Russian history has been beset with a number of seismic changes. Here, Daniel McEwen considers four key ‘resets’ in Russian history – the start of the Romanov dynasty, two early 20th century revolutions, and the end of the Cold War.

Vladimir Lenin, a beneficiary of one of Russia’s ‘resets’. A 1920 depiction by artist Isaak Brodsky.

“Reset” was the buzzword on speakers’ lips this past January during [an online version of] the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In words as lofty as the Alps in the background, Klaus Schwab, the event’s impassioned founder hailed the Covid pandemic as “a rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, re-imagine, and reset our world."

Ironically, his idea was swept overboard by Covid’s next wave and hasn’t returned, perhaps because its advocates have since checked their history books. Resets have a chequered track record at best, with the 1789 French Revolution revered as the most notable, the Russian Revolution as the most execrable. And it was only one of that country’s four attempts to exploit a “rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, re-imagine, and reset their world ". Their failure explains why journalist Vladimir Pozner arguing Russia has never really been a democracy.

Reset #1 - 1613

Ivan the Terrible is dead. One third of the fledgling nation’s population has been wiped out in the internecine warfare known as “The Time of Troubles”. Weak and leaderless, the country is beset by enemies on all borders. Desperate to end the violence, the Zemsky Sobor, an assembly of the realm’s elites, gather to reset their system of governance.

This was a mountaintop moment in the country’s history, never to be repeated; a singular chance for Russians to shrug off the yoke of autocracy and rule themselves. But not one of the gathered could spell democracy let alone run one. Self-rule sounded like a lot of work. Had Fyodor Dostoevsky lived then, no doubt he would have been heard telling his countrymen that: “to go wrong in one's own way is better than to go right in someone else's.” Not that anyone would have listened. Instead of a reset, they rebooted the old system.

Historian Abraham Pailtsyn listened in on this assembly and was struck by what he didn’t hear – there was nobody speaking up for running the country for the people. Easier to just hand things over to the Romanov clan, the least objectionable of several candidates for the job. It was led by a 16 year-old teenager. His first official act was to hang a rival for the throne and his eight-year-old son, setting the tone for the next three hundred years.

Pailtsyn blamed this fateful lethargy on a deep national apathy.

Indeed it was. The appalling inhumanity of serfdom under the Romanov’s thumb approached can be compared to slavery. Nine tenths of the population lived in squalor, worked like beasts of burden to generate the unconscionable wealth enjoyed by the other one tenth. Little wonder the largest country in the world could do no better than a GDP barely equal to Spain’s! Quaintly embarrassing at first, this state-sponsored feudalism threatened the empire’s very survival when the forces of technological, social and political change began shifting the tectonic plates of world power.

Had it been the best of times, czarist Russia would still have needed Paladins of Enlightenment to guide it along the perilous path to modernization. But it was the worst of times - disingenuous czars, amply aided and abetted by motley crews of corrupt cabinet ministers, sadistic secret police and a supine nobility used brutality and repression to manipulate modernization to their exclusive benefit.

Typical of their tactics was the subverting of the abolition of serfdom, often depicted as the country’s ‘Great Leap Forward‘ to social and economic modernity. Some leap. Russia’s Emancipation Act of 1860 improved the quality of life for serfs about as much as the American Emancipation Act three years later improved the quality of life of slaves there. The czar and his minions retroactively limited, diluted and prolonged their people’s emancipation. At least freed American slaves did not have to pay compensation to their owners for the loss of their labor as was required of Russian serfs. In the end, emancipation offered the overwhelming majority of Russians basically two career options: over-worked, underpaid farmer or over-worked, underpaid factory worker.

Reset #2 - 1905

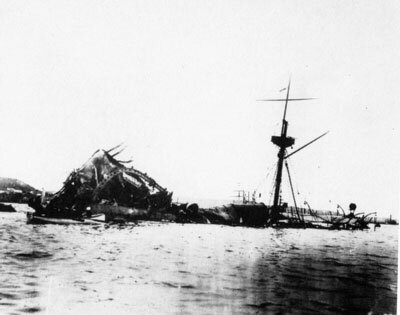

Still considered by many to be the ‘real’ Russian Revolution, this aborted reset was the high-water mark of Romanov duplicity. Japan had sent Czar Nicholas’ grand vision of a Pacific Empire to the bottom of Tsushima Bay in a naval defeat so shameful it nearly cost him his throne. Humiliated, he was forced to agree to a constitutional monarchy. Bells rang throughout the kingdom, people partied in the streets, and newspaper editors rhapsodized about the dawning on a new age of freedom.

All the man had to do was keep his word and he, his family and some hundred million Russians would have lived happily ever after, never having heard of Vladimir Lenin. But always more a ruler than a leader, Nicholas stayed true to his family colors and cravenly reneged on the deal, dismissing the reformers behind it as deluded dreamers. Egged on by a witless wife in the thrall of a charlatan monk, Nicholas all but dedicated the last twelve years of his reign to giving those dreamers even more reasons to want to him gone – dead or alive!

Reset #3 - 1917

Three years into World War One, two million Russian soldiers are dead and five times that number of peasants have died of starvation or disease. Millions more face the same fate, caught between the scorched earth policy of their own retreating soldiers and the pillaging by the advancing German troops. In the cities, people are starving to death, if they don’t freeze first, awaiting trains of wheat that rarely arrive. Ever bereft of empathy or wisdom, Nicholas felt not the slightest obligation to feed his own people, breaking their three-hundred year near-religious faith in the Czar as an all-knowing, all-caring ‘Little Father’. Not surprisingly, none of them felt the slightest obligation to save him when mutinous troops stopped his train. He went without a whimper. The bang was still to come.

Free at last of their Romanov masters, there was none of the apathy of 1613 and no going back like in 1905. This time rank and file Russians knew exactly what they wanted: participation in power, a fairer share of the nation’s wealth and no more czars! Unlike 1613, this time there was lots of talk. And talk. And talk. And so enters a man author/historian Edward Crankshaw described as “one more bacillus let loose to spread infection in a tottering and exhausted Russia.”

How Russians ended up with Vladimir Lenin and the tyrannical czars of Bolshevism is a question a library of books have attempted to answer. The most charitable explanation seems to be that a destitute, disillusioned people were simply too cold and too hungry to read the fine print on their deal with the Devil.

However it happened, Vladimir Lenin played a ghastly game of bait-and-switch, promising ‘Peace, Bread, Land’, but delivering war, terror and death. For this unwitting lapse of judgment, another ten million citizens would perish in the civil war that followed World War One. Its hapless survivors were condemned to seventy years in the gulag of Soviet-style socialism, notorious for short trials and long bread lines. Tellingly, the USSR’s GDP did not rise above a third that of arch-rival America’s.

Reset #4 - 1991

The catastrophic Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 opened Russians’ eyes to the true magnitude of the corruption and incompetence inherent in the Soviet system. Profoundly shocked, they began publicly questioning their leaders’ fitness for office. Five years later the Berlin Wall fell, burying Leninism in the rubble. At that time, per capita GDP was $23,000 in the United States, $16,000 in Western Europe and $6,800 in the rapidly dissolving ‘workers’ paradise’.

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved on December 26, 1991 but much to their dismay, the long-suffering proletariat were no sooner free of the iron grip of communism than Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to shackle them to unregulated capitalism – and barely escaped with his life for his trouble! When the dust of Glasnost had settled, Vladimir Putin and his oligarch friends had installed themselves in the Kremlin. While he labors mightily to restore the nation to a dubious former glory, its inglorious GDP has now shrunk to one-fifteenth that of United States.

What’s next?

Speculation about when and how Reset #5 will occur keeps pundits’ tongues wagging. Incredibly, the notion persists that Russians actually like strongman rulers. No one likes being bullied, surely the Russians least of all.

What do you think of Russia’s ‘resets’? Let us know below.