Strange New Worlds

Martin Luther King, Junior was, still is, and always shall be remembered and revered for the myriad roles and responsibilities he assumed during a life which was as astonishing for its historical and cultural impact as it was appalling for the barbaric manner in which it was often disturbed and ultimately terminated.

Among his assumed or accepted capacities were preacher, teacher and practitioner of nonviolent resistance, writer, agitator, community organizer, civil rights leader, Nobel Peace Prize winner. And Trekkie?

Even Nichelle Nichols, who played the groundbreaking part of Lieutenant Uhura - Communications Officer aboard the USS Enterprise on the short-lived but beloved original series of Star Trek - could hardly believe it. She would learn of Dr. King’s affinity for Gene Roddenberry’s visionary science fiction program when she found herself at a professional and existential crossroads, acting eventually upon-and revitalized by-personal counsel originating from a most unexpected source. Her peace-keeping mission was no longer relegated simply to the distant and abstract galaxies of Uhura’s 23rd century “where no man has gone before”, but in the very real here and now of the turbulent 1960s where Ms. Nichols could and would have a more direct, forceful, and noble influence.

To Boldly Go

Star Trek was not an easy sell. Having signed a development deal with Desilu Productions (started by, and named for, Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball) Gene Roddenberry submitted a proposal to executives at CBS for an episodic drama modeled after the popular western Wagon Train, transporting the consequent adventures from the American heartland to outer space. Though they were not necessarily contemptuous of science fiction as a genre with prime-time viewership potential, CBS did dismiss Star Trek as “too cerebral” in favor of the more sanitized and banal Lost in Space, a sort of interstellar Leave it to Beaver.

Roddenberry then pitched his concept to NBC which agreed to move forward after overhauling the show’s cast (Spock being the only character retained) due to the dismal reception of the pilot episode called The Cage. Unlike the creators of Lost in Space, Rodenberry was uninterested in formulaic, obtuse entertainment depicting a gentrified cast acting out pointless hijinks for the dubious benefit of injudicious audiences. Indeed, he was hell-bent on crafting an audaciously philosophical and tirelessly optimistic vision of the future which would be both brain-teasing and gut-checking, defiantly challenging racial prejudices, social constructs, and political xenophobia of the day.

“Gene was a man of ideas and ideals,” explains original cast member turned social media sensation George Takei. “Our human past may not have been all good, and neither had the history of his creation, Star Trek. But he had the boldness of spirit to go into a medium-television-famous for mediocrity and uplift it and succeed, against all odds, with idealism.”

To scratch the surface of what Takei describes as Roddenberry’s “world of infinite diversity in infinite combinations”, you need only examine a snapshot of the team gathered aboard the bridge of the Enterprise.

A Constellation of Rising Stars: Leonard Nimoy as Spock

Second in command and dogmatically contrary to the swashbuckling James Tiberius Kirk, whose heroics were almost always reactionary and emotion-driven, was Leonard Nimoy’s Mr. Spock, the ship’s Science Officer. His mother an Earth woman and his father Sarek a green-blooded Vulcan, Spock is denigrated as a “half-breed” by an android version of Kirk in the episode What Are Little Girls Made Of? Spock inherited not only Sarek’s pointed ears and perennially arched eyebrows but the predominant Vulcan trait of thinking and acting strictly within the logical boundaries of mathematics and science.

The wrestling match between sensible reason and deliberate speculation which the partly-human Spock must occasionally participate in is reminiscent (as is his physical appearance in a vague fashion) of Abraham Lincoln who grappled with similar ideological conflicts in his speechwriting, policy making, and personal thinking. What later turns out to be a carbon-based copy of Lincoln beams aboard the Enterprise in the Savage Curtain episode (third to last of the original series) and encounters Lt. Uhura to whom he refers as “an enchanting Negress”. Uhura takes no offense, assuring a properly chagrined ‘Lincoln’ that “in our century, we’ve learned not to fear words.” The replicated Emancipator replies, “The foolishness of my century had me apologizing where no offense was given.”

Nichelle Nichols as Uhura

The visually striking and multi-talented Nichelle Nichols had modeled, danced in Hugh Heffner’s Playboy Club, traveled extensively as a singer in the ensembles of Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton, and appeared variously onstage and onscreen. She was featured in Gene Roddenberry’s first series titled, appropriately for the soon-to-be Communications Officer of the Enterprise, The Lieutenant. Interestingly, because Uhura’s makeup swept her hair atop her head and accentuated Nichols’ naturally almond-shaped eyes, she was often mistaken for Asian by people viewing the program on black and white television sets.

George Takei as Sulu

The role of Helmsman Hikaru Sulu was filled by George Takei, who was very involved in several early plot lines alongside the show’s central triumvirate of Kirk, Spock and Leonard ‘Bones’ McCoy (“Dammit, Jim, I’m a doctor…”) played memorably by DeForest Kelley. Born Hosato Takei in Los Angeles to Japanese parents, he (at the age of four) and his family were rounded up along with more than 120,000 other Japanese Americans in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack and interred for five years in a perpetual state of “chaos and confusion” among “rows upon rows of black tar paper-covered Army barracks aligned in military parade precision”, first in Alabama’s Rohwer Relocation Center then Camp Tule Lake back in California.

Prior to navigating the Enterprise out of a succession of hazardous situations among the stars, one of Takei’s first film appearances was an uncredited role as the Japanese steerer who pulverizes Lt. John F. Kennedy’s torpedo boat in PT-109.

Walter Koenig as Chekov

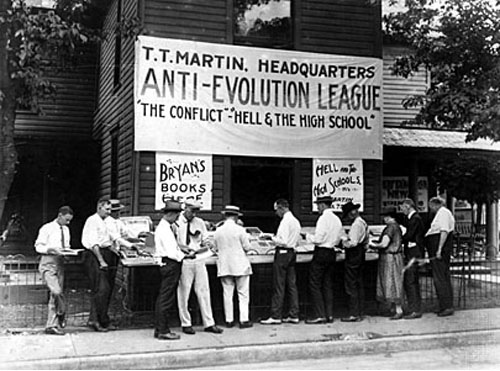

Takei’s prolonged absence while filming The Green Berets opposite John Wayne was responsible for the increased screen time given to Walter Koenig, introduced as Ensign Pavel Chekov in Star Trek’s second season. His parents, Isadore and Sarah Koningsberg, were Russian Jews who fled Lithuania for Chicago and ultimately New York where Isadore, a former Communist, found himself subject to scrutiny beneath the red-tinted lens of Joseph McCarthy’s un-American activities microscope. Koenig compared the McCarthy witch-hunts of the 1940s and 50s to “our version of the Spanish Inquisition or Robespierre’s Committee on Public Safety or the shadow councils of South American dictatorships.”

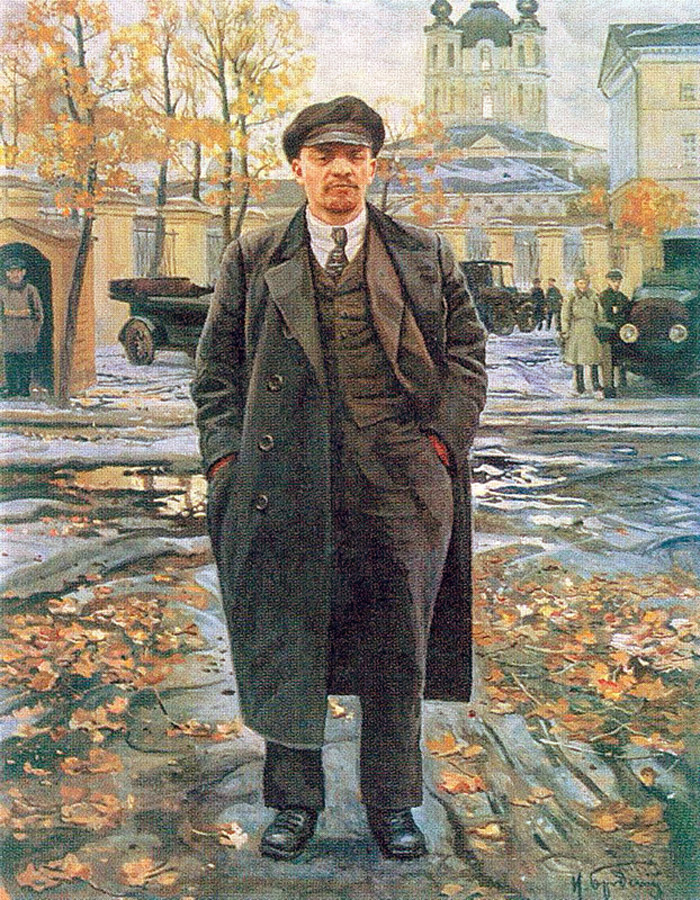

Roddenberry’s addition of a Russian to the cast was a further controversial brushstroke of brilliant multiplicity just as the successful missions of Sputnik and Vostok had given the Soviets the lead in the jingoistic space race, throwing further fuel onto the fire of the still-simmering Cold War. Beyond giving the prematurely balding actor a mop-topped toupee, drawing favorable comparisons among female Trekkers with Davey Jones of the Monkees, and requesting that Koenig over-enunciate an already cartoonish Russian accent (such as swapping W’s for V’s), Roddenberry’s public relations department concocted another puzzling fabrication.

The character of Chekov, according to a press release which was every bit a work of fiction as Star Trek itself, was created to satisfy the call for a Russian cast member proposed by the Soviet newspaper Pravda, a publication which pre-dated the October Revolution but had enjoyed its most immense readership under Lenin’s rule along with the Bolsheviks’ other propaganda sheet of choice Izvestia.

James Doohan as Scotty

James Doohan confessed that he was Canadian with “some Scottish blood in me, but that’s three hundred years ago.” He recalled being asked by Gene Roddenberry during his audition to judge for himself“which of the eight different accents I’ve just done for him would best fit the role of the Chief Engineer. It had better be a Scotsman,” Doohan decided. “They’ve built all the great ships around the world. The Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, the Titanic…”

That last example notwithstanding, the Enterprise’s Transporter Engineer adopted the guise of Montgomery Scott, still associated today with the catchphrase “Beam me up, Scotty”. Like “Play it again, Sam”, it is one of those peculiar anomalies of the pop-culture lexicon for having never actually been spoken as quoted. Much to Doohan’s regret, the aforementioned Lincoln-related episode Savage Curtain would be the only opportunity for Scotty to don the traditional Scottish kilt.

MLK Rescues Uhura

Star Trek did not become the mainstream cultural phenomenon that it remains today until after its 1969 cancelation and subsequent network syndication in the 70s. The series suffered, during its inaugural season, from lukewarm critical reaction and poor viewership ratings. It was also nearly altered drastically and for the worse by the potential departure of one of its major cast members.

Nichelle Nichols was routinely given a difficult time by certain security guards on the Paramount lot who pretended not to recognize the unmistakable actress with the intention of denying her access to the show’s soundstage. One afternoon, she was approached covertly by two mailroom employees who apologized for withholding the bulk of her voluminous fan correspondence - which rivaled that of either Leonard Nimoy or William Shatner - at the request of their supervisor who himself was acting on orders handed down from above.

Worse still, she was verbally accosted by a Desilu executive who told her in no uncertain terms following a first-season cast reduction that “If anyone was let go, it should have been you, not Grace Lee,” referring to Grace Lee Whitney who had played Captain Kirk’s personal assistant and hopeful love interest Yeoman Janice Rand until her role was deemed redundant. “Ten of you could never equal one blue-eyed blonde,” was his bigoted analysis.

These events proved the breaking point of the frustration already weighing heavily upon her at being little more than a prop on the ship’s bridge (with the notable exception of getting to sing in two early episodes), exhibiting her shapely legs in a red mini-dress and interminably intoning the line, “Hailing frequencies open, sir.” The last episode of the season having wrapped, Nichelle went to Gene Roddenberry’s office and tendered her resignation, effective immediately.

She attended an NAACP fundraiser the following evening where a fellow guest asked if she could take some time to meet with a big fan. Anticipating a short cordial chat followed by an autograph request or photo opportunity, Nichols was astounded to turn and stand face to face with Martin Luther King, Junior. “Yes, I am that fan,” King beamed, “and I wanted to tell you how important your role is.” He revealed to her that Star Trek was the only television show that he and Coretta allowed the children to stay up late and watch as a family and was completely taken aback by Nichele’s revelation that she was departing the program.

“You cannot and must not,” demanded King. “You have opened a door which must not be allowed to close. You have created a character of dignity and grace and beauty and intelligence. For the first time, people see us as we should be seen, as equals, as intelligent people, as we should be. Remember, you are not important there in spite of your color. You are important there because of your color. This is what Gene Roddenberry has given us.”

Nichols returned to Roddenberry on Monday morning to relay Dr. King’s message and retract her resignation. “God bless that man,” Gene said while fighting back tears. “At least someone sees what I’m trying to achieve.”

The Kiss

Before the series wound down to its fateful and unfortunate third season conclusion, it would shock the world with a provocative episode titled Plato’s Stepchildren. It begins in a manner not dissimilar from The Squire of Gothos (wherein Uhura is identified by the French-obsessed alien presence Trelane as “a Nubian prize”) as a landing party consisting of the crew’s principal players is manipulated for the amusement of their nefarious hosts. Here, a Utopian society has been founded on the planet Platonia by its leader Parmen based on the teachings of the ancient Greeks, namely Plato and Socrates.

Lt. Uhura and Nurse Chapel (Roddenberry’s wife Majel) are involuntarily beamed down to Platonia for inclusion in a stage play-equal parts dramatic, romantic, and sadistic-along with Kirk and Spock, all in Greek costume and under the influence of Parmen’s psycho-kinetic control. After Spock and Nurse Chapel have already done so, Kirk and Uhura have no choice but to comply with Parmen’s wish to see them kiss. This is commonly and mistakenly referred to as television’s first inter-racial kiss but the truth of the matter is that the British soap opera Emergency Ward 10 beat Star Trek to the lip-smacking punch four years earlier.

Furthermore, the sequence, as aired, features the second alternate take shot at the insistence of Paramount executives where Shatner pulls a struggling Nichols toward him and their lips do not make direct contact. This measure was taken to placate southern network affiliates who threatened to black out the entire hour based solely on the presentation of ‘the kiss’.

“And even when we shot this compromised version of the scene, I can clearly recall the network suits standing on the set watching us intently,” remembers William Shatner, “making sure that before the two of us performed our simulated kiss, we fought against it intently, making it absolutely clear that in the case of Kirk and Uhura, this was an ‘against their will’ coupling. Completely devoid of any passion, romance, or sexuality.” Nichelle Nichols raged that “It was bullshit! Bullshit! It was simply and clearly racism standing in the door…in suits. Strange how a twenty-third century space opera could be so mired in antiquated hang-ups.”

Regardless, it was a mountain-moving moment in American television and one can only imagine that writer Meyer Dolinsky anticipated the furor this scene would arouse when he scripted the lines of dialogue beginning with Uhura saying, “I’m so frightened, Captain. I’m so very frightened.”

“That’s the way they want you to feel,” Kirk reassures her. “It makes them think that they’re alive.” Uhura then declares affirmatively and defiantly that “I’m thinking of all the times on the Enterprise when I was scared to death…and now they’re making me tremble. But I’m not afraid. I am not afraid.”

Down to Earth and Back to Space

Many cast members happily accepted the challenge to “seek out new life and new civilizations” after they had shed their Starfleet insignia, tri-corders, communicators, and phasers (set to stun, of course).

Nichelle Nichols would use her sci-fi credibility to recruit engineers and astronauts for NASA, specifically appealing to females and minorities. Augmenting the encouragement she had received from Martin Luther King back in 1966, she would be further touched by the words of Whoopi Goldberg who would appear as Guinan on the last four seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Whoopi excitedly conveyed the story to Nichelle of how she had turned on the television as a child and seen Uhura featured prominently on the bridge of the Enterprise, screaming to her mother, “Come quick! Come quick! There’s a black lady on tv and she ain’t no maid.”

Leonard Nimoy campaigned for the dovish Eugene McCarthy and worked on behalf of the ACLU, Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers, and Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. One of the songs that appeared on Nimoy’s 1974 double-LP Outer Space/Inner Mind was a track entitled Abraham, Martin, and John, a musical tribute to Lincoln, King, John and Bobby Kennedy.

George Takei, an openly gay man with a decidedly wicked sense of humor, proudly uses his frequent appearances on the Howard Stern Show as well as his various social media platforms to advocate for LGBT rights and same-sex marriage legislation along with his husband Brad. The hit musical Allegiance, starring Takei and based on his experiences in the Japanese internment camps, opened at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego and has played to great acclaim in several major cities with a recent run at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre.

Suffering terribly from a hellish combination of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and pulmonary disease, James Doohan was honored shortly before his 2005 death with a convention called Beam Me Up One Last Time, Scotty. The keynote speaker was Neil Armstrong who made a rare public appearance to express his gratitude for the inspiration that Star Trek had given him in his quest toward the moon. “I want a Chief Engineer like Montgomery Scott,” Armstrong mused on a hypothetical return to the stars, “because I know Scotty will get the job done and do it right. Even if I often hear him say, ‘But, Captain, I dinna have enough time!’ So, from one old engineer to another, thanks Scotty.” Doohan was cremated after passing away, his ashes successfully beamed up into near-earth orbit in 2012-after two previously failed attempts-aboard the Falcon 9 rocket.

Live Long and Prosper!

Did you find the article interesting? Let us know why below…