Imagine this: two brothers are prisoners shackled in a cell in 1947. Now, they are free, and chains are broken. However, instead of enjoying their freedom, they are practically fighting each other to the death! This is the case for partition between India and Pakistan.

Prior to the independence of both nations in 1947, the fight for self-determination dominated the minds of the inhabitants within the Subcontinent. Possibly, the independence of both countries is the most defining moment for both since their freedom. Manifest in conflicts such as that in Kashmir, as well as the most recent major war known as the Bangladeshi Liberation War of 1971, the effects of partition are clearly still felt to this day. Not only did self-determination shape the future of those residing in the Subcontinent, but it also struck a huge blow to British prestige. Many speak of the partition and its consequences; however, many also do not fully grasp the events which led to the partition. From Gandhi’s Quit India movement in 1942, to Direct Action Day in 1946, I will shed light on key events which occurred shortly before Indian and Pakistani independence. I believe these events were the most pivotal in shaping how the partition played out.

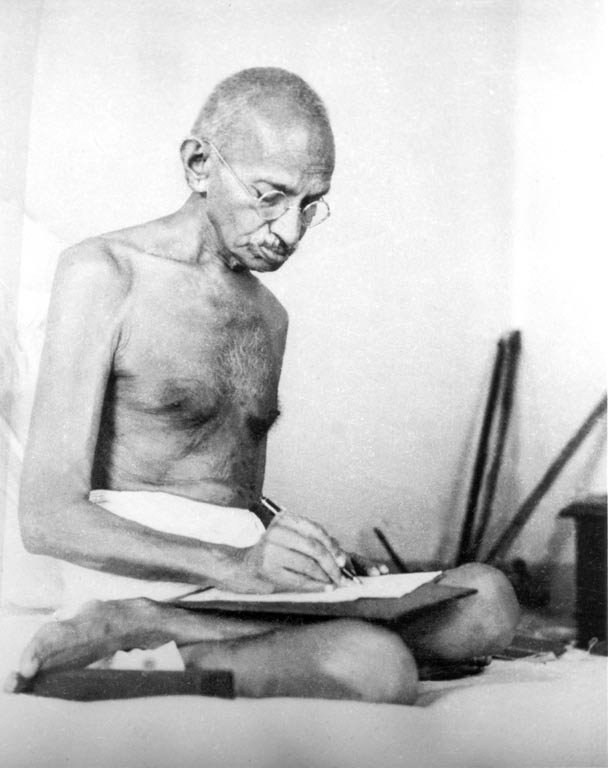

Quit India Movement and the Cripps Mission, 1942

Before the climax of the Second World War in 1945, Indian demands for independence were very much in full swing. In a meeting with Congress in 1942, Gandhi instructed other Indian leaders that it was the perfect time to seize power.He demanded that Britain departs from India and grants independence to the country. Congress would then agree on a peaceful mass movement and passed the “Quit India Resolution”, thus giving birth to the Quit India movement.[1]This was done in response to a failed mission by Sir Stafford Cripps, the British Chancellor at the time. Within the same year, Cripps was sent by Churchill to make terms with the Indian Congress. He offered that if India gives full support for the war effort, Britain will grant India complete independence once the war concluded. Congress overestimated British desperation in the war and rejected. They countered with the demand that India gains instant independence, which Churchill and Lord Linlithgow would not grant.[2] The Cripps mission completely broke down, and this event shows how stern Congress was in demanding immediate independence. By this point, the Indian people were exhausted, and had enough of fighting in the war for the British. This sentiment only intensified when the Japanese were gaining traction during their Southeast Asian conquests and were beginning to encroach on Burma.

Furthermore, Gandhi’s arrest by British authorities increased dissent within the population of the Subcontinent. Particularly in regions such as Bengal, there was a significant upsurge in anti-British sentiment within the rural areas especially. The Quit India Movement of 1942 has been compared by historians to the Great Revolt of 1857 in terms of sheer scale.[3] The arrest of Gandhi and other Congress leaders had also given the more extreme nationalists less restraint. Bolstering their confidence, a violent offensive was launched in what is known as the ‘August Revolution’. Telephone wires were cut, train rails were destroyed, police stations were stormed, and Congress flags were planted on key government offices. Multiple districts were seized and were occupied by the nationalist rebels. An ever-increasing number of peasants had also joined the fray, and uproar against British rule was surging. The government was rapidly losing control of the situation. However, the allies were gaining traction in the war against Japan, and the revolution gradually dwindled up until the end of August.[4]

Failure of the Simla Conference, 1945

Transitioning over to June 1945, the Simla conference was another example of the British failure to maintain their authority over India, and a contributor to their eventual departure. Viceroy Lord Wavell was eager to solve India’s communal and political problems due to World War Two almost concluding. He wanted representatives of India to agree on a national government to resolve disputes particularly between Jinnah’s Muslim League and the Congress. Yet another example of British failure in India, the conference proved unsuccessful. Jinnah had demands for nominations exclusively for members of the Muslim League as ministers. However, when Wavell tried to create a government, himself mainly consisting of Muslim league members, Jinnah rejected this proposal. In response, Wavell created the ‘Breakdown Plan’ which threatened to restrict Pakistan just to Punjab and the Bengal. However, British policy regarding India was indecisive and unclear seeing as Clement Atlee was unhappy with Wavell’s proposals in the Simla conference. He sent a cabinet mission to remedy the situation in India, but due to the unclear decision from Britain’s end, the conference negotiations broke down.[5] The rejection from Jinnah shows that political leaders in India were less willing to entertain British proposals, and aimed to manifest their own ideas of how an independent India should be structured. Therefore, it is evident that increased movements toward independence contributed toward British decolonisation between 1945 and 1970, especially in context of Indian independence.

Increase of Communal Violence: Direct Action Day, 1946

Additionally, the sheer intensity of communal violence within British India had escalated, adding pressure on the British government to decide regarding partition. Under the leadership of Ali Jinnah, the Muslim League called for the ‘Direct Action Day’ in August 1946. Initially meant to be a peaceful demonstration to affirm the demand for a separate Muslim state, it transformed into a massacre in Calcutta in the form of looting, arson and fighting between Muslim and Hindu mobs. Many ordinary people going about their daily lives were killed, beaten, or robbed. This solidified the idea that Muslims and Hindus cannot possibly co-exist in a single state, and potentially unintentionally aided Jinnah’s efforts to create Pakistan. It was a prelude to the partition massacres that would unfold later.[6] Overall, the increase in communal hostility between Muslims and Hindus highlighted Britain’s inability to control the situation in India. It was clear that Britain had been losing authority as was manifested through its ineffective response to the killings.

Mountbatten Plan and Partition, 1947

By 1947, tensions had reached an absolute boiling point. Major cities in Punjab were practically on fire. Gangs walked the streets of various major cities in the region and continuously fired weapons, threw rocks, and set shops on fire. In Bombay, Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh communities became increasingly paranoid regarding approaching each other’s ‘zones’, even when there was a delay in episodic stabbings. Most families had to acquire basic arms and barricade their houses to protect themselves from the raging violence. On the political scale, Jinnah and the Muslim League were still vocal about their demands for a separate state for Muslims, known as Pakistan. Louis Mountbatten was sent to India as the next and final Viceroy to attempt a partition plan.[7] The British administration could barely manage the Indian political situation at the time, and Clement Atlee (Who was then the Prime Minister) famously remarked that British rule would end there “a date not later than June 1948”. Considered to be the champion of Muslim minority rights in India, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was renowned for demanding extra political rights for the Muslims. Hence, this would evolve into a demand for an entirely new state.[8] Mountbatten knew that partition had to occur, as by this point, the idea that Muslims and Hindus could co-exist in one state had long been thrown out due to the sheer intensity of communal violence. Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer who had never even visited India, was commissioned with the arduous task of drawing the borders between India and Pakistan. This was to be done purely on religious grounds.[9]Once this was done on August 17, 1947 (two days after the independence of both countries), a massive diaspora would occur. Many refugees and locals would struggle due to this change, and they had to take the perilous journey of migrating to a completely new homeland based on their faith.[10] Thus, the modern states of India and Pakistan were born through bloodshed, diaspora and political turmoil.

Do you want to read more history articles? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

[1] Boissoneault, Lorraine. “The Speech That Brought India to the Brink of Independence”. Smithsonian Magazine. 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/speech-brought-india-brink-independence-180964366/

[2] McLeod, John. “The History of India. Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations.” (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group: 2002.) p 122

[3] Chatterjee, Pranab Kumar. “QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT OF 1942 AND THE NATURE OF URBAN RESPONSE IN BENGAL.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 43, 1982: 687–94. pp 687-688

[4] Kulke, Hermann and Dietmar Rothermund. “A History of India.” Sixth edition. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: 2016). p 251.

[5] Kulke, Hermann and Dietmar Rothermund. “A History of India.” Sixth edition. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: 2016). pp 256-257

[6] Khan, Yasmin. “The Great Partition: the making of India and Pakistan”. New edition. (New Haven; London, Yale University Press: 2017). pp 63-66

[7] Khan, Yasmin. “The Great Partition: the making of India and Pakistan”. New edition. (New Haven; London, Yale University Press: 2017). pp 83-87

[8] Philips, Sean. “Why was British India Partitioned in 1947? Considering the role of Muhammad Ali Jinnah” University of Oxford. https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/why-was-british-india-partitioned-in-1947-considering-the-role-of-muhammad-ali-0

[9] Menon, Jisha. “The Performance of Nationalism : India, Pakistan, and the Memory of Partition”. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). p 29

[10] Singh, Amritjit, Iyer, Nalini, and Gairola, Rahul K., editors. “Revisiting India's Partition : New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics.” (Blue Ridge Summit: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, 2016). pp 165-166