complete orders, especially during London’s busy social season between April to June, when young women, often called debutantes, would attend social events in hopes of securing a marriage with a wealthy suitor.(3) After investigation, Walkley’s death was caused by “long hours of work and insufficient ventilation” and urgent calls for government officials to “establish by law regulation that might prevent the occurrence of such evils as this case brought to life”.(4)

Walkley's death in 1863 highlights the poor living and working conditions for seamstresses and is an example of what conditions women endured to survive in Victorian London. This particular case caused public outcry and awareness of the shocking conditions in the sweat industry, and there was no parliamentary legislation to change the situation, but public awareness and concern became apparent. Walkley’s case had a public inquest where Dr Lankester assessed the working and living environments. Lankester concluded the overcrowding and lack of ventilation for the number of workers in the space “open[s] up the whole question of the interior conditions of the workshops, workrooms, and sleeping rooms of the metropolitan workpeople”.(5) This situation also raised many questions regarding the “number of hours that persons may be employed in sedentary occupations in ill-ventilated rooms”.(6) Lankester’s report suggested the urgent need for parliamentary legislation to enforce sufficient ventilation and regulation of working hours, as “establishments like those of Madame Elise” were not uncommon throughout London.(7)

The death of Walkley and worker's rights for seamstresses were debated in great depth in the Houses of Commons, for example, Mr Dawson raised the humanitarian concern regarding their work. Dawson asked Parliament to consider if government officials “would give their support to a Bill for defining and limiting the hours of labor, and regulating and inspecting workrooms, alike in the interests of humanity as for the sake of sanitary precaution?”.(8) The debate of Thursday, 25 June 1863 also questioned: “why these establishments should not be placed under proper regulations” such as hours, registration and inspection that were mandatory law for places of employment such as factories, mines, and bakehouses.(9) This case never caused a change in legislation despite public outcry and dress shop owners who desired Parliamentary legislation to reform and recognise the hardship that many endured. Owners of dressmaker shops, like Madame Elise, did have some authority to make changes for their workers, but these were down to personal discretion. Many owners could not afford to regulate working hours as they could lose business to their competitors.

The working class had limited options in terms of choice of occupations due to socio-economic factors. Many workers ended up in the workhouse or following a life of prostitution to survive. Therefore, for working conditions to improve, the authority for change was in the hands of a handful of individuals who were hesitant to pass reforms. Despite there being no official legislation passed, the case of Walkley and the public debates surrounding her death did cause a shift in the public perception of seamstresses. Parliamentary transcripts are evidence of government officials' awareness of the significant difference in workers' rights, such as in factories. Parliament passed reforms to improve the health and safety of workers in factories, such as the Factory Acts of 1833, 1847 and 1850.

After Walkley’s death hit the press, there were questions from the public asking whether Madame Elise, as the owner, should be punished for her ill treatment of workers that contributed to Walkley’s death. This case highlighted a moral dilemma for many employers, as demonstrated by Parliament questions. Sir George Grey emphasised that “masters and mistresses, who are liable to provide for their apprentices food, clothing, and lodging, and have wilfully omitted to do so, are subject, upon conviction, in cases where there has been danger to life or permanent injury to health, to very severe punishment.”(10) Grey shifts the blame from the employee onto the employer for their negligence and ill-treatment of their workers.”(11)

Furthermore, the press reported the general public’s disgust of the working and living conditions.(12) One publication stated that the blame for Walkley’s death was Madame Elise and her debtors, such as duchesses and countesses, where workers were “overworked and poisoned” in Madame Elise’s establishment.(13) The report suggested that these debtors were “often answerable for moral privation and misery” by their “heedlessness and carelessness [… had] often been the cause of many weary hours night work to these poor girls”.(14) The blame was focused directly on the employers and the upper-class customers who placed the social season above public health. Arguably, the upper classes should have gained a conscience and concern for the establishments that they frequented. Madame Elise was unpunished for her negligence, but this situation questioned how workers were badly treated and unprotected by legislation that could ensure workers were protected from injury and death in a place of employment.

Calls for change

Public awareness of the seamstress industry continued to surge in 1906 with The Sweated Industries Exhibition organised by the Daily News. The exhibition aimed to “highlight ‘the evils of sweating’ ” and the public response and attendance were “unprecedented”.(15) The exhibition attempted to create awareness about the poor working and living conditions of seamstresses, whether they worked in a dressmaker’s shop or at home. This exhibition took place over forty years after the Walkley case and illustrates how slow progress for workers' rights, health and safety and reforms were during the nineteenth century. Much Parliamentary legislation and employment rights we are familiar with today took decades to reach the standard that protects workers from exploitation. Therefore, it took over forty years after the Walkley case for the plight of seamstresses to be taken seriously by Parliament and the general public with legislation achieved in 1909 with the establishment of the Trade Board Act that “introduced a legally enforceable minimum wage”.(16)

The Trade Board Act (later renamed the Wages Council in 1945) aimed to regulate the wages for workers in sweated industries such as seamstresses. Board members were representatives of the workers, such as trade unionists, representatives of the employers and government-appointed members. The council had an equal number of representatives from workers and employers and the government-appointed members were fewer.(17) The board proposed the minimum living wage and regularly adjusted the wage based on the state of trade and the cost of living.(18) However, there were ways for employers to avoid having to pay minimum wages through persuading the board that a worker was incapable of performing their expected work through gaining permits for workers with physical or psychological disabilities.(19) During a debate of the Trades Board Act 1909, the extent to which sweated industries suffered was revealed to Parliament. The debate highlighted that workers endured “excessive hours of labour and insanitary state of houses” and that “the earnings of the lowest classes of workers are barely sufficient to sustain existence”, resulting in “ceaseless toil, hard and often unhealthy” work.(20) The legislation proposed in this debate attempted to change working conditions and emphasise that the current wages were insufficient to sustain a healthy lifestyle. Despite this evidence exposing the exploitation of seamstresses, Parliament still were reluctant to pass bills that would even marginally improve the life of seamstresses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the life of a seamstress was slow to change, and legislation was well overdue, in comparison, to progressive change in working conditions for other occupations such as factories. The seamstress was integral to London’s social season and everyday life but was neglected by Parliamentary reform. The image of the distressed seamstress was not confined to the shadows in Victorian London but dragged into the public sphere where the general public attempted to change working and living conditions. In contemporary society, we have an ever-growing issue with the rise of fast fashion that exploits their workers in order to manufacture at a fast pace to ‘cash-in’ on popular catwalk trends.(21) In the same way that London’s social season exploited seamstresses to produce dresses to wear once and never again. Dress shop owners like Madame Elise used the social season as a way to ‘cash in’ on the hysteria of London’s social events and high demand for custom made gowns. The exploitation and high demand of popular trends mirrors the similar problems experienced in the Victorian era. Today, public awareness and the development of social consciousness have caused a shift in products becoming sustainable and ethically sourced to reduce the exploitation of workers overseas.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

Now read Amy’s article on the Great Stench in 19th century London here.

Bibliography

Crumbie, A. ‘What is fast fashion and why is it a problem?’, Ethical Consumer, 5 Oct 2021 < https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/fashion-clothing/what-fast-fashion-why-it-problem >.

Fleming, R. S. ‘ “Coming out” During the Early Victorian Era: about debutantes’, 9 May 2012, Kate Tattersall Adventures < http://www.katetattersall.com/coming-out-during-the-early-victorian-era-debutantes/ >.

Harris, B. ‘Gender Matters’, The Victorian Web, 10 Dec 2014 <https://victorianweb.org/gender/ugoretz1.html >.

HC Deb 23 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1316.

HC Deb 25 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1433.

HC Deb 25 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1434.

HC Deb 28 April 1909, vol 4, cols 343.

Hood, T. ‘Song of the shirt’, The Victorian Web, 16 December 1843 <https://victorianweb.org/authors/hood/shirt.html > .

Matthews, M. ‘Death at the Needle: The Tragedy of Victorian Seamstress Mary Walkley’, Mimi Matthews, 20 Sept 2016 <https://www.mimimatthews.com/2016/09/20/death-at-the-needle-the-tragedy-of-victorian-seamstress-mary-walkley/ >.

Sun. The Case of Mary Anne Walkley. The British Newspaper Archive (26 June 1863).

Warwick Library, ‘The Sweated Industries Exhibition, 1906’, Modern Records Centre, 15 Feb 2022 <https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/archives_online/digital/tradeboard/1906/>.

Warwick Library, ‘What were trade boards?’, Modern Records Centre, 15 Feb 2022 < https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/archives_online/digital/tradeboard/boards/ >.

Yorkshire Gazette, ‘The London Seamstress’, The British Newspaper Archive (27 June 1863).

Bibliography

1 T, Hood, ‘Song of the shirt’, The Victorian Web, 16 December 1843 <https://victorianweb.org/authors/hood/shirt.html > [accessed 26 April 2022].

2 HC Deb 23 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1316.

3 R. S, Fleming, ‘ “Coming out” During the Early Victorian Era: about debutantes’, 9 May 2012, Kate Tattersall Adventures < http://www.katetattersall.com/coming-out-during-the-early-victorian-era-debutantes/ > [accessed 2 May 2022].

4 Sun. The Case of Mary Anne Walkley. The British Newspaper Archive (26 June 1863).

5 Sun. The Case of Mary Anne Walkley. The British Newspaper Archive (26 June 1863).

6 Sun. The Case of Mary Anne Walkley. The British Newspaper Archive (26 June 1863).

7 Sun. The Case of Mary Anne Walkley. The British Newspaper Archive (26 June 1863).

8 HC Deb 25 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1433.

9 Ibid.

10 HC Deb 25 June 1863, vol 171, cols 1434.

11 Ibid

12 Yorkshire Gazette, ‘The London Seamstress’, The British Newspaper Archive (27 June 1863).

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

15 Warwick Library, ‘The Sweated Industries Exhibition, 1906’, Modern Records Centre, 15 Feb 2022 < https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/archives_online/digital/tradeboard/1906/>[ accessed 25 April 2022].

16 Ibid.

17 Warwick Library, ‘What were trade boards?’, Modern Records Centre, 15 Feb 2022 < https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/archives_online/digital/tradeboard/boards/ >[accessed 2 May 2022].

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 HC Deb 28 April 1909, vol 4, cols 343.

21 A, Crumbie. ‘What is fast fashion and why is it a problem?’, Ethical Consumer, 5 Oct 2021 < https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/fashion-clothing/what-fast-fashion-why-it-problem >[accessed 3 May 2021].